Hyperdiffusionism, a term that echoes through the corridors of pseudoarchaeology, proposes a singular, albeit controversial, narrative for the development and dissemination of cultural practices, technologies, and religious beliefs across ancient civilizations. This hypothesis, which has its roots in the early 20th-century scholarship of individuals like Grafton Elliot Smith, contends that a single progenitor spread the cultural branches of great civilizations far and wide, from the building of pyramids to the worship of solar deities.

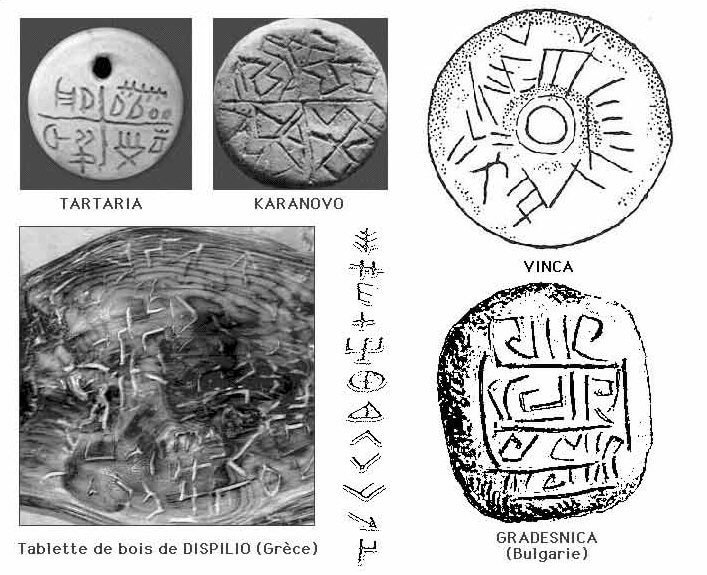

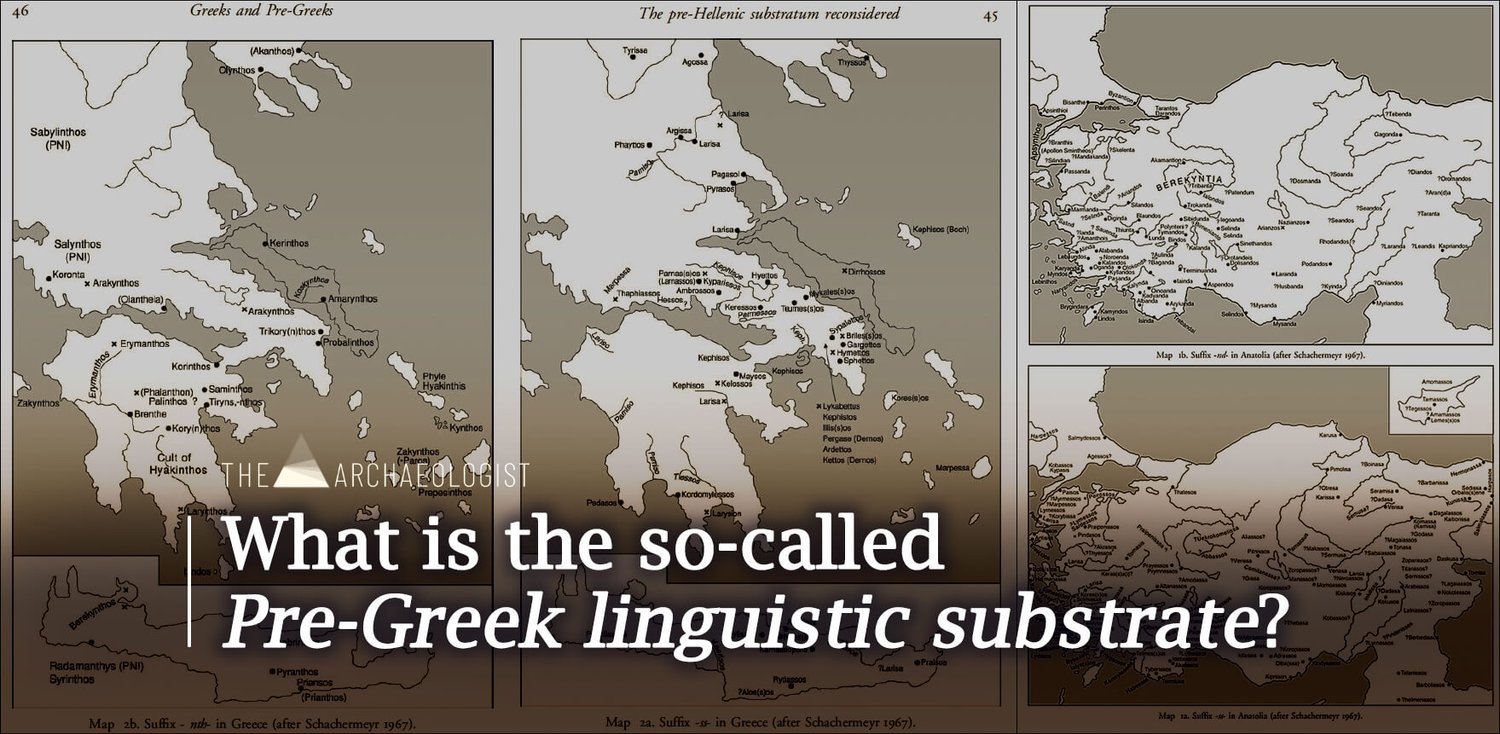

At the heart of hyperdiffusionism lies the contention that a singular, often mythical, civilization—be it Atlantis, Lemuria, or a historically recognized culture like ancient Egypt—acted as the cultural fountainhead from which all major civilizations drew their inspirations. This notion extends to various facets of human endeavor, including religious practices, architectural marvels like megaliths, and even the intricate process of mummification, pointing towards a linear transmission of ideas and practices across vast geographical expanses.

The Proponents and Their Propositions

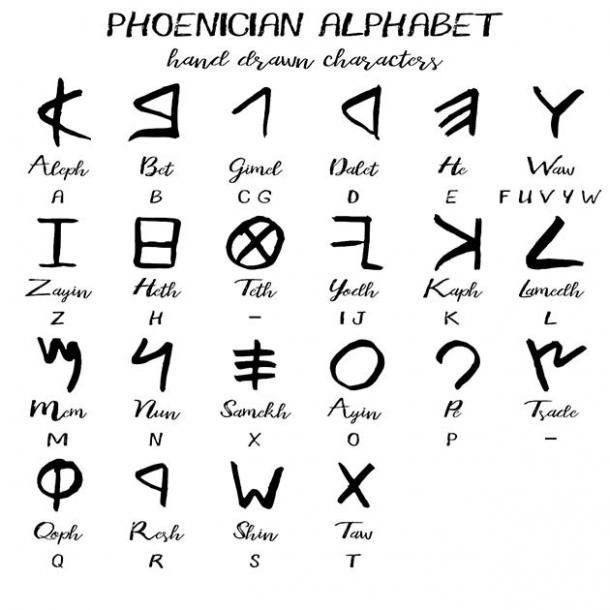

Grafton Elliot Smith, one of the most vocal advocates of this theory, attributed a wide array of cultural phenomena, from megalithic constructions to sun worship, to the diffusion of a so-called Heliolithic culture, with ancient Egypt posited as the epicenter of this cultural wave. Smith's claims, along with those of Charles Hapgood (who said that ancient sea kings mapped out a prehistoric world that was much more connected than was previously thought) and Barry Fell (who thought that Celts and Phoenicians came to New England), create an interesting web of civilization-spanning connections that are based on speculation rather than history.

Critiques and Counterpoints

