The mysterious and extinct Dacian language, lost by the 4th-6th century AD, has been "artificially resurrected" through the cinematic vampire Count Orlok: The Paleo-Balkan linguistic heritage in Robert Eggers' Nosferatu.

In the realm of cinematic artistry, few directors rival Robert Eggers when it comes to meticulous historical accuracy and atmospheric depth. His 2024 remake of Nosferatu, a reimagining of the 1922 German Expressionist classic, exemplifies this ethos. Eggers not only revived Count Orlok, the grotesque and enigmatic vampire, but also resurrected a dead language for his undead protagonist, Dacian.

This linguistic choice, while subtle, underpins the eerie authenticity of the film. Dacian, an ancient Indo-European language once spoken by the inhabitants of the Carpathian region—modern-day Romania—adds layers of depth and historical nuance to the character of Orlok. Played masterfully by Bill Skarsgård, Orlok’s guttural incantations in this long-extinct tongue serve as a chilling reminder of his preternatural age and his rootedness in the haunted lands of the Carpathians.

The Linguistic Choice: Why Dacian?

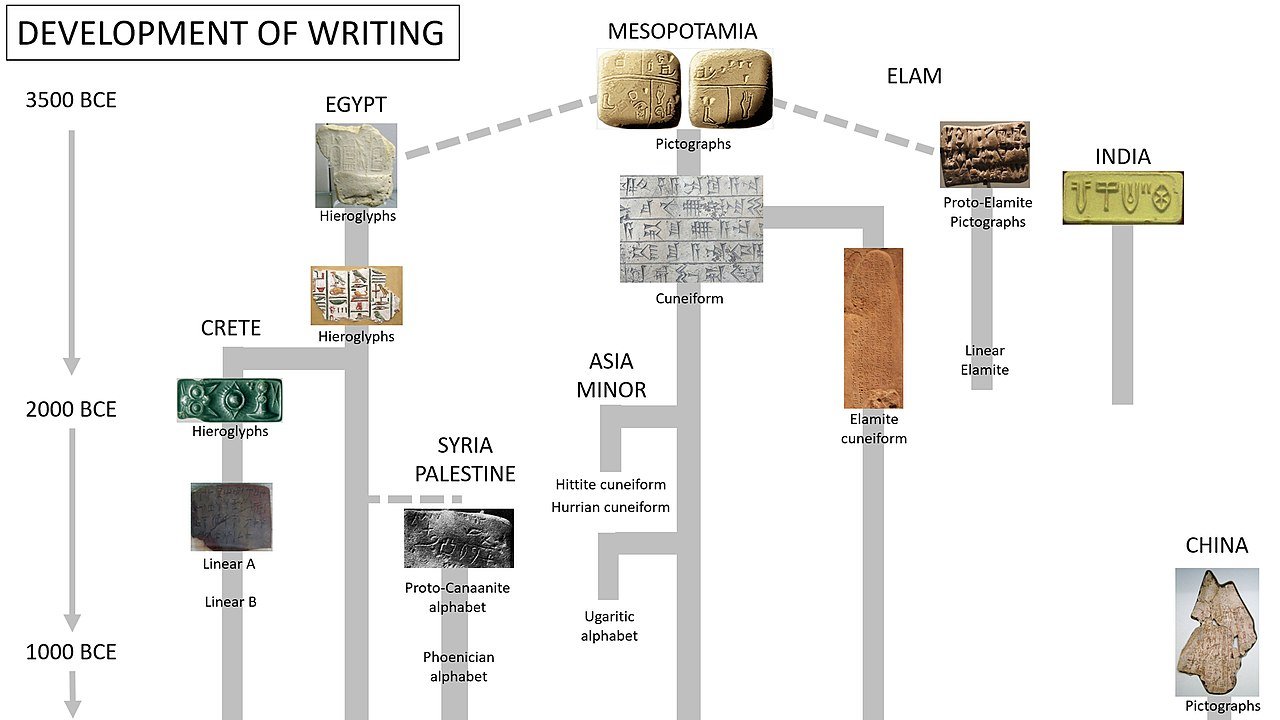

While many viewers might assume that Count Orlok, situated in the Romanian Carpathians, would speak Romanian, Eggers opted for Dacian to reflect Orlok's ancient lineage. Romanian, while rooted in the region, is a Romance language that evolved after the Roman Empire's conquest of Dacia in the 2nd century AD. Dacian, however, predates this, tracing its origins to the indigenous peoples of the area before Romanization. The Dacian language vanished around 500 AD, leaving only faint traces in place names, plant names, and substratum influences on modern Romanian.

