A 2,400-year-old Greek relic stolen half a century ago has finally come home.

A German woman who stole the top of an ancient Greek column 50 years ago has returned the object to Greece, putting an end to the long absence of the 2,400-year-old artifact from its homeland.

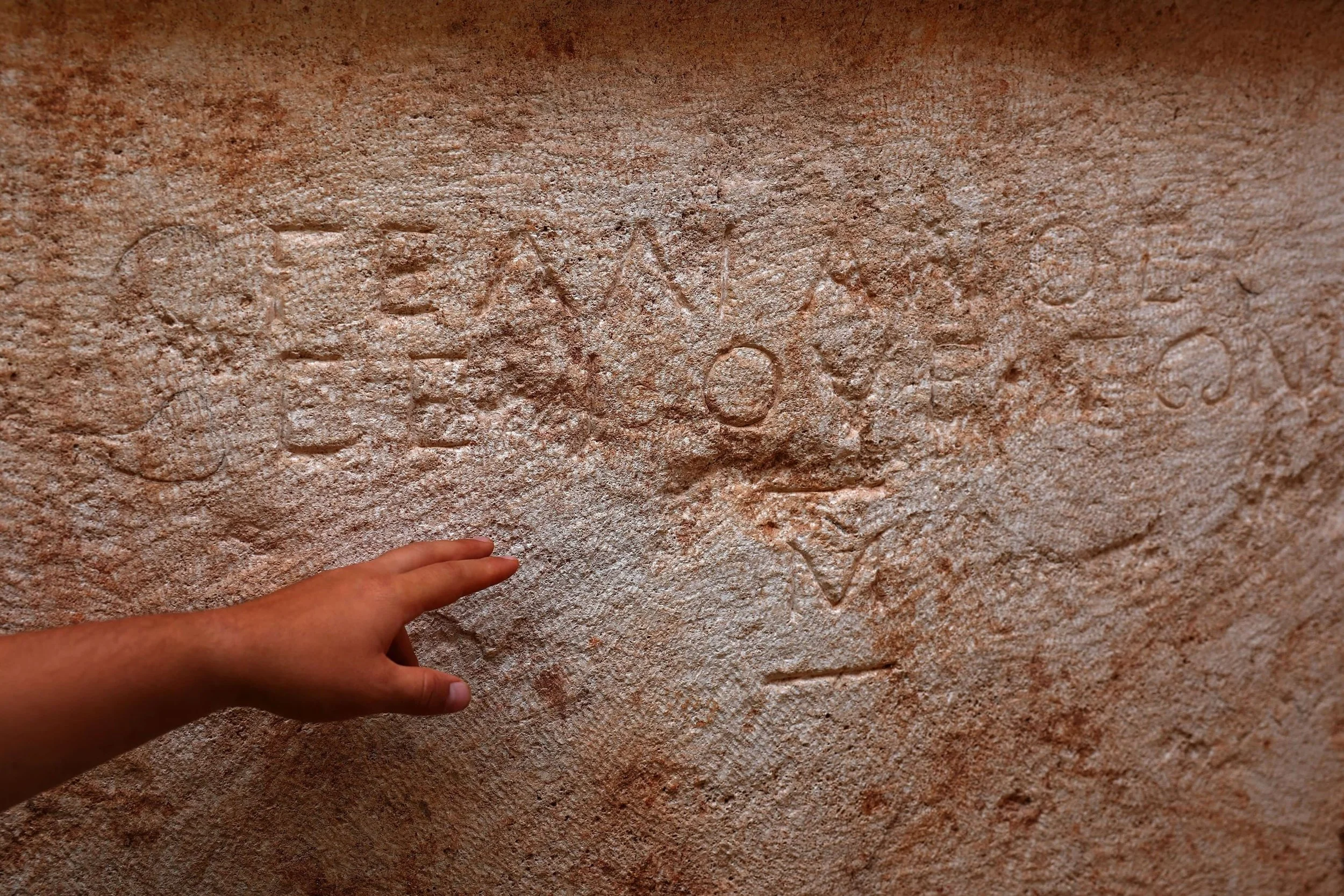

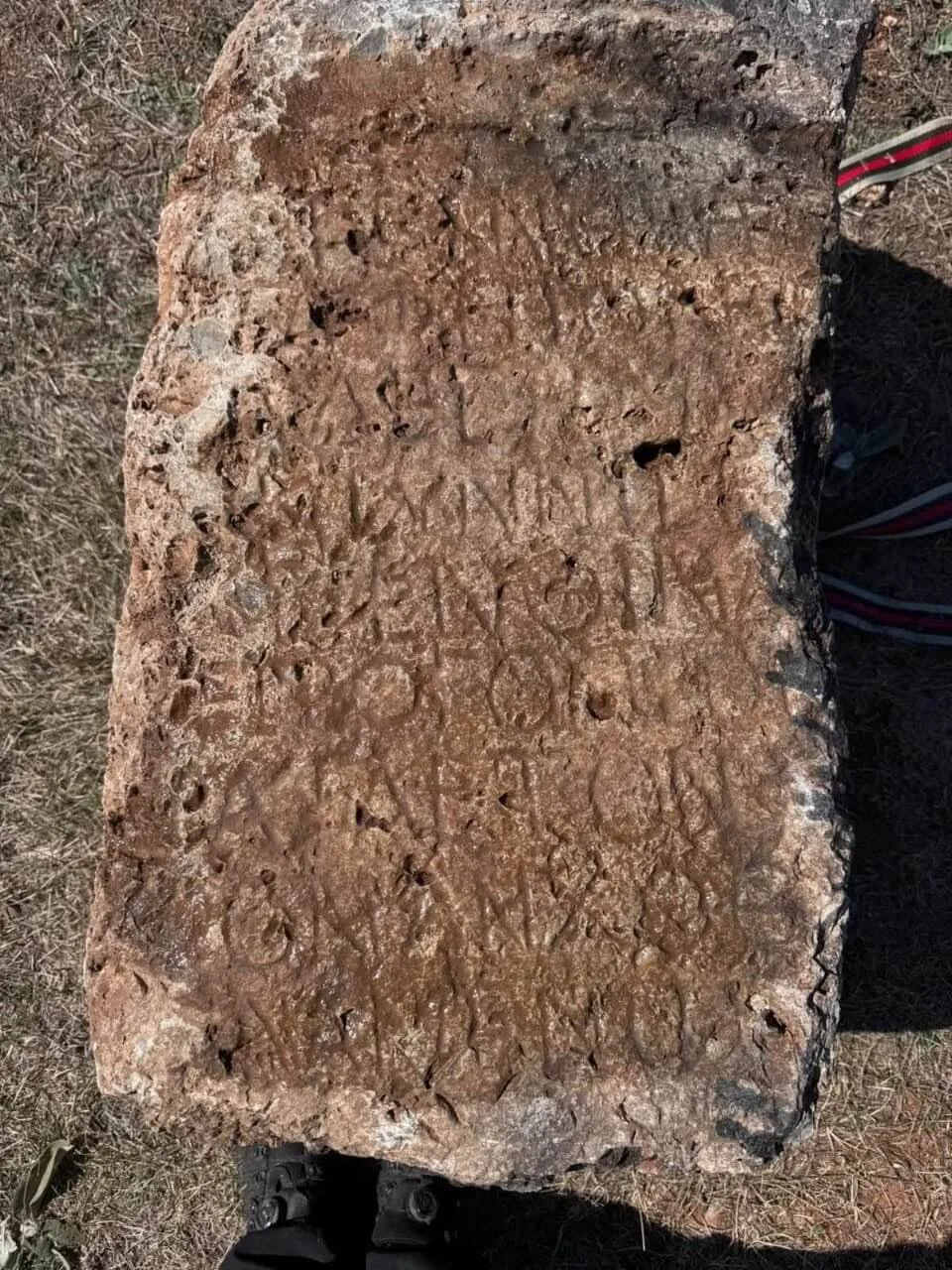

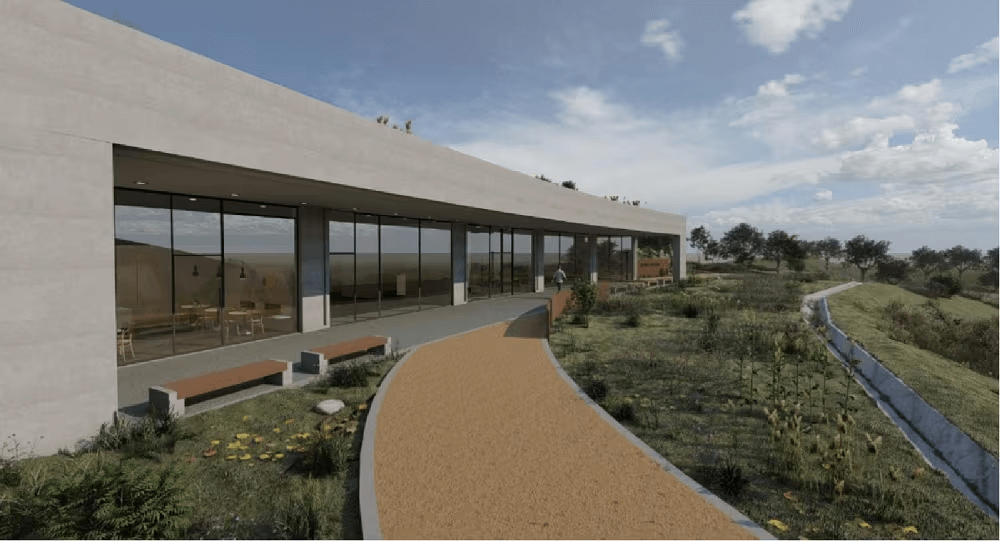

The Ionic column capital, made of limestone and measuring roughly 23 cm in height and 33 cm in width, had been removed from the Leonidaion, a 4th-century BC guesthouse in Ancient Olympia. According to Greek authorities, the relic was handed back on Friday (10/10) during a ceremony at the Ancient Olympia Conference Center, after the woman voluntarily gave it to the University of Münster in Germany, which organized and ensured its repatriation.

