Research suggests a family of languages now spoken from Europe to India originated between the Caucasus and eastern Anatolia. But identity of first Indo-Europeans remains a mystery

A new DNA analysis, published on Thursday, August 26th, on 777 ancient genomes from across the so-called Southern Arc, namely Southern Europe and West Asia, redirects the cradle of Indo-Europeans and sheds light on the Proto-Greek prehistoric past.

The new study, published this Thursday, August 26, 2022 in Science, reports on genetic data extracted from 777 individuals who lived across the so-called Southern Arc, namely Southern Europe and West Asia. According to other more recent DNA data of ancient Anatolians, which raised new questions about the “spread” of Indo-European languages, it seems that Anatolians did not mix with steppe pastoralists during the early Bronze Age. It’s the only place where Indo-European-related languages were spoken even though there was no steppe ancestry.

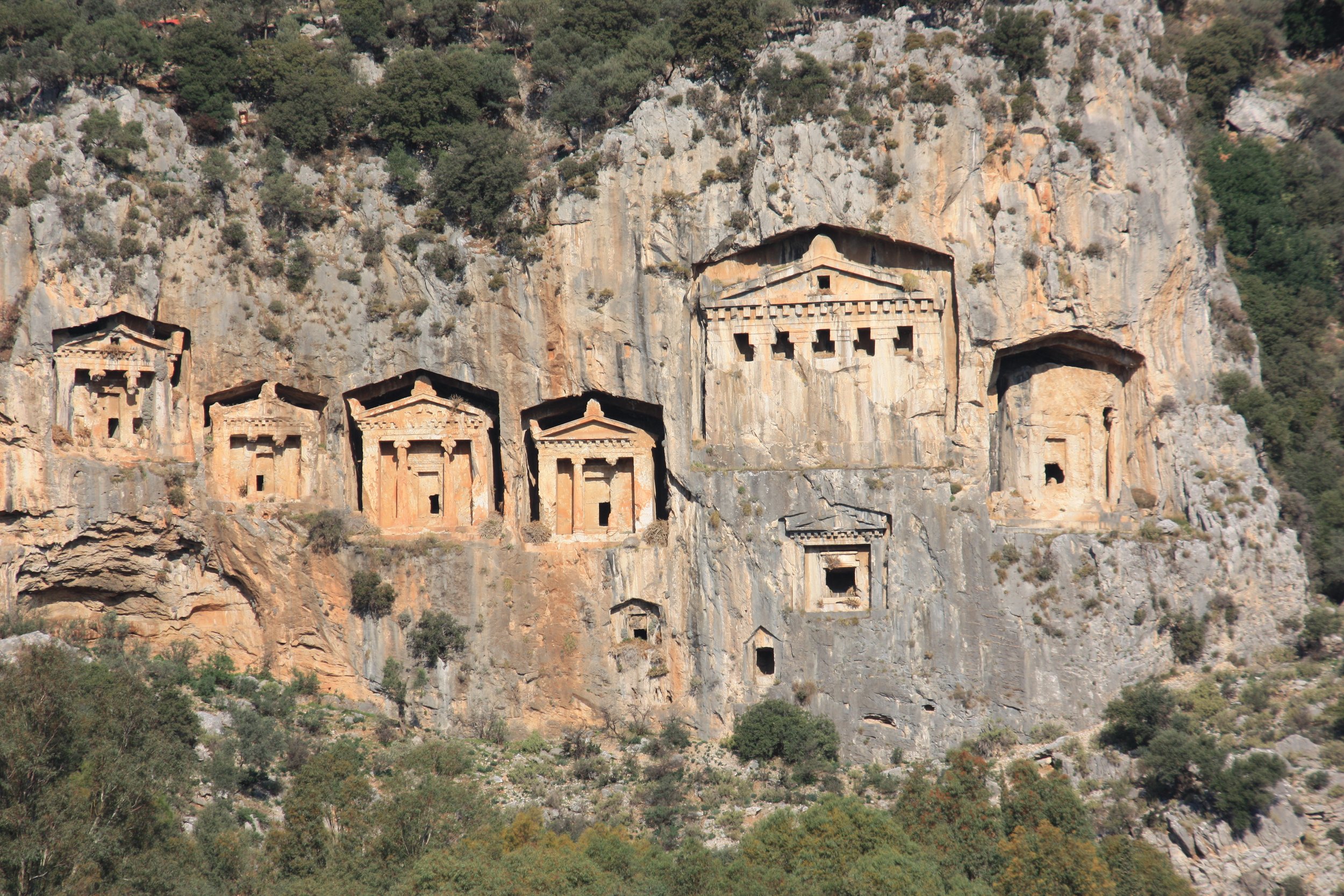

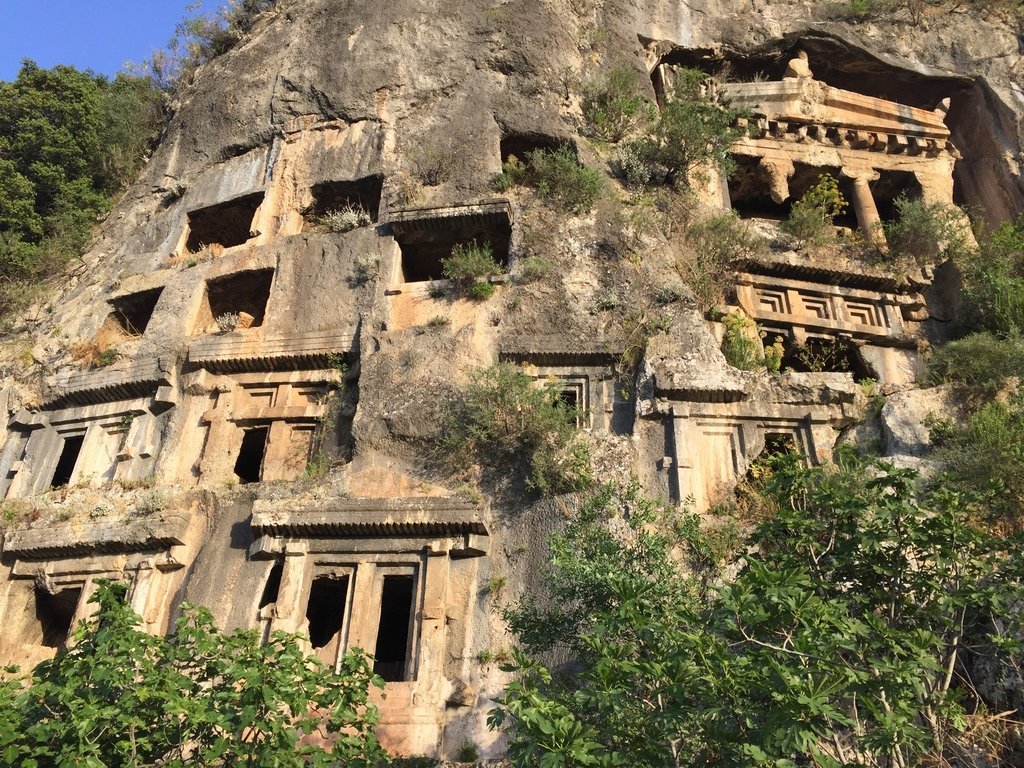

Ancient Anatolian peoples spoke the now-extinct Anatolian languages of the Indo-European language family, which were largely replaced by the Greek language during classical antiquity as well as during the Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods. The major Anatolian languages included Hittite, Luwian, and Lydian while other, poorly attested local languages included Phrygian, Palaic, Luwic, and Mysian.

Many partings, many meetings: How migration and admixture drove early language spread.

