Protowriting, ideographic systems, or early mnemonic symbols came before more advanced writing systems in the evolution of writing in human societies (symbols or letters that make remembering them easier).

A subsequent development is true writing, in which the content of a spoken language is encoded so that another reader may reasonably reconstruct the identical utterance written down. It differs from proto-writing, which frequently forgoes recording grammatical words and affixes, making it harder or even impossible to reassemble the precise meaning intended by the writer unless a substantial amount of context is already known in advance.

Writing innovations

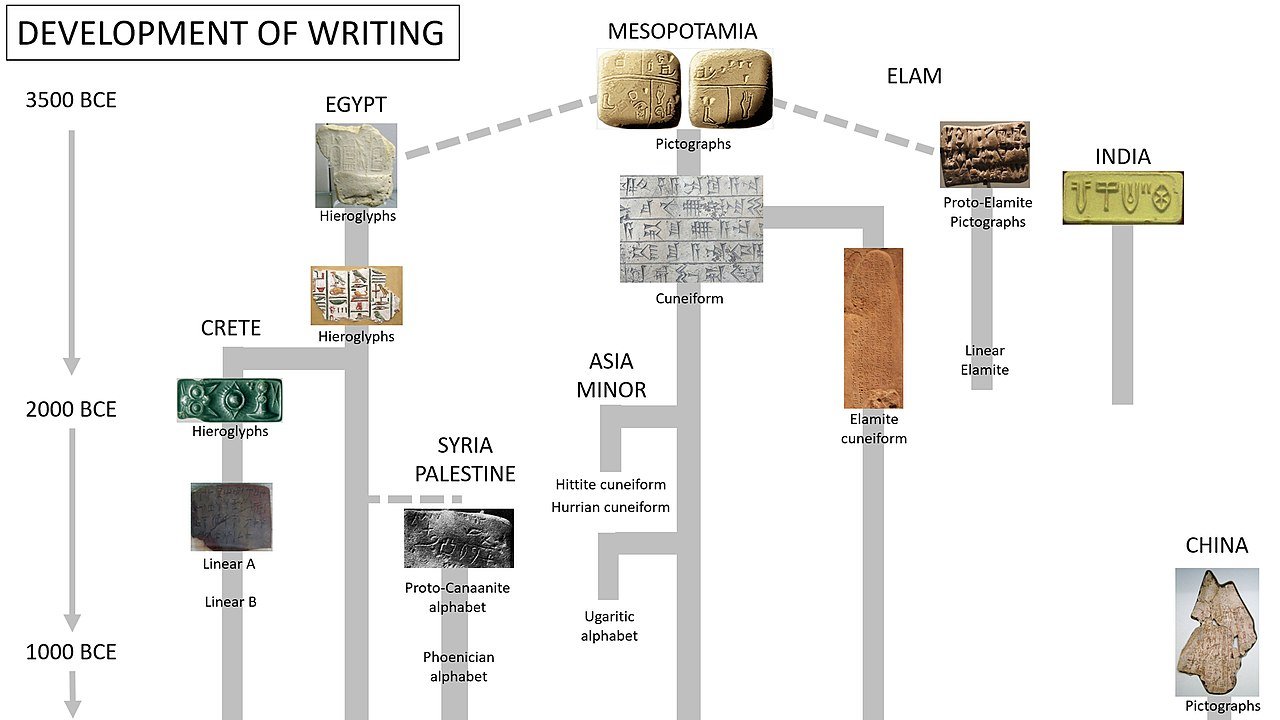

The idea that writing originated in a single civilization and was called "monogenesis" persisted for a long time. According to academics, all writing originated in Mesopotamia's ancient Sumer and spread around the world as a result of cultural diffusion. This argument holds that traders or merchants traveling between geographical locations passed on the idea of representing language by written signs, though perhaps not necessarily the specifics of how such a system operated.

The finding of ancient Mesoamerican scripts, far from Middle Eastern sources, demonstrated, however, that writing had been created more than once. In at least four ancient civilizations, including Mesopotamia (between 3400 and 3100 BCE), Egypt (about 3250 BCE), China (1200 BCE), and lowland portions of southern Mexico and Guatemala, writing may have independently originated (by 500 BCE).

Some academics have suggested that ancient Egypt "The earliest authentic examples of Egyptian writing differ from Mesopotamian writing in both structure and style, indicating that they must have emerged independently. Although there is still a chance that Mesopotamian "stimulus dispersion" occurred, the influence could not have extended beyond the dissemination of an idea."

Because there is no evidence of communication between ancient China and the Near Eastern literate civilizations, as well as because Mesopotamian and Chinese approaches to phonetic representation differ, it is thought that ancient Chinese characters are independent creations.