Eggers explained his choice in an interview:

"Orlok is an ancient noble, predating even the foundations of the Romanian Empire. He needed a voice that felt as timeless and forgotten as his own existence. Dacian was perfect—it’s a spectral presence, much like Orlok himself."

For a director renowned for his fastidious attention to historical and cultural detail, this decision was far from arbitrary. Eggers collaborated with linguists and historians to reconstruct portions of the language, relying on comparative linguistics and what little documentation exists of Dacian. While the language itself remains largely mysterious, with only fragments preserved in Greek and Latin texts, these elements were sufficient to craft a haunting linguistic tapestry.

The Historical Context of Dacian

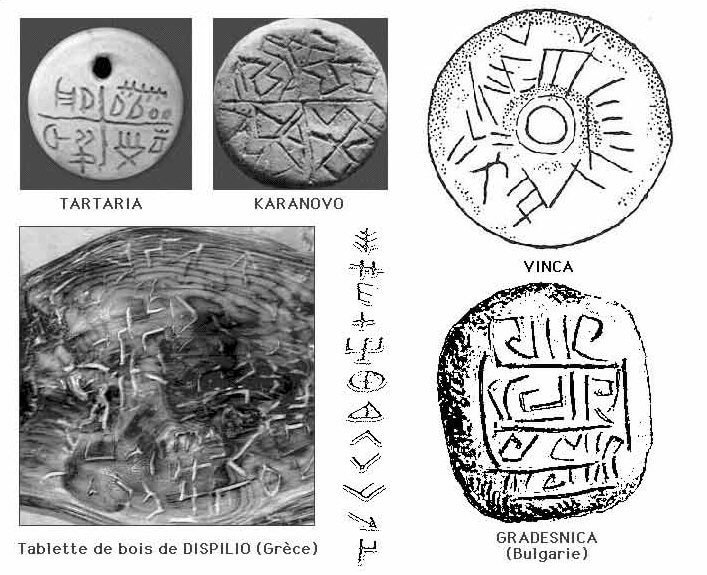

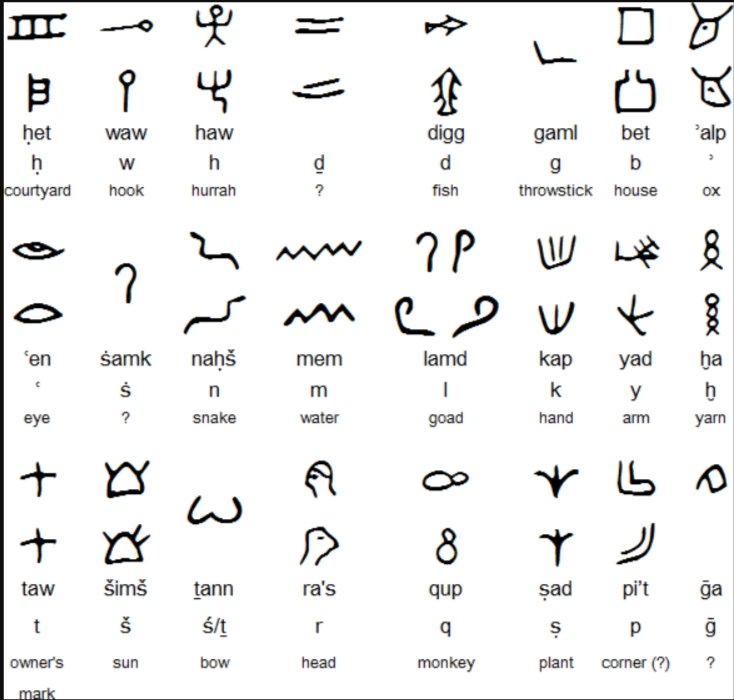

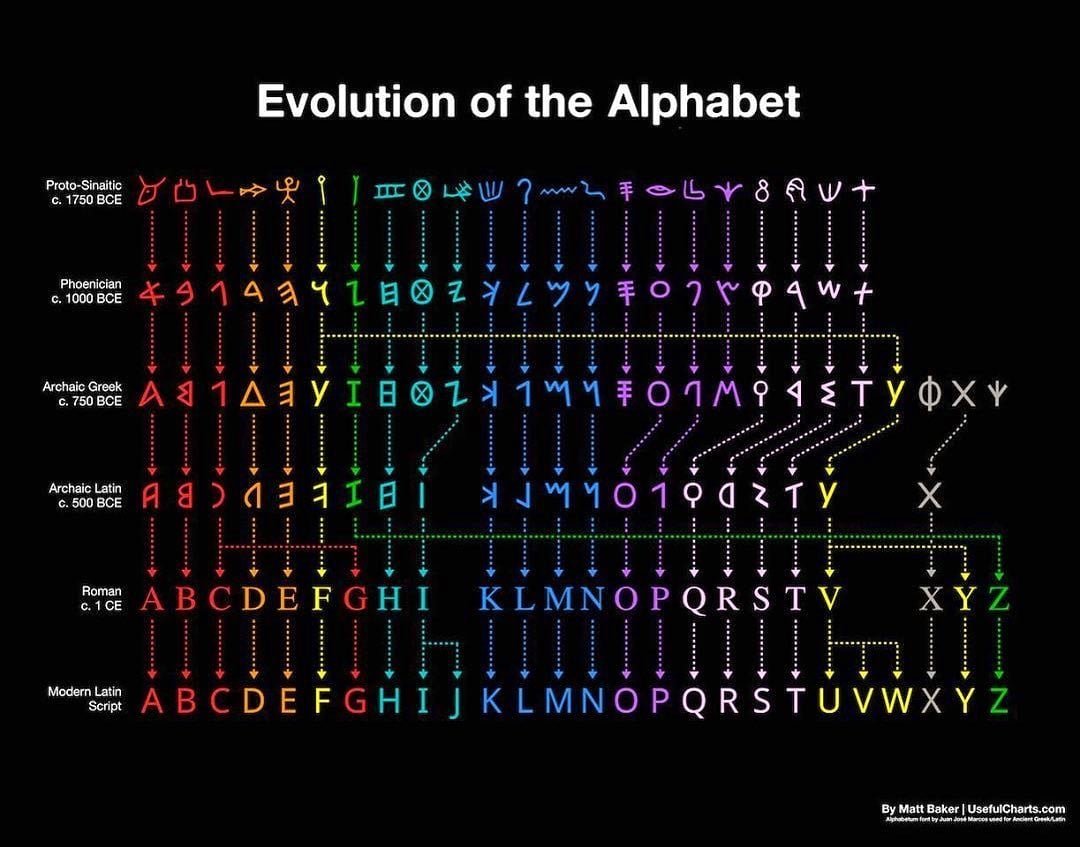

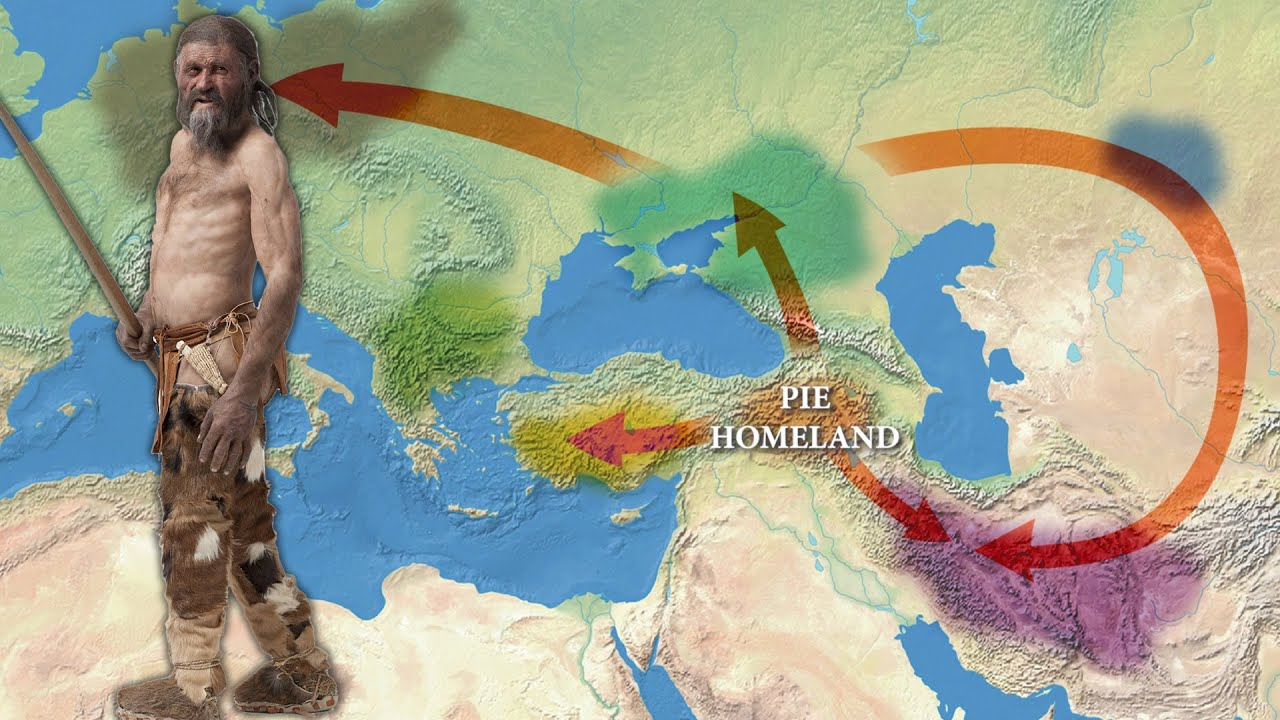

The Dacians were a Thracian tribe that inhabited present-day Romania, as well as parts of modern Bulgaria, Serbia, and Hungary. According to linguists, the Dacian language is believed to have originated from Paleo-Balkan Thracian and likely shared similarities with Illyrian, languages classified as residual languages of the Indo-European family. These languages are characterized by limited written records, making their precise interpretation and placement within the Indo-European genealogical tree particularly challenging. While these languages are thought to belong to the Indo-European family, the details of their grammatical structure remain largely unknown, as documentation is mostly confined to short inscriptions, place names, and personal names preserved by ancient authors and lexicographers. The phonological structure of Dacian is hypothetical, reconstructed through place names, river names, and plant names recorded in ancient sources such as those of Dioscorides and Pseudo-Apuleius.

