There are two kinds of facts and artifacts that historians and archaeologists can discover. There are those that support the official narrative of history, and those that challenge it. While the second category is more troubling for historians, we must accept those discoveries for what they are and celebrate them when they appear. That's what this video is - a celebration of discoveries that might change history!

11,000 Years OLDER than Göbekli Tepe: 23,000-Year-Old Settlement & Early Cultivation?!

Explore the hidden marvel of Ohalo II, an archaeological gem nestled on the southwestern shore of the Sea of Galilee in Northern Israel. Despite its profound significance, this ancient site remains obscure to many.

Dating back an astonishing 23,000 years to the Last Glacial Maximum, Ohalo II stands as a testament to the enduring resilience of early human societies. Unlike typical seasonal camps, this settlement was inhabited year-round, spanning numerous generations—an exceptional rarity for such antiquity.

Yet, it's not just its age that captivates scholars and enthusiasts alike. Ohalo II boasts two extraordinary claims to fame, earning it a place in the annals of human history.

Firstly, it boasts the world's oldest brush dwellings, offering a glimpse into the daily lives of our distant ancestors. Moreover, and perhaps most remarkably, it presents evidence of the earliest known small-scale plant cultivation—a groundbreaking discovery predating the advent of agriculture in the famed Fertile Crescent by a staggering 11,000 years.

Delve into the profound implications of Ohalo II's revelations by watching our video, unveiling a settlement that predates even Göbeklitepe, and sheds light on the dawn of ice age farming—the very roots of civilization.

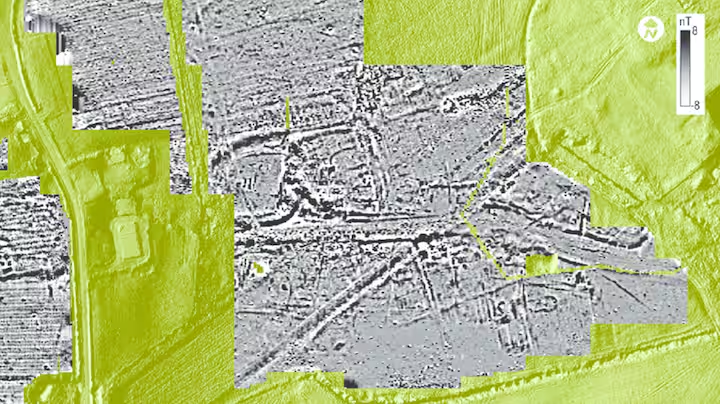

The discovery was made possible by LiDAR technology

Archaeologists find buildings that might have been used as 'Paths for the Dead.'

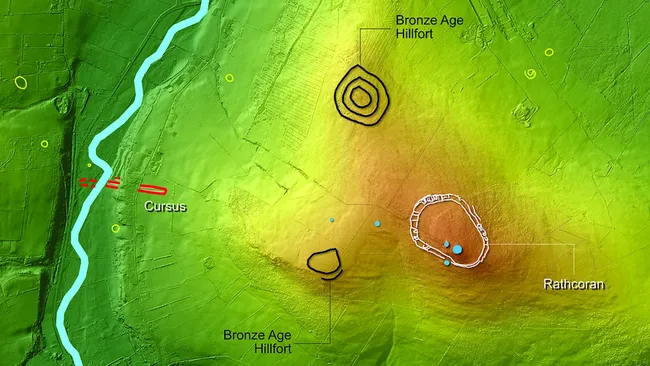

In a remarkable archaeological revelation, recent excavations in Baltinglass, County Wicklow, Ireland, led by Dr. James O'Driscoll of the University of Aberdeen, have brought to light what are believed to be ancient pathways for the deceased.

Employing cutting-edge Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology, which utilizes lasers to meticulously map terrain and uncover concealed structures, researchers have uncovered five monumental structures dating back to the middle Neolithic era, spanning from 8000 BCE to 2000 BCE.

The unearthed constructions, referred to as cursus monuments, comprise earthworks consisting of elongated trenches or ditches that traverse the landscape. Ranging in size from 122 to over 183 meters in length, with the most extensive stretching to 400 meters, these monuments are thought to have served as ceremonial avenues for mourning rituals or the journey of the departed into the afterlife.

Lidar imaging of one of the five curus monuments (seen in red) found at the prehistoric site in Ireland. (Image credit: James O'Driscoll; Antiquity Publications Ltd)

Dr. O'Driscoll postulates that the alignment of these sites with the morning sun during the summer solstice, coupled with their proximity to other ancient burial grounds, lends credence to the theory of their ceremonial significance.

