Two thousand years ago, the Roman Empire was not only dominating vast territories on land but was also achieving what to many seemed impossible—engineering feats beneath the surface of the sea. Without oxygen tanks, modern wetsuits, or high-tech diving gear, the Romans designed and built underwater structures that would challenge even 21st-century architects. From harbors constructed directly on the sea floor to experimental diving methods, their ingenuity continues to astound scholars and engineers alike.

This little-known chapter of Roman innovation reveals a civilization that was not only mastering roads, aqueducts, and monumental architecture—but also the depths of the ocean itself.

Diving Without Modern Equipment

The idea of underwater exploration in the ancient world conjures images of brave mariners and mysterious wrecks, but the Romans took it a step further—they developed rudimentary diving technologies to stay submerged for extended periods.

Historical accounts, notably from Pliny the Elder and later Byzantine sources, refer to “urinatores”—professional divers employed in both military and civilian roles. These divers salvaged sunken cargo, explored wreckage, and assisted in underwater construction. But how did they breathe?

The simplest technique involved using hollow reed tubes, extending from the diver’s mouth to the surface. While this method limited movement and depth (due to pressure constraints), it allowed them to stay submerged just long enough for short tasks. For deeper or more complex dives, the Romans may have used primitive diving bells—air-filled metal or clay containers inverted and placed over the head. Though rudimentary, these devices trapped enough air to allow a diver to descend up to 30 meters for short periods, according to some reconstructions.

While archaeological remains of these devices are scarce, literary and artistic evidence suggests such innovations were indeed part of Roman maritime operations. The ability to work underwater—however limited—was crucial to the Empire’s coastal infrastructure.

Lifting Giants from the Deep: The Port of Caesarea

One of the most astonishing Roman engineering feats is the artificial harbor at Caesarea Maritima, located on the coast of modern-day Israel. Commissioned by Herod the Great and completed around 10 BCE, this massive port demonstrates the Empire’s capacity to construct directly into the sea—a task that remains challenging for today’s builders.

Using massive concrete blocks molded and poured underwater, Roman engineers created breakwaters and seawalls that formed a fully functional harbor. These structures were laid atop submerged timber frameworks, filled with volcanic ash-based hydraulic concrete, and lowered into place with stunning precision. Divers and support crews had to coordinate these efforts while battling currents and visibility—a testament to their training and ingenuity.

The entire operation at Caesarea required logistical mastery, including quarrying materials, transporting them by sea, and assembling them underwater. The port served as a vital naval and commercial hub, connecting Judaea to the broader Roman trade network. Despite centuries of erosion, parts of the harbor remain intact, preserved in part by the remarkable properties of Roman concrete.

Concrete that Sets Underwater: Rome’s Hydraulic Masterpiece

Perhaps the single most significant Roman innovation that made these feats possible was their hydraulic concrete, known today as opus caementicium. While modern Portland cement crumbles in saltwater over time, Roman marine concrete has proven to be incredibly durable—even strengthening as it ages.

The secret lay in its unique composition: a blend of lime (calcium oxide), volcanic ash (pozzolana), and rubble or gravel. When mixed with seawater, this combination triggered a chemical reaction that produced calcium-aluminum-silicate hydrates, creating a rock-like bond. This allowed the concrete to set underwater, hardening quickly and bonding with the surrounding materials, including natural rock.

Modern scientists only recently unraveled the precise chemistry of this process, and studies published in journals such as American Mineralogist and Nature Materials have shown that the Roman mix is not only environmentally resilient but also self-healing—crystals continue to grow within cracks over time, strengthening the structure.

This discovery has profound implications for sustainable construction today. Several research groups are now looking to revive Roman concrete as a greener, longer-lasting alternative to modern cement, which is one of the largest industrial producers of CO₂ globally.