The Vinča symbols.

The Rongorongo script of Easter Island, the Vina symbols from about 5500 BCE, and the Indus script of the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilization are all controversial. Since none have been translated, it is unclear if they all represent real writing, protowriting, or something entirely different.

The earliest coherent texts date from around 2600 BCE, and Sumerian archaic (pre-cuneiform) writing and Egyptian hieroglyphs are usually regarded as the earliest authentic writing systems. Both developed out of their ancestors' proto-literate symbol systems between 3400 and 3100 BCE. The Proto-Elamite script belongs to roughly the same time frame.

writing methods

Writing systems are distinct from symbolic communication systems. For most writing systems, reading a text requires some knowledge of the spoken language that goes along with it. In contrast, it's not always necessary to have a prior understanding of a spoken language to use symbolic systems like information signs, paintings, maps, and mathematics. Every human group has its own language, which is thought by many to be a natural and essential aspect of mankind.

Writing system development has been intermittent, uneven, and delayed, and old oral communication systems have only been partially replaced. Writing systems generally develop more slowly after they are formed than their spoken counterparts and frequently preserve traits and idioms that have been lost to the spoken language.

Three writing standards are thought to apply to all writing systems. First, writing must be comprehensive; it must have a meaning or purpose, and it must make a point or be able to convey that message. Second, whether they are physical or digital, all writing systems must include some kind of symbol that can be created on a surface. In order to facilitate communication, the writing system's symbols must resemble spoken words or speech.

The greatest advantage of writing is that it gives society a way to regularly and thoroughly preserve information—something that the spoken word could not previously do as successfully. Writing enables communities to communicate knowledge, transmit information, and

stages of development

Sumer

An ancient civilization of southern Mesopotamia, is believed to be the place where written language was first invented around 3200 BCE.

Beginning with the Neolithic pottery phase, when clay tokens were used to keep track of particular quantities of animals or other goods, writing first appeared. These tokens were initially imprinted on the exterior of spherical clay envelopes, which were later used to keep them. Afterwards, flat tablets were gradually introduced in place of the tokens, and signs were recorded using a stylus. Towards the end of the fourth millennium BCE, Uruk was where actual writing was first discovered. Other areas of the Near East quickly followed.

The earliest recorded account of the development of writing is found in a poem from ancient Mesopotamia:

The Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and wrote on it like a tablet because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat the message. It has never been possible to write on clay before.

Enmerkar and the King of Aratta, a Sumerian epic written around 1800 BCE

Although there is agreement among scholars as to the difference between prehistory and the history of early writing, there is disagreement as to when proto-writing became "real writing." The criteria are somewhat arbitrary. In the broadest sense, writing is a way of keeping track of information. It is made up of graphemes, which in turn can be made up of glyphs.

Many centuries of shattered inscriptions typically follow the advent of writing in a particular region. The presence of coherent texts in a culture's writing system is how historians determine a culture's "historicity".

Standard reconstruction of the development of writing. There is a possibility that the Egyptian script was invented independently from the Mesopotamian script.

A conventional "proto-writing to true writing" system follows a general series of developmental stages:

Picture writing system: glyphs (simplified pictures) directly represent objects and concepts. In connection with this, the following substages may be distinguished:

Mnemonic: glyphs primarily as a reminder.

Pictographic: glyphs directly represent an object or a concept such as (A) chronological, (B) notices, (C) communications, (D) totems, titles, and names, (E) religious, (F) customs, (G) historical, and (H) biographical.

Ideographic: graphemes are abstract symbols that directly represent an idea or concept.

Pre-cuneiform tags, with drawing of goat or sheep and number (probably "10"): "Ten goats", Al-Hasakah, 3300–3100 BCE, Uruk culture.

Transitional system: graphemes refer not only to the object or idea that it represents but to its name as well.

Phonetic system: graphemes refer to sounds or spoken symbols, and the form of the grapheme is not related to its meanings. This resolves itself into the following substages:

Verbal: grapheme (logogram) represents a whole word.

Syllabic: grapheme represents a syllable.

Alphabetic: grapheme represents an elementary sound.

Designs on some of the labels or token from Abydos, carbon-dated to circa 3400–3200 BC and among the earliest form of writing in Egypt. They are remarkably similar to contemporary clay tags from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

The best known picture writing system of ideographic or early mnemonic symbols are:

Jiahu symbols, carved on tortoise shells in Jiahu, c. 6600 BCE

Vinča symbols (Tărtăria tablets), c. 5300 BCE[24]

Early Indus script, c. 3100 BCE

In the Old World, true writing systems developed from neolithic writing in the Early Bronze Age (4th millennium BC).