The pivotal role of LiDAR technology cannot be overstated in this groundbreaking discovery. By deploying airborne laser pulses to survey the terrain, researchers were able to discern structures characteristic of cursus monuments. Notably, an Irish aerial survey company conducted a LiDAR scan of the area in 2022, revealing not only the cursus monuments but also previously unknown features such as a Bronze Age hillfort and medieval ringforts.

The significance of these findings extends beyond mere archaeological curiosity. The cluster of cursus monuments discovered in Baltinglass is believed to be the most extensive in both Ireland and Britain, challenging long-held assumptions about the region's historical narrative. Contrary to prior beliefs suggesting a 2000-year desertion of the area between the Early Neolithic and Late Bronze Age, these discoveries hint at a more continuous habitation and a deeper entanglement of daily life, agriculture, and spiritual beliefs in ancient societies.

In essence, these revelations offer profound insights into the complex cultural and spiritual practices of Neolithic and Bronze Age communities, reshaping our understanding of Ireland's ancient past and its enduring legacy in the landscape of County Wicklow.

New study links ancient Egyptian tombs to radioactive waste, revealing insights into the "Pharaoh's curse."

A new study suggests that ancient Egyptians may have experimented with nuclear technology, linking the "Pharaoh's curse" to buried radioactive nuclear waste found in tombs.

The burial mask of Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun

(Image:Getty Images)

Recent research delves into the enigmatic "Pharaoh's Curse" that seemed to afflict those who dared to disturb the sanctity of ancient Egyptian tombs. This study, featured in the Journal of Archaeological Science, overturns conventional wisdom by proposing a provocative theory: the curse may have been linked to the inadvertent exposure to radioactive nuclear waste stored within these ancient burial sites.

The investigation draws a striking parallel between ancient Egyptian texts and nuclear technology, suggesting a level of scientific sophistication previously unrecognized. Texts dating back to 2300-2100 BC, such as the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, contain references to transformative processes reminiscent of uranium-based materials. For instance, descriptions of Osiris as being "transformed into light" hint at an understanding of nuclear energy release and matter-energy conversion.

Moreover, symbolic references to substances like "saffron cakes" evoke uranium-related materials, implying an early awareness or utilization of radioactive elements. Intriguingly, archaeological evidence indicates rituals involving the burial of "hated excrements" in underground vaults, possibly reflecting an early grasp of radioactive waste disposal methods.

The study also examines the layout of Egyptian tombs, proposing that the unnatural radiation detected within these structures aligns with patterns consistent with nuclear waste storage. Symbolic motifs found on stone pots, representing different types of radiation, suggest an awareness of the dangers associated with radiation exposure.

Furthermore, textual references to the processing of "magic food" using advanced techniques like diffusion and centrifugation hint at a sophisticated understanding of material refinement processes akin to nuclear technology. The study contends that these findings challenge traditional explanations of the "Pharaoh's curse," suggesting instead a connection to the presence of radioactive materials within the tombs.

Supporting this hypothesis are historical accounts of researchers involved in tomb excavations experiencing unusually high rates of cancer-related deaths and other symptoms consistent with radiation sickness. Notable figures, such as Lord Carnarvon and Arthur Weigall, whose lives were intertwined with the exploration of Tutankhamun's tomb, succumbed to untimely deaths following exposure to these tombs.

While Howard Carter, the lead archaeologist behind the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb, did not meet the same fate, the study underscores the pervasive risk posed by the inadvertent exposure to radioactive elements within these ancient burial sites. Thus, the "Pharaoh's curse" takes on a new dimension, intertwined with the mysteries of nuclear technology and ancient Egyptian civilization.