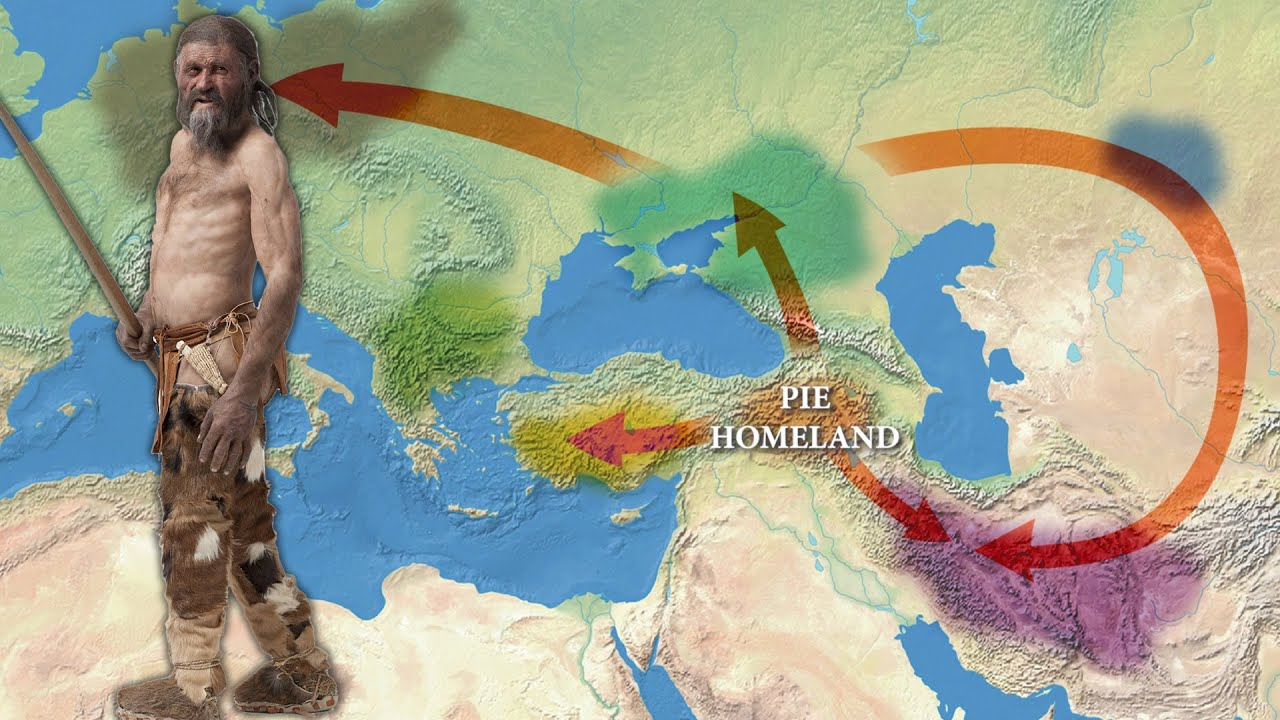

Westward and northward migrations out of the West Asian highlands split the Proto-Indo-Anatolian language into Anatolian and Indo-European branches. Yamnaya pastoralists, formed on the steppe by a fusion of newcomers and locals, admixed again as they expanded far and wide, splitting the Proto-Indo-European language into its daughter languages across Eurasia. Border colors represent the ancestry and locations of five source populations before the migrations (arrows) and mixture (pie charts) documented here.

The new Indo-European DNA research also shows that between five and seven thousand years ago there was a gradual increase of ancestry from the Caucasus in the Anatolian genome, probably by a series of migrations from the east, at the end of which about a third of the ancestry of Anatolians could be traced to somewhere in the Caucasus.

The fact that the same Caucasus component found in Anatolia comprises roughly fifty percent of the Yamnaya pastoralist genome further implicates the riddle of Indo-European languages. Given that this mysterious Caucasian link is the only ancestral commonality between the Yamnaya and the ancient Anatolians, it seems plausible that this enigmatic migration from the Caucasus brought the ancestral form of Indo-European to both of these peoples. Therefore, the homeland and the “first language” of Indo-Europeans must be placed somewhere in the Caucasus.

We must point out that these conclusions seem to primarily justify the eminent archaeologist Colin Renfrew and his Anatolian hypothesis, and they do line up quite well with contemporary archeological indications. The British archeologist compares the spread of the Indo-European languages to the spread of the Neolithic way of life from its Anatolian source in the seventh millennium BC (possibly the Caucasus).

Pylos Combat Agate” found in the Grave of the Griffin WarriorCredit: Photo Jeff Vanderpool. Courtesy

Renfrew also identifies this Neolithic demic diffusion with the spread of the Proto-Indo-European language and its subsequent differentiation into the daughter branches, i.e., the different Early Neolithic cultural phases across Europe.

The most interesting conclusion about prehistoric Greek populations comes from the new estimation of the Mycenaean steppe ancestry (about 1/10). The new study shows that this proportion is not uniform across the population. In fact, even among the elites, it was possible to find people who were not genetically related to Yamnaya (such as the genome of the so-called Griffin Warrior of Pylos).

According to experts, steppe migrants did not establish a rule over the natives and kept to themselves. Rather, they admixed with them, and there were still people without steppe ancestry with elite roles in mainland Greece, especially in Peloponnese. This means that during the later Mycenaean period in Greece, the new data suggest Yamnaya descendants had little impact on Greek social structure.

This explanation also once again confirms C. Renfrew and many other scholars, who have insisted throughout the last decades that the picture of the Proto-Indo-Europeans as warlike mounted nomads has been based not only on the misuse of linguistic paleontology but also on serious anachronism.