Locations and timeframes

Comparative evolution

from pictograms to abstract shapes, in Mesopotamian cuneiforms, Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters

Proto-writing

The first writing systems of the Early Bronze Age were not a sudden invention. Rather, they were a development based on earlier traditions of symbol systems that cannot be classified as proper writing, but have many of the characteristics of writing. These systems may be described as "proto-writing". They used ideographic or early mnemonic symbols to convey information, but it probably directly contained no natural language. These systems emerged in the early Neolithic period, as early as the 7th millennium BC, and include:

The Jiahu symbols found carved in tortoise shells in 24 Neolithic graves excavated at Jiahu, Henan province, northern China, with radiocarbon dates from the 7th millennium BCE. Most archaeologists consider these not directly linked to the earliest true writing.

Vinča symbols, sometimes called the "Danube script", are a set of symbols found on Neolithic era (6th to 5th millennia BCE) artifacts from the Vinča culture of Central Europe and Southeast Europe.

The Dispilio Tablet of the late 6th millennium may also be an example of proto-writing.

The Indus script, which from 3500 BCE to 1900 BCE was used for extremely short inscriptions.

The Dispilio Tablet

The Dispilio tablet is a wooden tablet bearing inscribed markings, unearthed during George Hourmouziadis's excavations of Dispilio in Greece, and carbon 14-dated to 5202 (± 123) BC.

It was discovered in 1993 in a Neolithic lakeshore settlement that occupied an artificial island near the modern village of Dispilio on Lake Kastoria in Kastoria, Western Macedonia, Greece.

Even after the Neolithic, a number of societies used proto-writing as a transitional form before adopting formal writing. Such a mechanism might have existed in the quipu of the Incas (15th century CE), often known as "talking knots". Another example is the pictographs created by Uyaquk before the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language developed the Yugtun syllabary around 1900.

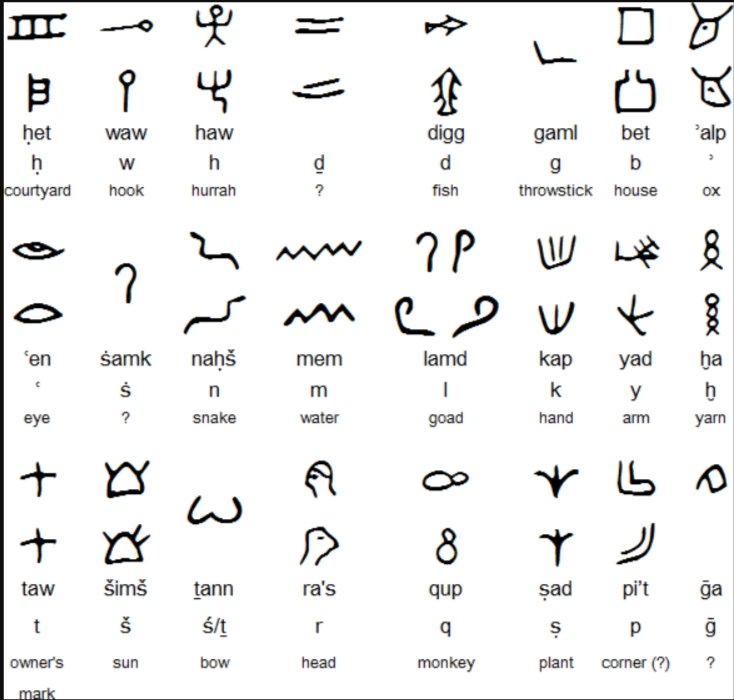

Ancient writing

The Bronze Age saw the development of writing in a wide range of cultures. Indus script, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Cretan hieroglyphs, Chinese logographs, Sumerian cuneiform writing, and the Olmec script of Mesoamerica are a few examples. Around 1600 BCE, the Chinese script most likely evolved apart from the Middle Eastern scripts. It is also generally accepted that the pre-Columbian Mesoamerican writing systems, which include the Olmec and Maya scripts, had separate origins. In 2000 BCE, it is believed that the first real alphabetic writing was created for Hebrew laborers in the Sinai by assigning Semitic values to mostly Egyptian hieratic characters (see History of the alphabet and Proto-Sinaitic alphabet).