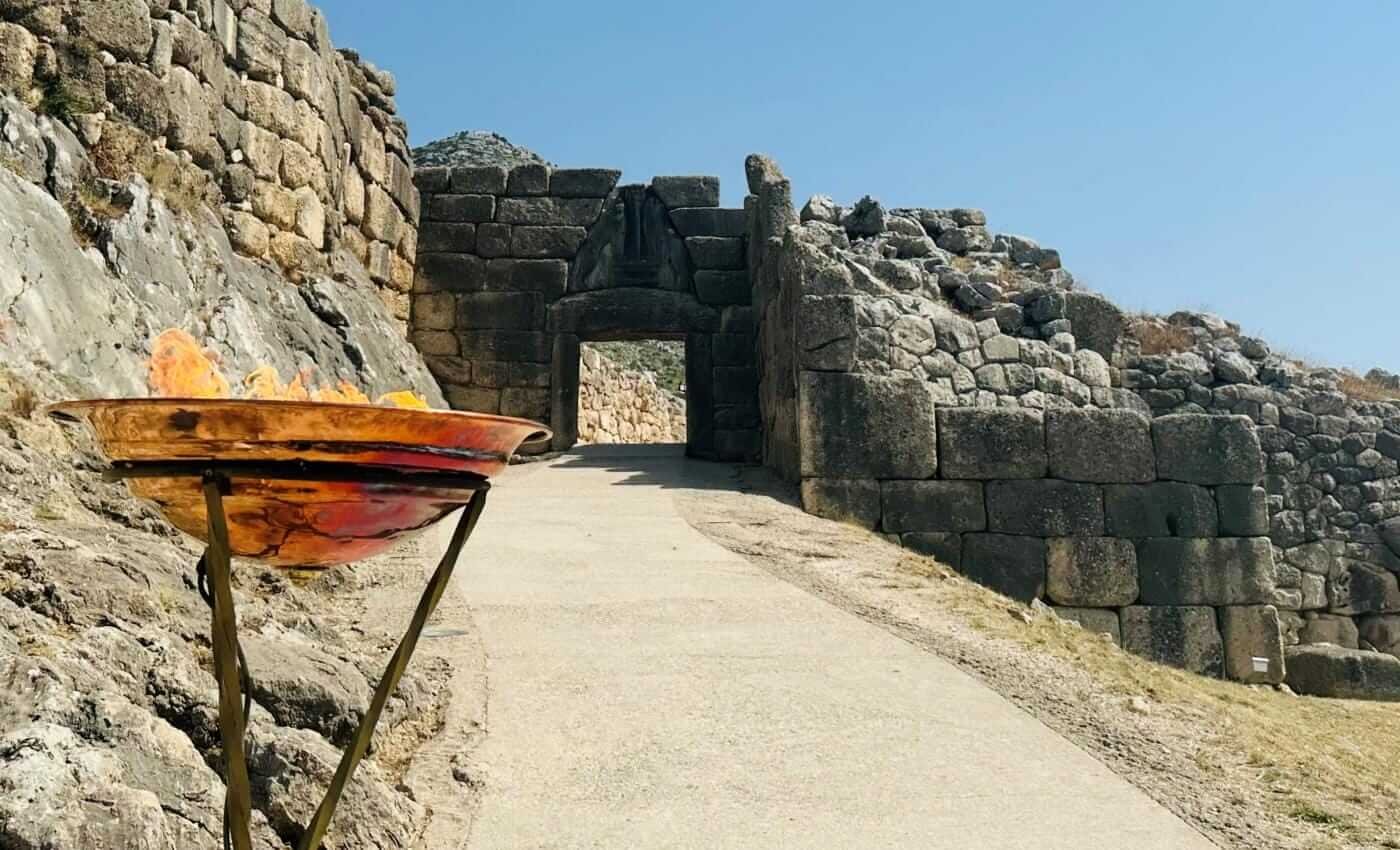

In the Footsteps of History: The Olympic Flame's 11-Day Cultural Sojourn Through Greece for Paris 2024

Embarking on an 11-day odyssey rich in history and cultural significance, the Olympic Flame for the Paris 2024 Games traversed the storied landscapes of Greece, connecting the modern spectacle with its ancient origins. This ceremonial pilgrimage not only symbolizes the enduring spirit of the games but also casts light on Greece's unparalleled contributions to history, archaeology, and the very concept of the Olympics.

Ancient Olympia: The journey commenced at the heart of the ancient Olympic Games, where athletes once vied for glory and honor under the gaze of the gods. Today, the Flame’s ignition at this sacred site serves as a poignant tribute to the enduring legacy of the games, illuminating the ruins with the promise of peace and camaraderie that the modern games aspire to embody.

Statue of Asclepius, Trikala: The flame then cast its glow upon the effigy of Asclepius, enshrining the ancient commitment to healing and the arts. Amidst a city known for its medieval architecture and Byzantine heritage and also for being, during prehistoric ages, an important cultural center since it was the birthplace of Asclepius, this stop on the Flame's journey bridges the worlds of ancient myth and the enduring human quest for knowledge and well-being.

Mycenae: The hallowed grounds of Mycenae, a citadel that whispers tales of kings and epic sagas, provided a dramatic backdrop for the Flame. Here, amidst the Cyclopean walls and Lion Gate, the Flame's passage echoes the heroic spirit that has captured imaginations for millennia.

Sounio, Temple of Poseidon: Perched at the edge of the Aegean, the Temple of Poseidon at Sounio stands as a sentinel to seafarers. The Olympic Flame, alight against the columns, paid homage to the god of the seas, a reminder of the ancient Greeks' reverence for the elemental powers that shaped their world.

