A Hittite Mystery Misinterpreted by Herodotus

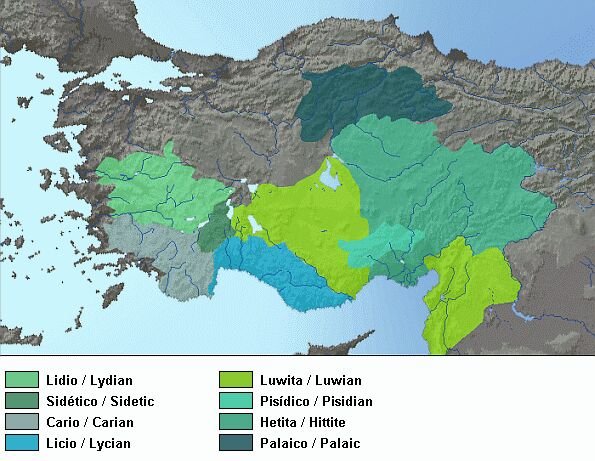

The figure on the relief is believed to be the Hittite King Tarkasnawa (also known as Tarkondemos), based on an inscription in the Luwian language that was found near the relief. The figure is shown wearing a pointed hat and a short skirt, both characteristic of Hittite depictions of their rulers. In one hand, he holds a spear, while the other hand is raised in a gesture of worship or salute.

However, the Karabel relief has a curious connection with the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who lived in the 5th century BC. In his "Histories", Herodotus described a monument that he encountered on his travels through what is now western Turkey. He wrote that this monument depicted an armed warrior and was inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphics.

This statement by Herodotus has caused some confusion among scholars, as the Karabel relief is clearly not Egyptian in style or script but Hittite. It appears that Herodotus made a mistake in his identification. This mistake may be due to his unfamiliarity with the Hittite Empire and its language, as it had already collapsed several centuries before his time and its history and culture were not yet widely known or studied.