Despite its extinction, Dacian left traces in the Romanian language, primarily as linguistic substrata. Words such as brânză ("cheese") and mal ("riverbank") are believed to have Dacian origins. These linguistic remnants serve as echoes of a culture that once flourished in the shadow of the Carpathian Mountains.

Dacia's map from a medieval book made after Ptolemy's Geographia (c. 140 AD)

The Cinematic Execution: Dacian in Nosferatu

Bringing Dacian to life in Nosferatu was no small feat. Eggers enlisted Romanian screenwriter Florin Lăzărescu and consulted with linguists specializing in extinct Balkan languages. Bill Skarsgård, renowned for his transformative performances, trained rigorously to deliver his lines in this reconstructed language. His haunting delivery, characterized by drawn-out syllables and guttural vibratos, imbued Count Orlok with an otherworldly presence.

The use of Dacian extended beyond dialogue. Eggers integrated the language into the film’s score, with the choir chanting in Dacian during key scenes. Composer Mark Korven collaborated with linguists to craft these chants, blending the ancient tongue with modern musical techniques to evoke a sense of primordial dread.

This linguistic layer added authenticity to the film’s historical setting. Orlok’s castle, looming ominously in the Carpathians, felt less like a Gothic fantasy and more like an archaeological relic, with its inhabitant an unsettling artifact of a bygone era.

The Impact of Dacian on Orlok’s Characterization