Ancient Oracle of Delphi: The Flame's ascent to Delphi carried it through the misty realms of prophecy and divine will. Here, at the navel of the ancient world, it was as if Pythia herself might have presaged the uniting force of the Flame, a beacon of hope and a call to the world’s athletes to gather once more.

Naxos Island, Remains of the Temple of Apollo: On the Isle of Naxos, amid the scattered remnants of Apollo’s temple (known as Portara), the Flame stood as a testament to the light of knowledge and music, central themes in the legacy of the god it honored. The Flame's journey across the island highlighted the blend of natural beauty and human artistry that typifies the Greek landscape.

Parthenon, Athens: No journey would be complete without the Flame basking in the glory of the Parthenon. Here, democracy took its first steps, and art and philosophy found their highest expression. The flame's reflection on the Parthenon's marbles serves as a metaphor for the light of ancient Greece, continually inspiring humanity's pursuit of excellence.

Macedonian Royal Tombs of Aigai-Vergina: Finally, the Flame visited the solemn grandeur of the Macedonian Royal Tombs at Aigai-Vergina, where the legacies of kings and conquerors lay enshrined. In the quietude of these ancient halls, the flame's passage seemed to whisper of the vast narratives of history that continue to shape our modern world.

The Aqueduct of Kavala, Kamares: As the Flame traced the path of water through the Kamares, the grandeur of the Aqueduct of Kavala stood as a testament to the ingenuity and architectural prowess of the ancients. The stark arches and the steadfastness of this structure remind us that the flow of progress, like water, is ceaseless. Here, the Flame not only celebrated human achievement but also underscored the vital connection between past civilizations and their surrounding environments, offering a moment of reflection on the endurance of human creation.

Ancient City of Corinth: Journeying next to the crossroads of Peloponnesian commerce and culture, the Flame visited the storied city of Corinth. With its temples, fountains, and the imposing Acrocorinth fortress, the city's ruins tell a tale of a once-thriving hub that connected ancient societies. The flame, dancing among these relics, symbolized the eternal bridge between the ancient cosmopolitan spirit and the global community the Olympic Games aim to foster.

First Ancient Theatre of Larissa, Greece: Finally, the Flame illuminated the First Ancient Theatre of Larissa, a cultural landmark nestled at the heart of Thessaly. This theatre, carved into the hillside, once echoed with the voices of poets and the applause of spectators. As the flame's glow cast shadows on the stone tiers, it evoked the timeless importance of art and community. Here, the spirit of the games, much like the dramas of old, reflects the spectrum of human experience, from the tragic to the triumphant, all within the amphitheater of history.

From the sanctuaries of the gods to the heights of human achievement, the Olympic Flame’s journey through Greece for "Paris 2024" intertwines the threads of the past with the aspirations of the present, heralding the upcoming celebration of unity, competition, and peace that the Olympic Games represent.

From Thule to the Tropics: The Sea-Faring Reach of Ancient Greek Explorers

The Legacy of Greek Maritime Pioneers: The Widespread Maritime Exploration of the Greeks

In the annals of ancient history, few narratives are as enthralling as those of the Greek mariners, whose sails billowed on the winds of discovery and curiosity. Their intrepid voyages not only charted the physical expanses of the seas but also the unbounded potential of human endeavor. This article delves into the odysseys of six pioneering Greek explorers, whose contributions are immortalized through the fragments of history that have endured the passage of time.

Pytheas of Massalia: The Northern Voyager

In the 4th century BC, Pytheas embarked on a journey from the Greek colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille) that would etch his name into the lore of explorers. His daring voyage to the British Isles and possibly beyond to Thule—a land shrouded in the mists of legend, thought to lie in the icy embrace of the far North—stands as a testament to his audacious spirit. The accounts of Pytheas's travels reach us through the writings of Strabo, Pliny, and Diodorus, piecing together a tale of a world far from the Mediterranean warmth, where the sun scarcely dipped below the horizon.

Strabo adds the following in Book 5: “Now Pytheas of Massilia tells us that Thule, the most northerly of the Britannic Islands, is farthest north, and that there the circle of the summer tropic is the same as the Arctic Circle”

Euthymenes of Massalia: The African Enigma

A contemporary to Pytheas, Euthymenes set his sights southward, skirting the edges of the African continent beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Though details are sparse, Strabo's geographical treatises convey images of a coast that extended into unknown territories, a narrative that challenged the Greek understanding of the world's peripheries. Euthymenes's legacy is that of a pioneer who peeled back the veil on Africa's western seaboard, long before the exploits of later Hellenistic and Roman explorers.

Eudoxus of Cyzicus: A Dream Unfulfilled

In a bid that would presage the efforts of much later adventurers, Eudoxus of Cyzicus dared to dream of a sea route around Africa. Strabo and Pliny relay his multiple attempts, although success ultimately eluded him.

