On the cusp of spring, with the vernal equinox breathing new life into the dormant soils of winter, the ancient celebration of Nowruz commences—a festivity that stretches back over two and a half millennia, transcending borders and ethnicities. A general sense of renewal permeates the nations connected by the rich threads of Persian heritage as the earth tilts to bless the northern hemisphere with the first tender sunrays. This year, on March 20, 2024, the Persian New Year unfurls its vibrancy once again.

Nowruz, meaning 'new day' in Persian, is not just a marking of time but a profound expression of nature's perennial cycle of rebirth. The celebration of Nowruz is a cultural embodiment of rebirth and the rekindling of life, mirrored in the sprouting of green shoots and the blossoming of flowers that herald the arrival of spring.

The genesis of Nowruz is enmeshed with Iranian mythology and the tales of the majestic king Jamshid, a figure shrouded in the golden mists of legend and history. This sovereign, from the house of Pishdadian, is venerated for bequeathing this celebration to humanity, symbolizing not only the earth's awakening but also the triumph of light over darkness, of warmth over cold, of life over desolation.

The Pishdadian dynasty, enshrined in the annals of Persian lore, is revered as the progenitors of Iranian civilization. They were the harbingers of societal structures and agrarian advances, fostering prosperity and stability in ancient Iran. Their era is often romanticized as a golden age, free from suffering and filled with abundance—a utopian epoch that the Nowruz celebration aspires to recapture each year.

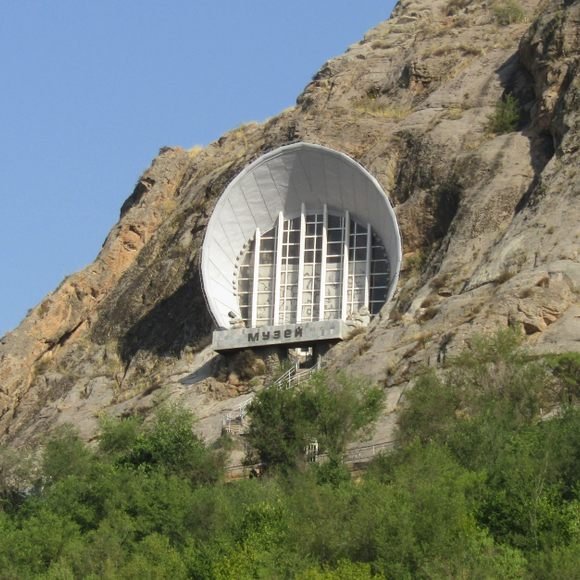

This New Year festivity has endured the passage of empires, resisted the erosion of time, and emerged as a resilient cultural institution. Today, Nowruz is observed by diverse ethnicities and nations, from the cradle of its birth in Iran to the steppes of Central Asia, and even in enclaves where Persian culture has left its indelible imprint.