By speaking Dacian, Orlok becomes more than just a vampire; he is a relic of an ancient world, a being whose existence predates modern civilization. His use of Dacian underscores his otherness—not only as a creature of the night but as a remnant of a culture swallowed by time. When Orlok casts his spells or utters incantations in this archaic tongue, he bridges the gap between myth and history, blurring the lines between legend and reality.

The choice of Dacian also adds a layer of tragedy to Orlok’s character. He is not merely undead; he is untethered from time, clinging to a language and culture that no longer exist. In this sense, his monstrousness is amplified by his isolation—not only from humanity but from history itself.

How Cinema Revived Interest in Historical Comparative Linguistics

The use of the Dacian language in Nosferatu demonstrates the power of language in storytelling. Count Orlok, through his forgotten language, becomes a living monument to an ancient culture lost to time. The Dacian language grants Orlok an identity beyond that of a typical vampire, transforming him into a symbol of a heritage that continues to haunt collective memory. When Orlok delivers his incantations or chants hymns in Dacian, the boundaries between myth and reality blur, bridging history with the imaginative realm of horror.

The introduction of Dacian in Nosferatu rekindled public interest in historical comparative linguistics and extinct languages. The film used the language as an aesthetic element but also highlighted its importance as a remnant of historical memory. By reviving this extinct language, director Robert Eggers not only enriched the narrative of the film but also sparked renewed curiosity about the history and culture of the Dacians. Linguists and historians have observed increased public interest in Dacian following the movie's release, with some suggesting that the project could lead to further scholarly research on this enigmatic language.