After completing a pair of triumphant expeditions to India via the Red Sea under the patronage of the Egyptian ruler Ptolemy Euergetes II, the intrepid navigator set sail for Gades, known today as Cádiz in Spain. It was there that he meticulously prepared three vessels for his ambitious goal of circumnavigating the continent. Unfortunately, his inaugural voyage met with misfortune as his ship ran aground off the southern coast of Morocco. Undeterred, he embarked once more, navigating the western fringe of Africa, but this time, the sea claimed the entirety of his brave crew.

The dream of circumventing Africa's southern tip lay dormant, unchallenged again, until the dawn of the late 15th century. His ventures in the 2nd century BC served as crucial precursors to the understanding of Africa's maritime contours, a puzzle that would not be completely solved until the Age of Discovery.

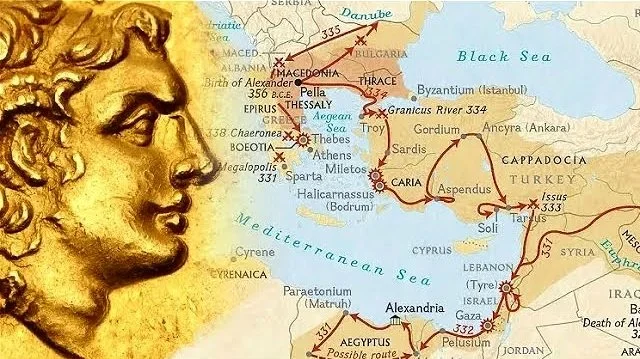

Onesicritus of Astypalaia: The Fleet of the Great Alexander

Onesicritus, chronicled by Arrian and Strabo, wielded his maritime acumen in service of Alexander the Great. His voyages, particularly through the Indian Ocean, expanded the ambit of Hellenic knowledge and exemplified the fusion of exploration and empire. As Alexander's fleet commander, Onesicritus not only traversed unknown waters but also brought back accounts that would feed the Greek appetite for the wonders of the East.

The documented extent of ancient Greek exploration by sea

Source of the map: Twitter/Philoveritas

Megasthenes: The Chronicler of India

As an envoy to the Mauryan court of Chandragupta, Megasthenes's "Indica" offered the Greeks a vivid, albeit second-hand, portrait of the Indian subcontinent. His descriptions of India, though not without exaggeration, provided a mosaic of its geography, flora, fauna, and social structures. The fragments of his work, preserved in the citations of later historians, form a crucial bridge between Greek and Indian civilizations.

Nearchus: The Return from the Indus

Perhaps one of the most celebrated naval voyages of antiquity was that of Nearchus, who navigated from the mouth of the Indus River back to the Persian Gulf. Under the aegis of Alexander, Nearchus’s expedition, meticulously recounted by Arrian in "Indica," was as much a military retreat as a voyage of discovery. While his own writings are lost to time, the accounts passed down underscore the challenges and triumphs of his momentous journey.

These maritime odysseys are more than mere footnotes in history; they are enduring symbols of the Hellenic quest for knowledge and the unrelenting human drive to uncover the Earth's mysteries. With the help of starlight and ambition, the ancient Greek explorers set sail for the unknown, leaving behind a legacy that has continued to whisper to us over the centuries, encouraging us to pursue our own discoveries.

This "revenant" grave was uncovered at a site near Oppin in the German state of Saxony-Anhalt. The deceased man was buried with a large stone on his legs, possibly to prevent him from returning to life, according to archaeologists.

© ANJA LOCHNER-RECHTA/STATE OFFICE FOR MONUMENT PRESERVATION AND ARCHEOLOGY SAXONY-ANHALT

Archaeologists uncover graves of ancient people believed to be zombies and intentionally buried to ensure they never rise again.

Archaeologists have recently made a striking discovery in Germany, unearthing an ancient burial site near the village of Oppin in the state of Saxony-Anhalt. This find sheds light on intriguing burial practices of prehistoric peoples, revealing a profound fear of the dead returning to life.

The burial site in question is no ordinary grave; it represents what archaeologists refer to as a "revenant" grave, a term borrowed from folklore describing individuals who return from the dead, either as spirits or animated corpses, often to haunt or menace the living. These graves, colloquially dubbed "zombie" graves, have been found across Europe, dating back thousands of years.

What sets these graves apart are the precautions taken by ancient communities to prevent the deceased from rising again. In the case of the German burial, a man aged between 40 to 60 years old was found in a crouched position, with a sizable stone—measuring approximately 3.2 feet in length and 1.6 feet wide—placed over his legs. Archaeologists speculate that this stone was intentionally positioned to weigh down the body, possibly to thwart any attempt at resurrection.