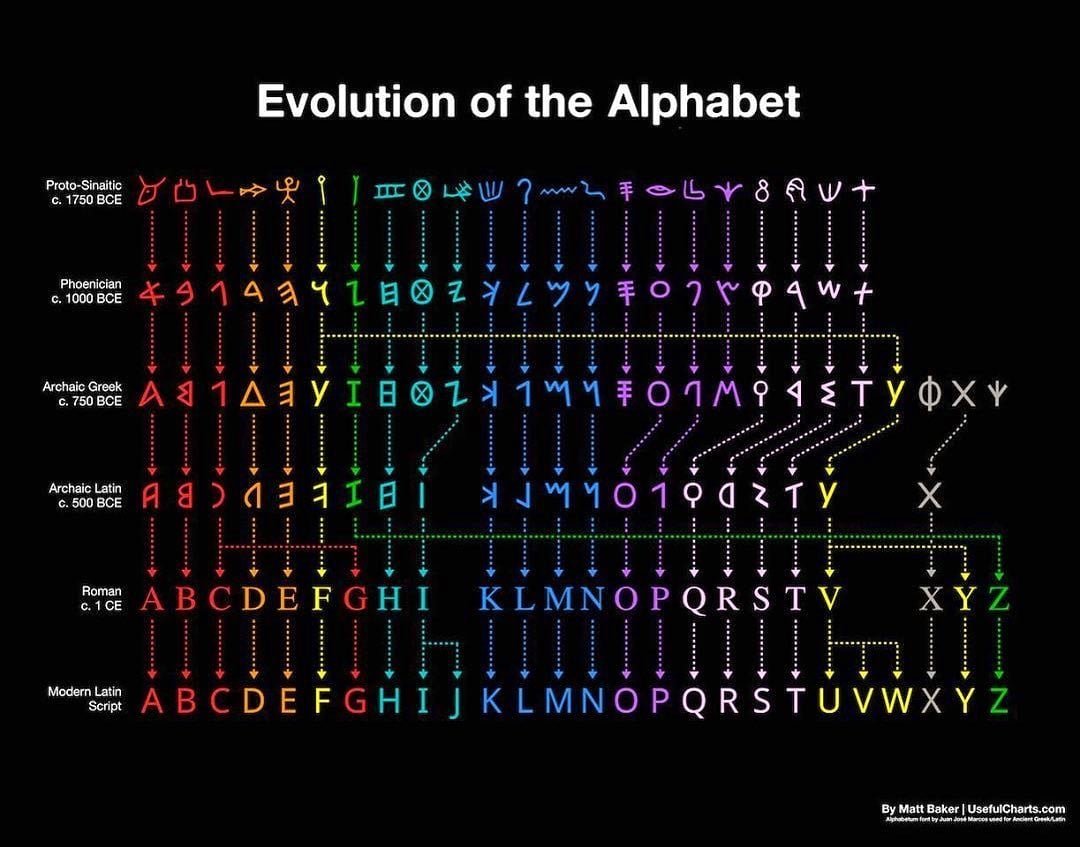

Ethiopia's Geez writing system is regarded as Semitic. With roots in the Meroitic Sudanese ideogram system, it is most likely of semi-independent origin. The majority of alphabets used today are either direct descendants of this one invention, many through the Phoenician alphabet, or were designed in direct response to it. The early Old Italic alphabet and Plautus (c. 750–250 BCE) were separated by around 500 years in Italy, while the Elder Futhark inscriptions and early works like the Abrogans (c. 200–750 CE) are separated by a similar amount of time in the case of the Germanic peoples.