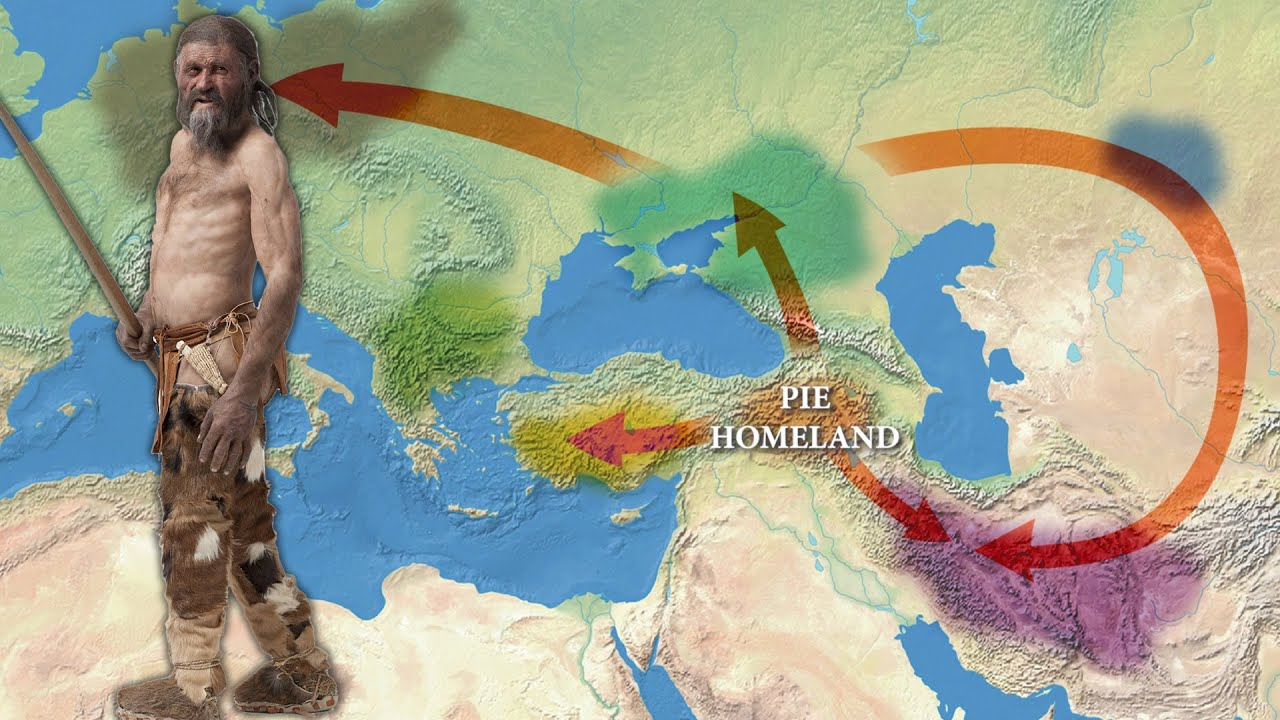

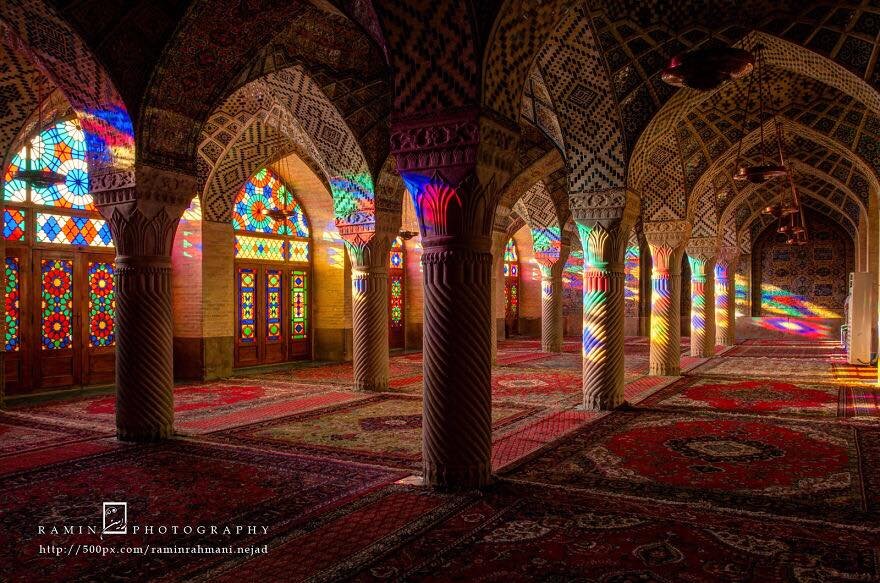

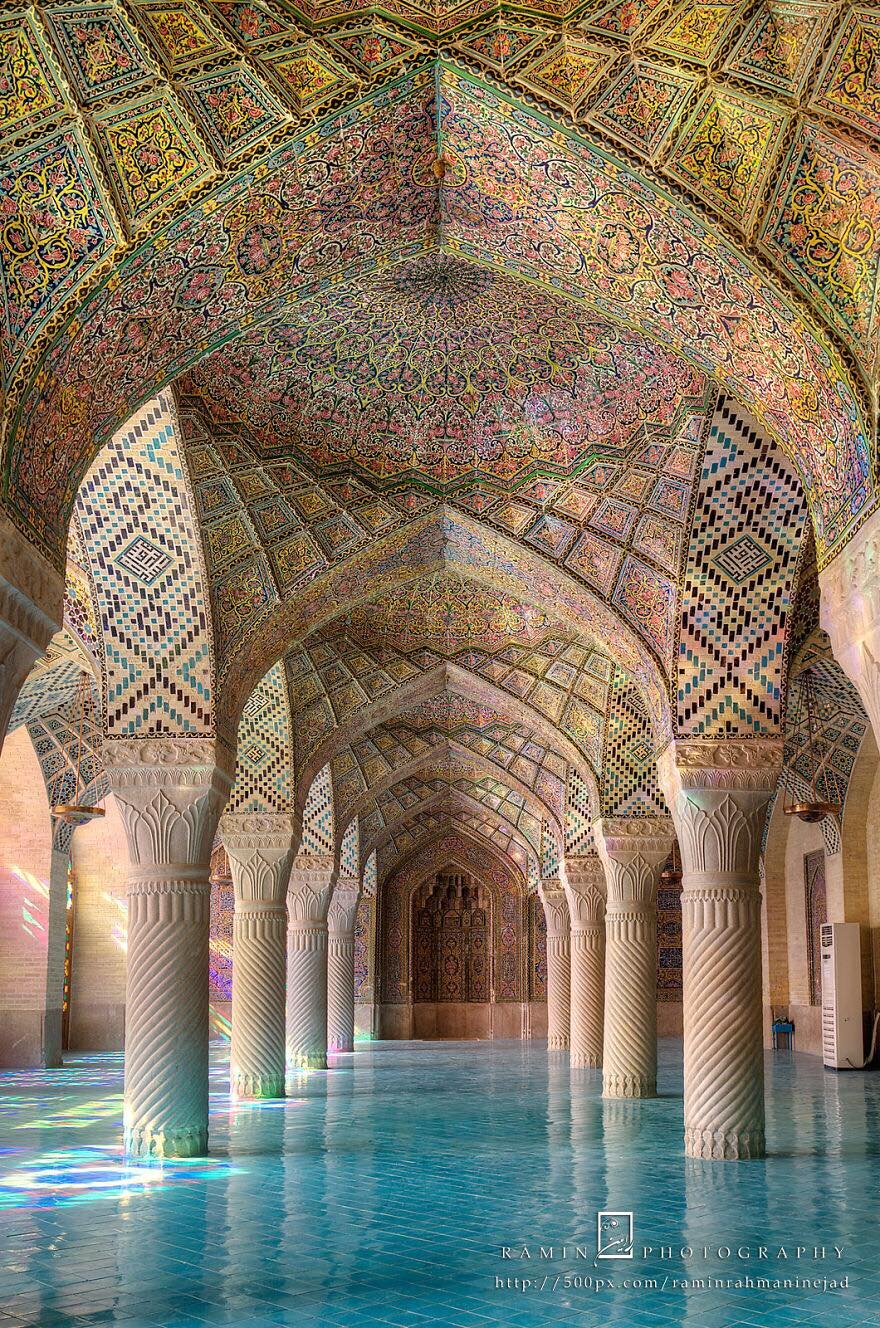

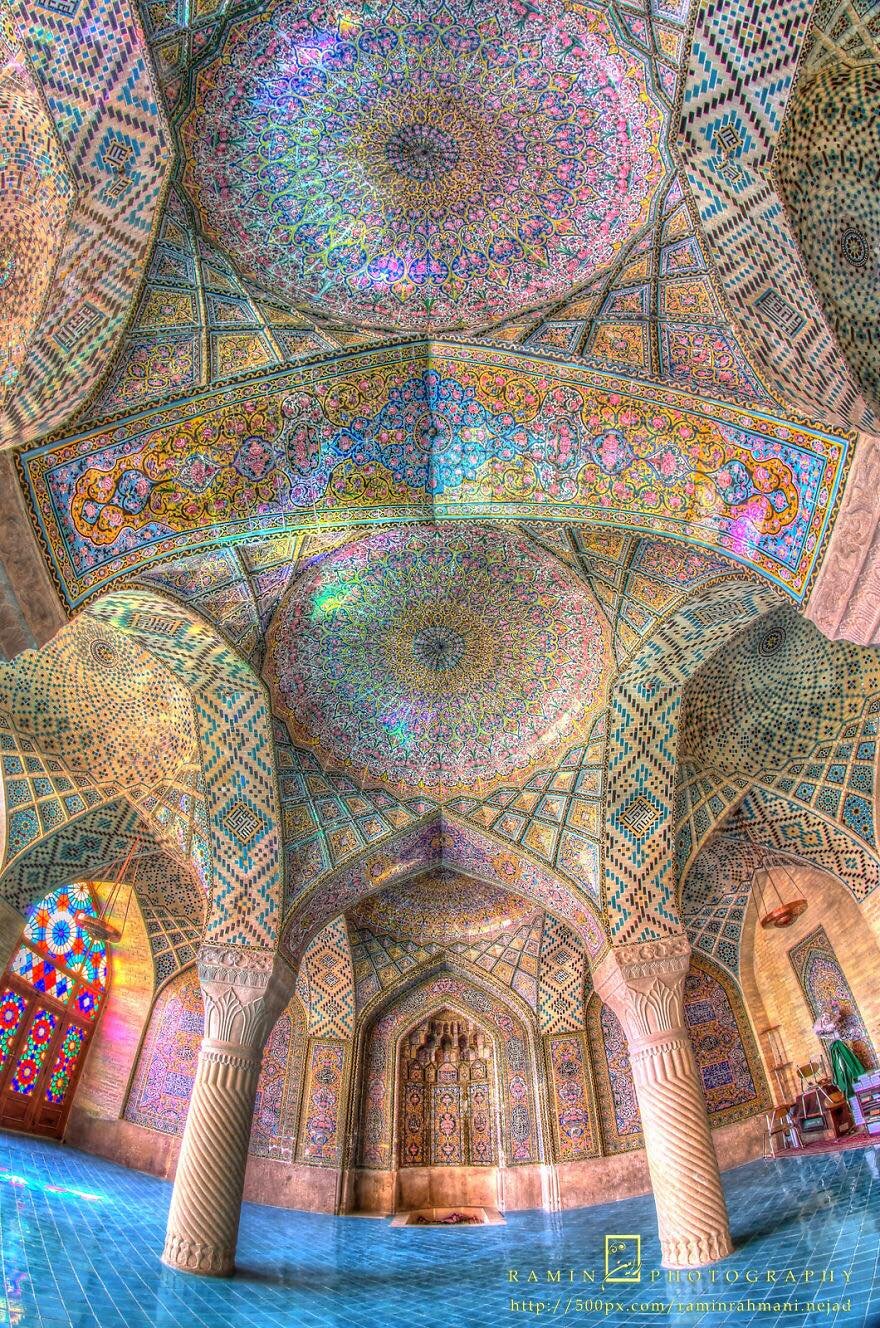

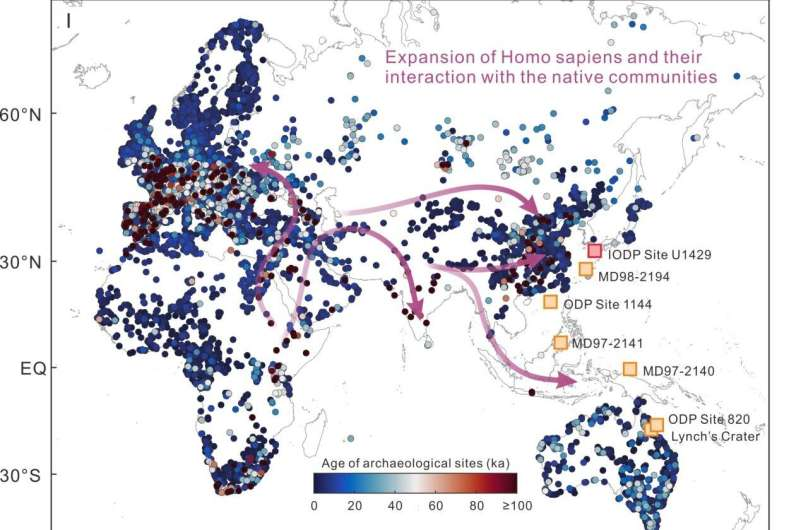

The map shown delineates the contemporary geographical embrace of Nowruz—a testament to the cultural exchange that has characterized the regions touched by Persian influence. It shows countries and regions where Nowruz is not only a time of festivity but also an official holiday, marking the commencement of the year in countries such as Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, among others.

In regions like the self-governing republics of Kabardino-Balkaria and Dagestan, as well as the states of Albania, Kosovo, and even beyond, Nowruz is celebrated by people who honor the shared heritage that threads through their history. This is a festival that binds communities, igniting a collective spirit of joy, unity, and anticipation for what the new year holds.

As Nowruz approaches, families and communities come together to engage in time-honored traditions, each element steeped in symbolism and age-old customs. From the setting of the Haft-Seen—a table adorned with seven items starting with the letter 'S' in Persian, each signifying a different hope for the new year—to the jumping over bonfires on Chaharshanbe Suri, the ritual acts of Nowruz are replete with meaning and a deep connection to the forces of nature and the cosmos.

In 2024, as in all years past, Nowruz will echo the footsteps of those who walked the ancient lands of Persia, a moving homage to the wisdom of forebears who saw in the earth's rebirth a cause for celebration and hope. It stands as a reminder that, despite the differences that distinguish one nation from another, there are timeless rhythms that unite us—a dance of the earth around the sun, a cycle of life, death, and rejuvenation that continues to inspire and bind humanity in a shared narrative of renewal and joy.