This fear of the dead transcends epochs and cultures. Even in the Stone Age, people sought to ward off the return of the deceased through rituals and magical practices. Susanne Friederich, an archaeologist involved in the excavation, explains that ancient beliefs held that the dead might attempt to claw their way out of their graves, hence some were buried face down, as if to thwart their ascent to the surface.

The burial site dates back around 4,200 years, the archaeologist said. Photo: © LDA Saxony-Anhalt, Anja Lochner-Rechta

While the exact dating of the grave is yet to be determined, it appears to be associated with the Bell Beaker culture, which emerged over 4,500 years ago in Europe. This find is particularly significant as it could represent the first revenant grave from the Bell Beaker period discovered in central Germany. Such a discovery is rare, given the limited evidence of such burial customs within this culture.

Beyond the revenant grave, the excavation unearthed further artifacts, including another grave from the Bell Beaker culture and remnants of a hearth, providing valuable insights into the daily lives and beliefs of ancient peoples. This discovery underscores the enduring fascination with death and the afterlife, offering a glimpse into the fears and rituals of our distant ancestors.

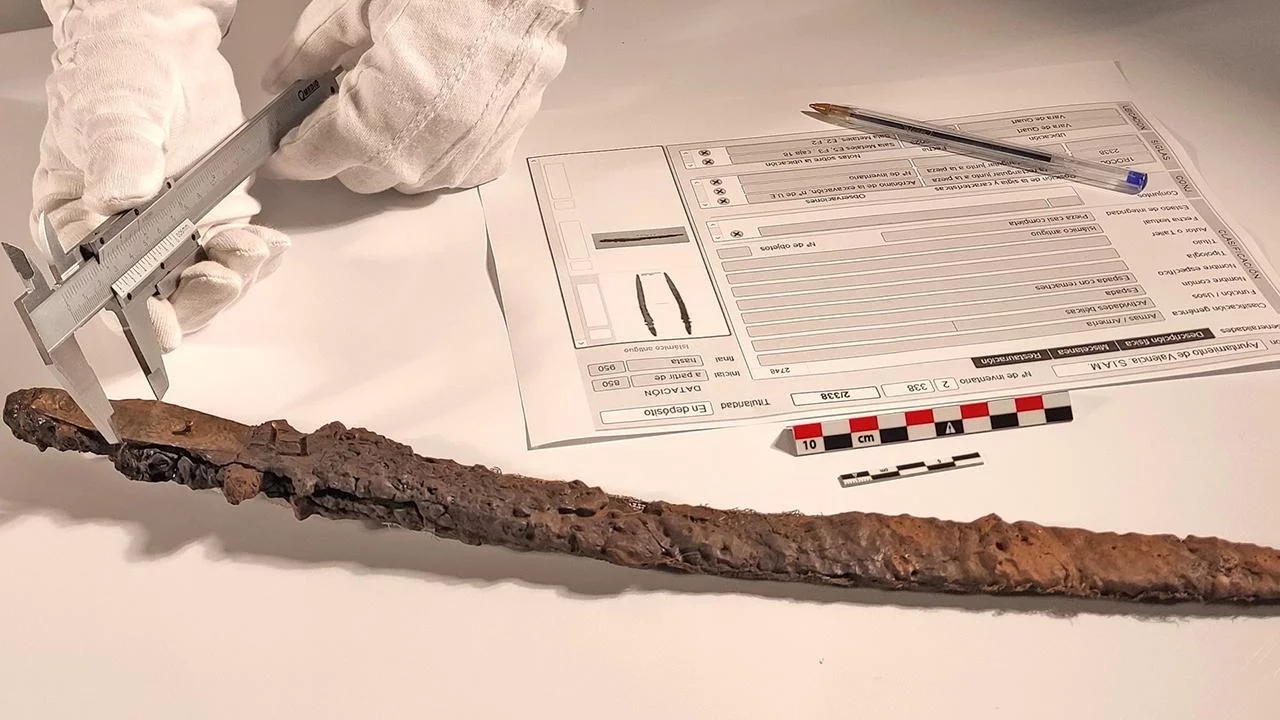

The sword unearthed in Valencia in 1994 dates back 1,000 years. Credit: Valencia City Council Archaeology Service (SIAM)

Spanish Archaeologists Unravel Secrets of Iconic 'Excalibur' Sword

In a captivating discovery reminiscent of Arthurian legend, archaeologists unearthed a remarkable artifact in Valencia, Spain—an iron sword named "Excalibur." The sword, found standing upright in the earth in 1994 at an archaeological site near Valencia's ancient Roman Forum, has now yielded its secrets as researchers unveil its storied past.