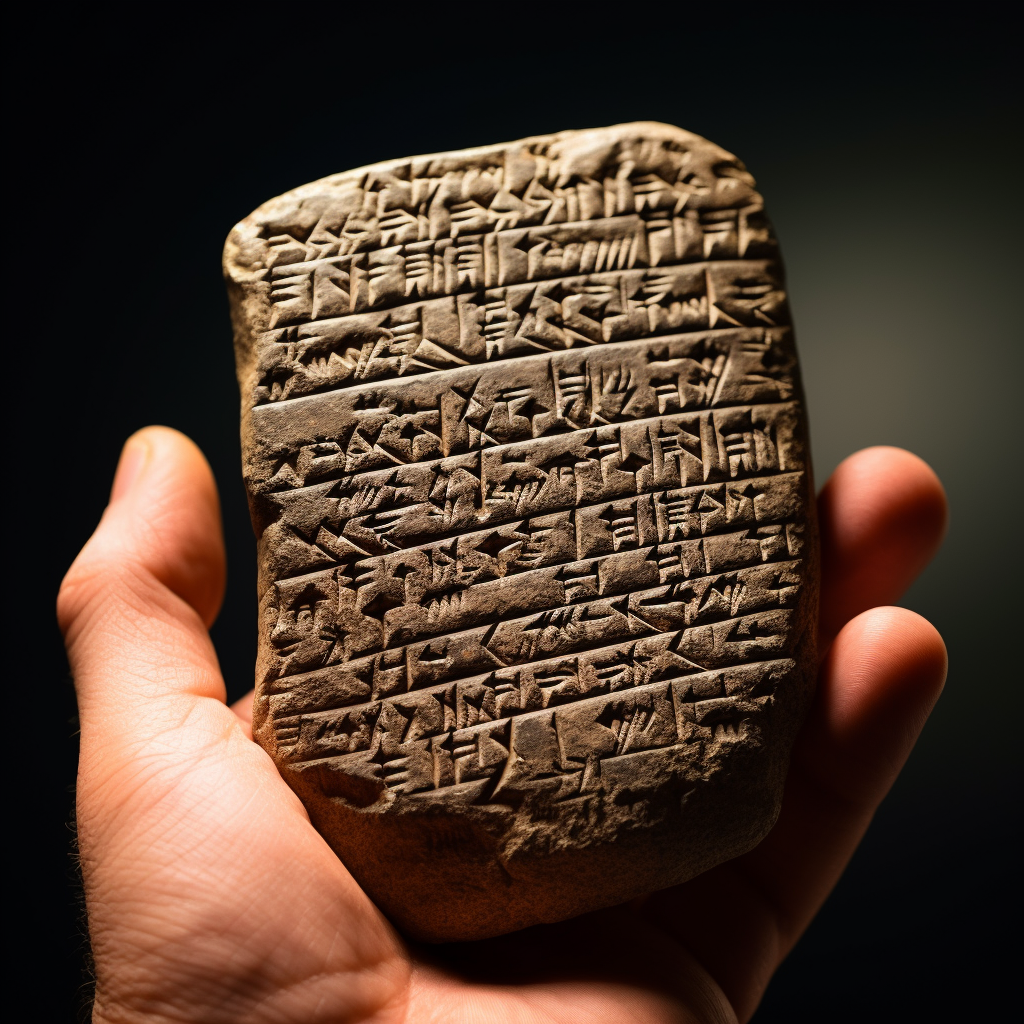

Cuneiform writing

The first Sumerian script was derived from a system of clay tokens used to denote different types of goods. This had developed into a system of keeping accounts by the end of the fourth millennium BC, utilizing a stylus with a circular form that was impressed into soft clay at various angles to record numbers. A pointed stylus was used to gradually add pictographic lettering on this to show what was being counted. Writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the name "cuneiform") began to include phonetic features by the 29th century BCE and gradually replaced writing with a round stylus and a sharp stylus by about 2700–2500 BCE.

Cuneiform first started to represent Sumerian syllables around 2600 BCE. Ultimately, cuneiform writing evolved into a general-purpose system for writing numerals, syllables, and logograms. This alphabet was adapted to the Akkadian language starting in the 26th century BCE, and from there to others like Hurrian and Hittite. This writing system resembles Old Persian and Ugaritic scripts in appearance.

Hieroglyphics from Egypt

Literacy was concentrated among a well-educated elite of scribes, who played a crucial role in upholding the Egyptian empire through writing. To become scribes in the employ of temple, royal (pharaonic), and military authority, one had to come from a certain background.

According to Geoffrey Sampson, the general concept of expressing words from a language in writing was likely transmitted to Egypt via Sumerian Mesopotamia. Egyptian hieroglyphs "came into being a little after Sumerian script, and, possibly [were], invented under the influence of the latter." Despite the significance of early Egypt-Mesopotamia links, "no definitive judgment has been established as to the genesis of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt" due to the lack of direct evidence. However, it is stated and agreed upon that "a very compelling argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt" and that "the evidence for such direct influence remains fragile."

Egyptian writing does suddenly appear at that time, but Mesopotamia has an evolutionary history of sign usage in tokens dating back to around 8000 BCE. Since the 1990s, discoveries of glyphs at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, may challenge the conventional idea that the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one. These glyphs were discovered in tomb U-J at Abydos; they were written on ivory and most likely served as labels for other items discovered there.

Even though he acknowledged that Egypt's geographic location made it a receptacle for many influences, Egyptian scholar Gamal Mokhtar maintained that the inventory of hieroglyphic symbols originated from "fauna and flora used in the signs [which] are essentially African" and that in regards to writing, "we have seen that a purely Nilotic, therefore African origin not only is not excluded, but probably reflects the reality."