A Legacy Beyond Monuments

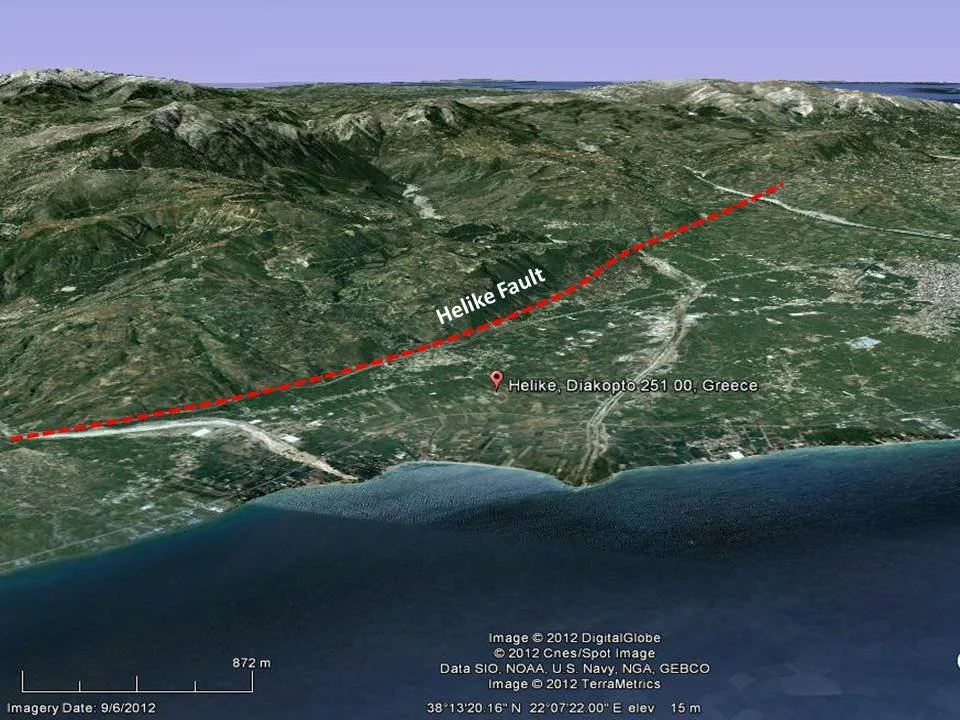

What makes Roman underwater engineering even more remarkable is that it was not confined to isolated cases. From Pozzuoli and Naples to Antibes and Alexandria, harbors, piers, and breakwaters constructed using the same principles stretched across the Mediterranean. These were not symbolic structures—they were functional lifelines for trade, military mobility, and urban development.

In some cases, Roman engineers also built submerged foundations for lighthouses, sea walls, and even fish tanks (piscinae) used in luxury villas. The tools and techniques they developed were systematic and adaptable, based on modular principles and transmitted across the Empire via military and administrative networks.

The broader philosophical implication is just as striking: Rome did not simply expand geographically—it expanded technologically, pushing the limits of what was possible in materials science, logistics, and the manipulation of nature. Their ability to “build the impossible” was a cornerstone of imperial identity and propaganda. For emperors like Augustus and Trajan, engineering marvels symbolized Rome’s destiny to tame the world—above and below sea level.

Reclaiming the Depths: Modern Insights from Ancient Mastery

Today, maritime archaeologists are increasingly aware of the sophistication of Roman underwater works. Dive surveys at Caesarea, Baiae, and other coastal sites continue to reveal foundations, mortar samples, and even wooden pilings preserved in anaerobic seabed conditions.

Meanwhile, collaborations between scientists and classicists have helped re-contextualize Roman maritime practices. Using AI, 3D scanning, and chemical analysis, we are not only rediscovering lost techniques but also reintegrating them into modern engineering discussions. The ancient world is no longer just a source of inspiration—it is a source of solutions.

As we face rising seas and fragile coastlines, Roman innovations may very well inform the next generation of resilient infrastructure. In an age that often praises novelty, it is humbling to remember that the foundations of some of our best ideas were literally laid underwater by Roman hands two millennia ago.

Conclusion

Rome’s mastery of underwater engineering is more than an archaeological curiosity—it is a powerful reminder of human ingenuity and adaptability. With limited tools and profound insight into materials, pressure, and construction, Roman engineers conquered not only lands but the seas themselves. Their legacy endures not just in submerged ruins, but in the engineering wisdom we are only now beginning to fully understand.

From breathing beneath the waves to lifting entire harbors from the sea floor, the Romans showed that even in the most challenging environments, vision paired with innovation can build what others think impossible.