Named after the fabled sword of King Arthur, Excalibur's initial discovery sparked intrigue and speculation about its origins and significance. Situated in a region steeped in history, the site of Valencia's old town has seen the rise and fall of numerous civilizations over the centuries.

After decades of uncertainty surrounding its age, the Valencia City Council's Archeology Service (SIAM) has successfully dated Excalibur to the 10th century, placing it squarely within the Islamic era of Spain, known as Al-Andalus. This period, stretching from A.D. 711 to 1492, marked a significant chapter in the Iberian Peninsula's history, characterized by the coexistence of Islamic and Christian cultures.

Excalibur's dating marks a milestone as the first Islamic-era sword discovered in Valencia, shedding light on a period of history previously obscured. Swords from this era are rare finds, particularly in Valencia, where challenging soil conditions pose obstacles to preservation efforts.

Measuring approximately 18 inches in length, Excalibur boasts a distinctive design, with a hilt adorned with bronze plates and a moderately sized blade that gently curves towards the tip. This curvature, once a source of confusion regarding its age, distinguishes it from Visigoth swords of similar appearance.

The Visigoths, a prominent Germanic tribe, exerted influence across Europe during the twilight of the Western Roman Empire and the Early Middle Ages. In the Iberian Peninsula, they established a powerful kingdom until the Islamic conquest reshaped the region.

Despite its resemblance to Visigoth swords, Excalibur's unique characteristics, coupled with analysis of sediment layers, allowed researchers to confirm its Islamic-era origins. Its size and lack of handguard suggest it may have been wielded by a mounted warrior, adding another layer to its historical significance.

"This sword's distinct design imbues it with tremendous archaeological and cultural value," remarked José Luis Moreno, Valencia's councilor for cultural action, heritage, and cultural resources. With Excalibur restored to its former glory, its legacy as a tangible link to Valencia's rich past continues to captivate imaginations and illuminate history's mysteries.

A scientist claims to have cracked the case of the 'Pharaoh's curse' that was believed to have killed more than 20 people who opened King Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922. Pictured is Howard Carter who was long said to die from the curse

Scientist Unveils True Cause of 'Pharaoh's Curse' Linked to King Tut's Tomb

The enigmatic 'Pharaoh's curse,' long believed to have claimed over 20 lives following the opening of King Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922, has finally been deciphered by a determined scientist. Ross Fellowes contends that behind the veil of superstition lies a concrete biological explanation.

Contrary to the ancient Egyptian texts warning of a mysterious affliction, Fellowes posits that the fatalities were a result of radiation poisoning, stemming from deliberate placement of uranium-laden natural elements and toxic substances within the sealed confines of the tomb.

The revelation sheds light on the demise of individuals like Howard Carter, the pioneering archaeologist who succumbed to cancer, possibly induced by radiation exposure. Lord Carnarvon, another figure associated with the tomb's opening, met his end due to blood poisoning from a mosquito bite.

The scientific breakthrough not only demystifies the 'curse' but underscores a deliberate, albeit ancient, form of foul play. It dismantles the notion of supernatural retribution perpetuated by some Egyptologists, offering a sobering look at the perils lurking within the confines of ancient burial sites.

King Tutankhamun, the iconic figure at the heart of the mystery, continues to intrigue with his untimely demise at around 18 years old. Despite his illustrious lineage, Tutankhamun's life was marred by health issues, potentially stemming from familial intermarriages common among Egyptian royalty.

Through meticulous analysis, scientists reconstruct Tutankhamun's physical attributes, revealing a frail ruler beset by ailments like buck teeth, a club foot, and girlish hips. Far from the image of a vigorous chariot racer, Tutankhamun relied on walking sticks to navigate his realm.

The unveiling of the true cause behind the 'Pharaoh's curse' not only reshapes our understanding of ancient beliefs but also offers a poignant glimpse into the life and death of one of history's most iconic figures.

From the Earth, Not the Sky: Debunking Extraterrestrial Theories of the Nazca Lines

Myth Versus Reality: How the Nazca Lines Were Truly Meant to Be Seen

The arid plains of Peru’s Nazca Desert hold one of the world’s most enigmatic archaeological enigmas: the Nazca Lines. These colossal geoglyphs, created by the Nazca culture between 500 BCE and 500 CE, consist of hundreds of figures ranging from geometric patterns to stylized images of animals, plants, and mythical shapes. Stretching across nearly 450 square kilometers, these lines have puzzled historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts for decades.