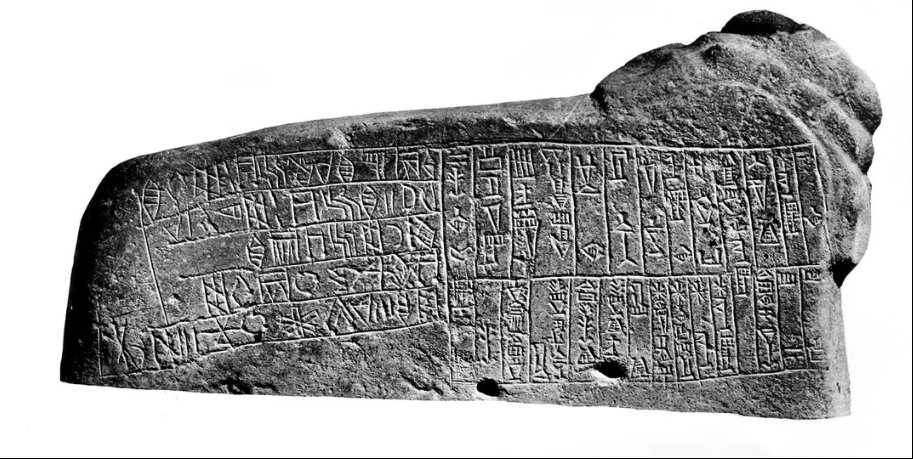

Elamite writing

The unintelligible Proto-Elamite writing first appears around 3100 BCE. Around the latter third millennium, it is thought to have evolved into Linear Elamite, which was later supplanted by Elamite Cuneiform, which was adapted from Akkadian.

Indus script

Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not these symbols constituted a writing system used to record the as yet unidentified language(s) of the Indus Valley civilisation.

The Indus script has been assigned to markings and symbols discovered at numerous Indus Valley civilization sites due to the hypothesis that they were used to transcribe the Harappan language. It is disputed whether the script, which was in use from roughly 3500 to 1900 BCE, is a Bronze Age writing script (logographic-syllabic) or merely proto-writing symbols. According to analysis, it was written in boustrophedon or from right to left.

early SEMITIC ALPHABETS

Around 1800 BCE in Ancient Egypt, the first "abjads," which mapped individual symbols to individual phonemes but not necessarily each phoneme to a symbol, appeared as a representation of the language created there by Semitic workers. However, by that time, alphabetic principles had only a remote chance of being ingrained into Egyptian hieroglyphs for upwards of a millennium.

Did the Proto-Canaanite alphabet take its symbols independently of the hieroglyphs?

It is only until the end of the Bronze Age that the Proto-Sinaitic script separates into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet (c. 1400 BCE), Byblos syllabary, and the South Arabian alphabet (c. 1200 BCE). These early abjads remained of minor significance for several decades. The untranslated Byblos syllabary most likely had some influence on the Proto-Canaanite, which in turn provided inspiration for the Ugaritic alphabet (c. 1300 BCE).

Anatolian hieroglyphs

The Luwian language was written down using Anatolian hieroglyphs, a native hieroglyphic script found in western Anatolia. Around the fourteenth century BCE, it initially appeared on royal seals of the Luwians.

Chinese characters

The corpus of inscriptions on oracle bones and brass from the late Shang dynasty is the earliest authenticated example of the Chinese script that has been found so far. The oldest of these is believed to date from about 1200 BCE.

There have been recent finds of tortoise-shell carvings from around 6000 BCE, such as Jiahu Script and Banpo Script, but it is debatable whether or not the carvings are complex enough to be considered writing. 3,172 cliff carvings from the period between 6000 and 5000 BCE have been found near Damaidi in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. They contain 8,453 different characters, including images of the sun, moon, stars, gods, and scenes of grazing or hunting.

Replica

of ancient Chinese script on an oracle turtle shell

These pictographs are thought to resemble the first Chinese characters that have been confirmed to be written. Writing in China would predate Mesopotamian cuneiform, traditionally recognized as the first manifestation of writing, by about 2,000 years if it were to be considered a written language. However, it is more likely that the inscriptions represent a type of proto-writing, comparable to the modern European Vinca script.

Early Greek and Cretan scripts

Cretan relics include hieroglyphic writing (early-to-mid-2nd millennium BCE, MM I to MM III, overlapping with Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). The Mycenaean Greek writing system, Linear B, has been decoded, but Linear A has not yet been. The three overlapping, but distinct, Aegean pre-alphabetic writing systems can be categorized according to their chronological order and geographic distribution as follows:

Cretan Hieroglyphic / Crete (eastward from the Knossos-Phaistos axis) / c. 2100−1700 BCE

Linear A / Crete (except extreme southwest), Aegean Islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), Greek mainland (Laconia) and west Minor Asia (Miletus and maybe Troy) / c. 1800−1450 BCE

Linear B / Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) / c. 1450−1200 BCE

The archaeological finds with signs of pre-alphabetic scripts in the Aegean

(Up) The finds with signs of Linear B script reach about 6,000 and constitute the majority of the pre-alphabetic written monuments of the Aegean.