She took it in the 1960s

The German woman had taken the capital during a visit to the archaeological site in the 1960s and kept it for decades before deciding to return it. She said she was motivated by the university’s recent efforts to repatriate looted antiquities. The Greek Ministry of Culture praised her “sensitivity and courage”, noting that her action shows that “it is never too late to do the right thing.”

This is the third major antiquity repatriated to Greece by the University of Münster in recent years. In 2019, the so-called “Louis Cup,” associated with the Olympic champion of 1896, was returned; in 2024, a marble male head from Roman-period Thessaloniki was also repatriated.

“Culture and history know no borders”

“This is a deeply moving moment,” said the Secretary General of Culture, Georgios Didascalou, during the handover ceremony. “This act proves that culture and history know no borders, but require cooperation, responsibility, and mutual respect. Every such return is an act of restoring justice and, at the same time, a bridge of friendship between peoples.”

Dr. Torben Schreiber, curator of the Archaeological Museum of the University of Münster, stated that the institution will continue to return any object proven to have been acquired illegally. “It is never too late to do what is right, ethical, and just,” he added.

The Leonidaion—named after its benefactor Leonidas of Naxos—is the largest building in the sanctuary of Olympia, built with Ionic columns around its perimeter to host distinguished visitors. The returned piece will now undergo conservation and be displayed at Ancient Olympia, according to officials.