The hypothesis, however, has not been without its detractors. Scholars like Alexander Goldenweiser and Stephen Williams have criticized hyperdiffusionism for its lack of empirical support and for often ignoring the possibility of independent invention and parallel development among different societies. The theory has been lambasted for its overreliance on coincidental similarities and its failure to account for the complexity and diversity of human cultures, which may develop similar solutions to universal challenges independently of one another.

Alice Kehoe has further criticized hyperdiffusionism as a "grossly racist ideology," suggesting that it underestimates the capacity of non-European societies for innovation and cultural complexity. Her work points towards a more nuanced understanding of cultural exchange, one that allows for independent invention and acknowledges the myriad ways in which societies can interact and influence each other.

Reflections on the Debate

The debate over hyperdiffusionism underscores a broader discussion about the nature of cultural exchange and development. While the theory itself may offer an oversimplified view of human history, it nevertheless opens up avenues for exploring the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations. It reminds us of the human propensity to seek connections and to understand our past as a shared narrative woven from the threads of diverse cultures.

In the end, hyperdiffusionism, with its grand narrative of cultural genesis and dissemination, serves as a testament to the human imagination and our enduring quest to trace the origins of the myriad practices and beliefs that bind us across time and space. While it may not provide a definitive account of our collective past, it certainly enriches the tapestry of human history with its bold conjectures and invites us to question, explore, and debate the myriad pathways through which cultures evolve and influence one another.