(Middle) About 1,400 are the finds which imprint Linear A and make up a 11% of all pre-alphabetic inscriptions.

(Down) Cretan hieroglyphics occupies 2% of the available finds with only 400 finds.

Illustration: Dimosthenis Vasiloudis

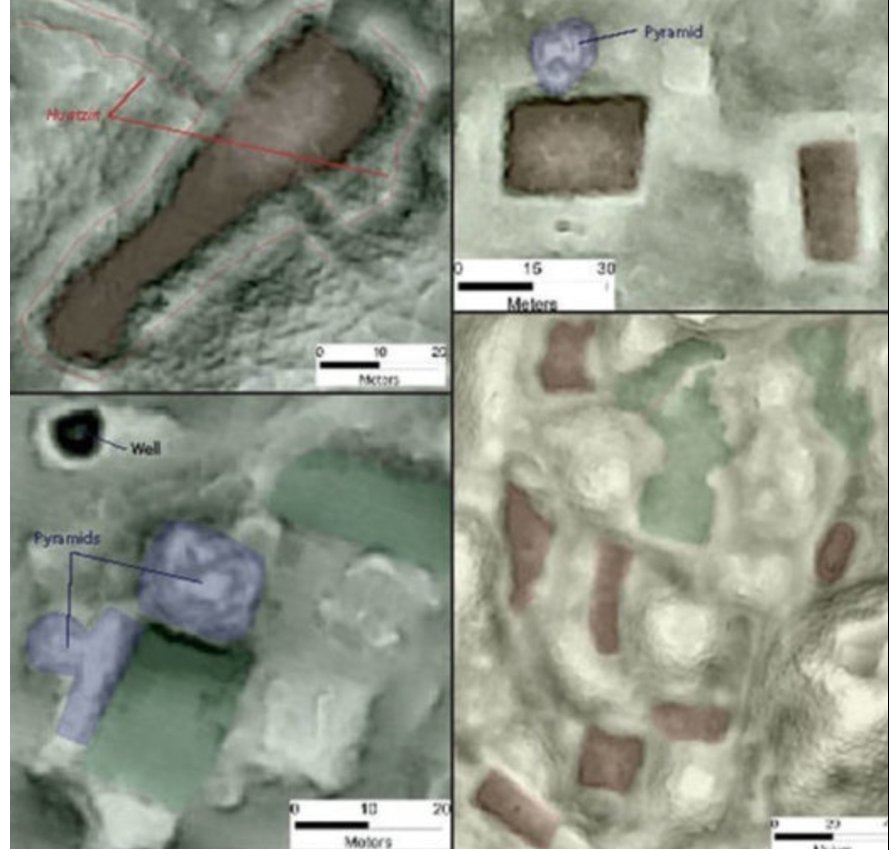

Mesoamerica

The Cascajal Block, a stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing that predates the first Zapotec writing from around 500 BCE, was found in the Mexican state of Veracruz. It is an example of the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere.

Stela 12 and 13

from the southern end of Building L, in the Zapotec city of Monte Albán, Outside of Oaxaca, Mexico.

The Maya script is one of numerous pre-Columbian scripts found in Mesoamerica, and it appears to have been the most well-developed and extensively deciphered. The earliest clearly identifiable Maya inscriptions date to the third century BCE, and writing continued to be used until just before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century BCE. A combination of logograms and syllabic symbols, utilized in Maya writing, is somewhat reminiscent of current Japanese writing.

IRON AGE WRITING

The Proto-Canaanite alphabet, which was used into the Iron Age, is all that the Phoenician alphabet is (conventionally taken from a cut-off date of 1050 BCE). The Greek and Aramaic alphabets were derived from this alphabet. They eventually gave rise to the writing systems that are currently used everywhere, from Western Asia to Africa and Europe. The Greek alphabet, on the other hand, was the first to use specific symbols to represent vowel sounds.

By Matt Baker

In the first centuries of the Common Era, the Greek and Latin alphabets gave rise to a number of European scripts, including the Runes, Gothic, and Cyrillic alphabets, while the Aramaic alphabet developed into the Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac abjads, the latter of which spread as far as Mongolian script. The Ge'ez abugida originated from the South Arabian alphabet. According to some academics, the Indian Brahmic family also descended from the Aramaic alphabet.