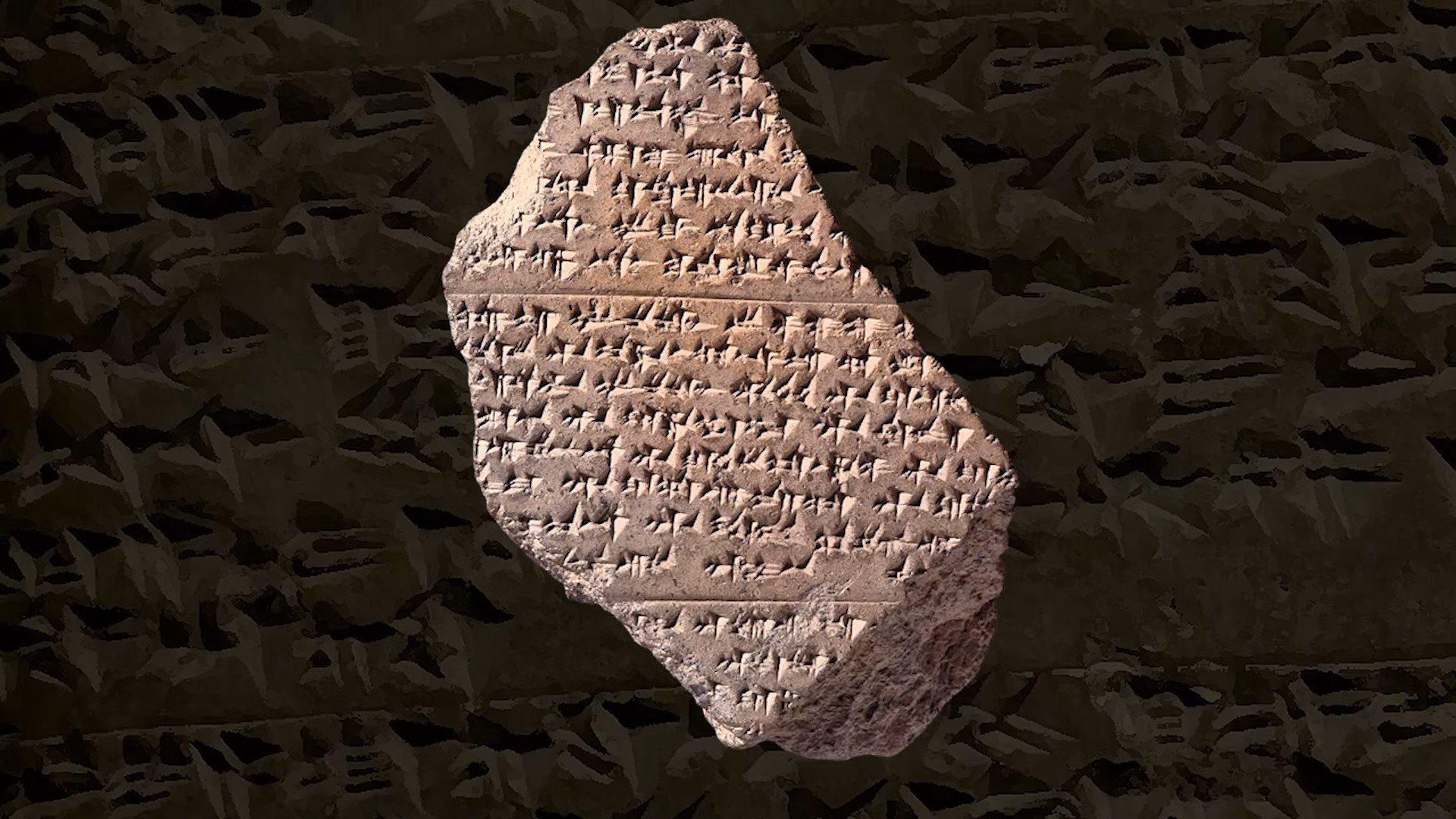

Moreover, the script on the Karabel relief is not hieroglyphic but rather in a form known as Luwian hieroglyphs or Anatolian hieroglyphs, which is quite distinct from Egyptian hieroglyphics. Luwian hieroglyphs were used in the region during the 2nd and 1st millennia BCE, notably by the Hittite and Luwian civilizations. Therefore, Herodotus might have confused this with the more famous Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Thus, Herodotus's mistake provides us with an interesting example of the limitations and challenges of historical and archaeological interpretation, especially in times when knowledge about ancient cultures was still limited or obscured by time. It also reminds us of the often complex and nuanced nature of ancient interactions and influences and the role of modern archaeological and linguistic studies in helping to shed light on these historical riddles.

Herodotus may have made reference to the monument in his history, identifying the carved figure as Egyptian pharaoh Sesostris as follows:

"... in Ionia there are two figures of this man carved upon rocks, one on the road by which one goes from the land of Ephesus to Phocaia, and the other on the road from Sardis to Smyrna. In each place there is a figure of a man cut in the rock, of four cubits and a span in height, holding in his right hand a spear and in his left a bow and arrows, ... and from the one shoulder to the other across the breast runs an inscription carved in Egyptian hieroglyphics, saying, 'This land with my shoulders I won for myself."

(Herodotus II.106)

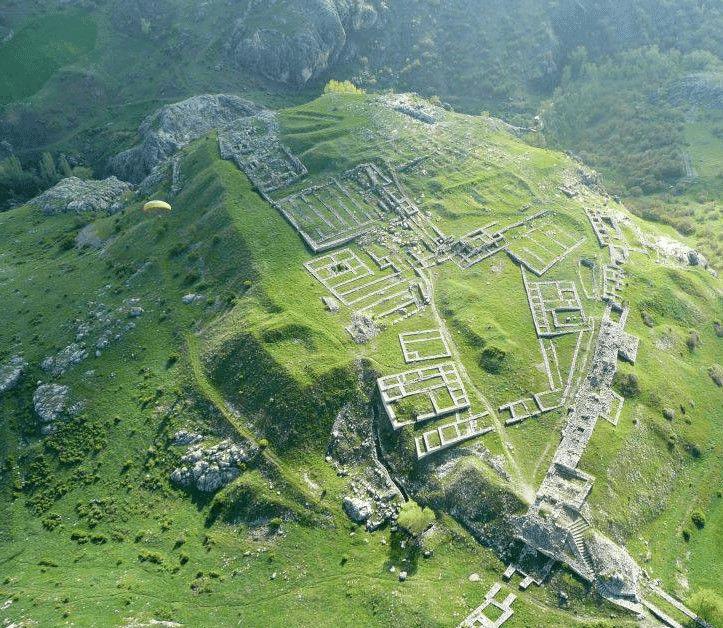

The Sardis-Ephesus route passes via Karabel Pass instead of the historic Sardis-Smyrna road, and it is important to take into account that the Ephesus-Phocai road is located much to the south. Herodotus' description was either inaccurate, or it's possible he was referring to a separate but related relief. The Torbal relief's recent discovery suggests that the area may have housed a number of other monuments of a similar nature. It goes without saying that the figure in the relief is not a ruler of Egypt. David Hawkins published the reading of the Karabel A inscription in 1998. Hawkins reads the inscription's three lines as follows:

Tarkasnawa, King of Mira (land).

[Son of] Alantalli, King of Mira land.

Grandson of ..., King of Mira land.

The reading of Alantalli is uncertain. In addition, even though the grandfather's name cannot be read, it has been hypothesized that it is Kupanta-Kuruntiya. Tarkondemos, who is seen in a few Boazköy seals, is also identified as Tarkasnawa by Hawkins reading. The Tarkasnawa reading has received widespread support from academics. The Hittite domain's vassal kingship of Mira was led by Alantalli, who is known to have lived during Tudhaliya IV's reign. As a result, his son Tarkasnawa should have lived during the reigns of Tudhaliya IV and/or Suppiluliuma II, placing the monument around the end of the 13th century BC.