GRAKLIANI HILL WRITING

At Georgia's Grakliani Hill, behind a fallen altar from a temple dedicated to a fertility goddess from the seventh century BCE, an obscure script was uncovered in 2015. Grakliani's other temples' inscriptions, which depict animals, people, or decorative features, are different from these ones. Although its letters are rumored to be connected to ancient Greek and Aramaic, the script has no similarities to any known alphabet. In contrast, the earliest Armenian and Georgian letters come from the fifth century CE, right after the respective nations converted to Christianity. The inscription looks to be the oldest local alphabet ever uncovered in the entire Caucasus region. An portion of the inscription measuring 31 by 3 inches had been unearthed by September 2015.

Grakliani script on the basement of altar of goddess of fertility (XI-X c. BC)

Vakhtang Licheli, director of the State University's Institute of Archaeology, claims that "The writings on the temple's two altars have been kept in remarkably good condition. While the pedestal of the second altar is entirely covered with writings, the first altar has few clay letters carved into it." Unpaid students made the discovery. Inscriptions from Grakliani Hill were sent to Miami Laboratory in 2016 for beta analytic radiocarbon dating, which revealed that they were created between c. 1005 and c. 950 BCE.

WRITING IN THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD

When the Greeks adopted the Phoenician script for use with their own language in the early eighth century BCE, the history of the Greek alphabet officially began. The Greek and Phoenician alphabets share a lot of similarities in terms of their characters, and both alphabets nowadays are written in the same order. The Phoenician system's adapter(s) added three letters to the conclusion of the series, known as the "supplementals." The Greek alphabet evolved into a number of different forms.

Early Greek alphabet on pottery in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

One was utilized in southern Italy and west of Athens and is known as Western Greek or Chalcidian. The other variant, known as Eastern Greek, was spoken by the Athenians and in modern-day Turkey before spreading over the rest of the Greek-speaking world. The Greeks initially elected to write like the Phoenicians, from right to left, but subsequently switched to left to right. The lines would then alternately read from left to right, then from right to left, and so on. On occasion, though, the writer would begin the next line where the preceding one ended. Up until the sixth century, this style of writing, called "boustrophedon," mirrored the course of an ox-drawn plough.

Italic scripts and Latin

Cippus Perusinus

Etruscan writing near Perugia, Italy, the precursor of the Latin alphabet

All of the contemporary European scripts have their roots in Greek. The Latin alphabet, named after the Latins, a central Italian people who came to rule Europe with the emergence of Rome, is the most widely used descendant of the Greek script. Around the fifth century BCE, the Etruscan civilization, which employed a multitude of Italic scripts descended from the western Greeks, taught the Romans how to write. The other Old Italic scripts have not survived in very large quantities due to the cultural hegemony of the Roman state, and the Etruscan language is largely extinct.

WRITING DURING THE MIDDLE AGES

Roman rule in Western Europe fell apart, and the Persian Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire became the main centers of literary development. Latin, which was never a major literary language, lost prominence quickly (except within the Roman Catholic Church). Greek and Persian were the two main literary languages, but Syriac and Coptic were also significant.

Arabic quickly became a significant literary language in the area as a result of the development of Islam in the 7th century. Greek's status as a scholarly language soon lost ground to Arabic and Persian. The Turkish and Persian languages now use Arabic script as their principal writing system. The development of the cursive scripts for Greek, the Slavic languages, Latin, and other languages was also greatly inspired by this script.

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system was also extended throughout Europe thanks to the Arabic language. The modern Spanish city of Cordoba had emerged as one of the world's leading intellectual hubs by the start of the second millennium and was home to the largest library at the time. Its location at the meeting point of the Islamic and Western Christian worlds encouraged intellectual growth and written exchange between the two cultures.

THE MODERN ERA AND THE RENAISSANCE

By the 14th century, Western Europe had experienced a renaissance, which had temporarily increased the significance of Greek while slowly restoring Latin's status as an important literary language. In Eastern Europe, particularly in Russia, a comparable but smaller emergence took place. As the Islamic Golden Era came to an end, Arabic and Persian also started to slowly lose ground. In order to codify the phonologies of the various languages, the Latin alphabet underwent several alterations as a result of the rebirth of literary development in Western Europe.

Writing has undergone steady change throughout history, in large part because of the emergence of new technologies. Technology advancements such as the printing press, computer, mobile phone, and pen have all changed how and what is written as well as the medium in which it is generated. Characters can now be generated with a button press rather than a hand motion, especially with the development of digital technology like the computer and the smartphone.