Origins and Discovery

The Nazca Lines were not widely known until the 20th century, when airplanes flying overhead revealed the vast and intricate designs etched into the landscape. This discovery propelled a myriad of theories about their purpose and creation, transforming them into a focal point for both scientific research and popular speculation.

Visibility and Purpose

One of the most striking aspects of the Nazca Lines is that they can be seen from the surrounding hilltops and even more distinctly from the Andes mountains nearby. This visibility refutes the more fantastical theories that claim only gods or extraterrestrial beings should be able to see the lines from above. Instead, it suggests that the Nazca people designed these geoglyphs with both an understanding and an appreciation of their natural landscape.

Archaeologists have proposed that the lines served a multifaceted set of purposes, blending the practical with the spiritual. Some suggest that the lines functioned as astronomical markers, aligning with key celestial events, which were critical in an agricultural society dependent on the seasonal cycles. Others believe the lines were part of ritualistic processes, perhaps used as sacred paths during religious ceremonies dedicated to deities who controlled fertility and water, crucial elements in the harsh desert environment.

Construction Techniques

The method of their creation is equally impressive. The geoglyphs were formed by removing the reddish pebbles that cover the terrain to reveal the lighter earth beneath. This technique not only required laborious effort but also an intricate knowledge of geometric design and spatial organization. The precision of the lines, some stretching up to several kilometers in length, showcases Nazca's sophisticated understanding of mathematics and surveying.

Debunking the Mythical

The visibility of the geoglyphs from nearby highlands also debunks more speculative theories, such as those suggesting the Nazca used hot air balloons to survey their constructions. Mainstream archaeology considers these theories a distraction from the true ingenuity of the Nazca culture. The lines were likely not meant for the gods in the sky but for rituals observed by participants walking along the paths, engaging directly with the figures etched into the earth.

Legacy and Preservation

Today, the Nazca Lines are a UNESCO World Heritage Site, protected and studied as precious relics of human creativity and ingenuity. The ongoing challenge is to preserve these vulnerable designs from threats such as climate change, erosion, and human activities. The lines have survived centuries, and with careful preservation, they can continue to fascinate and inspire generations to come.

The Nazca Lines remind us of the human capacity to reshape our environment into profound cultural expressions. These geoglyphs are not messages to be read from the heavens but monumental artworks that speak of the human spirit, ingenuity, and the eternal desire to commune with the cosmos.

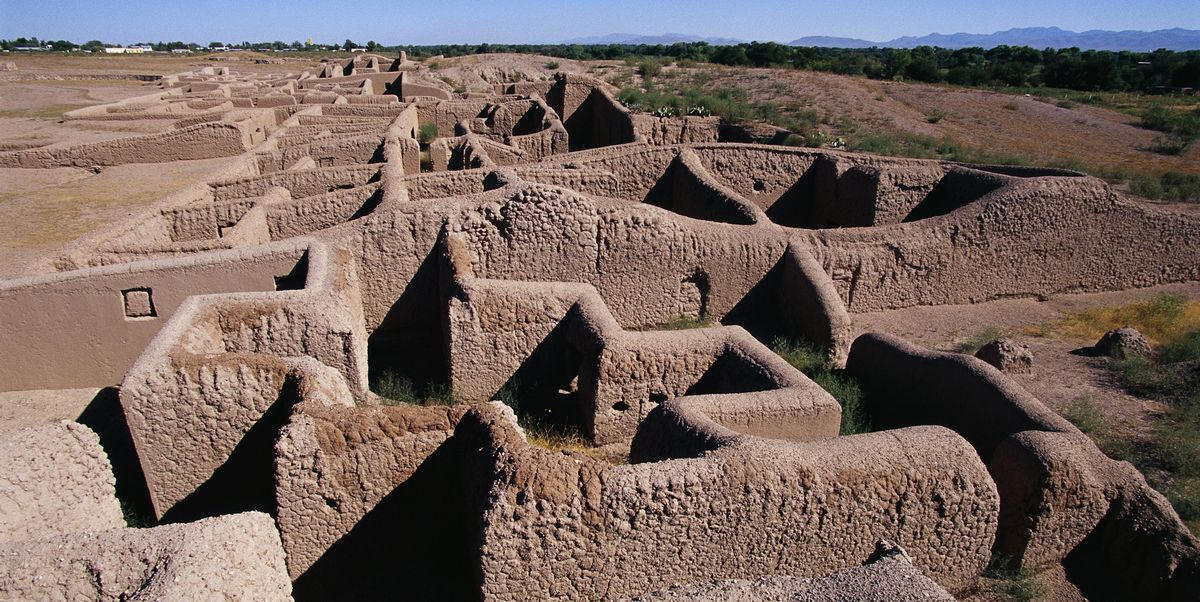

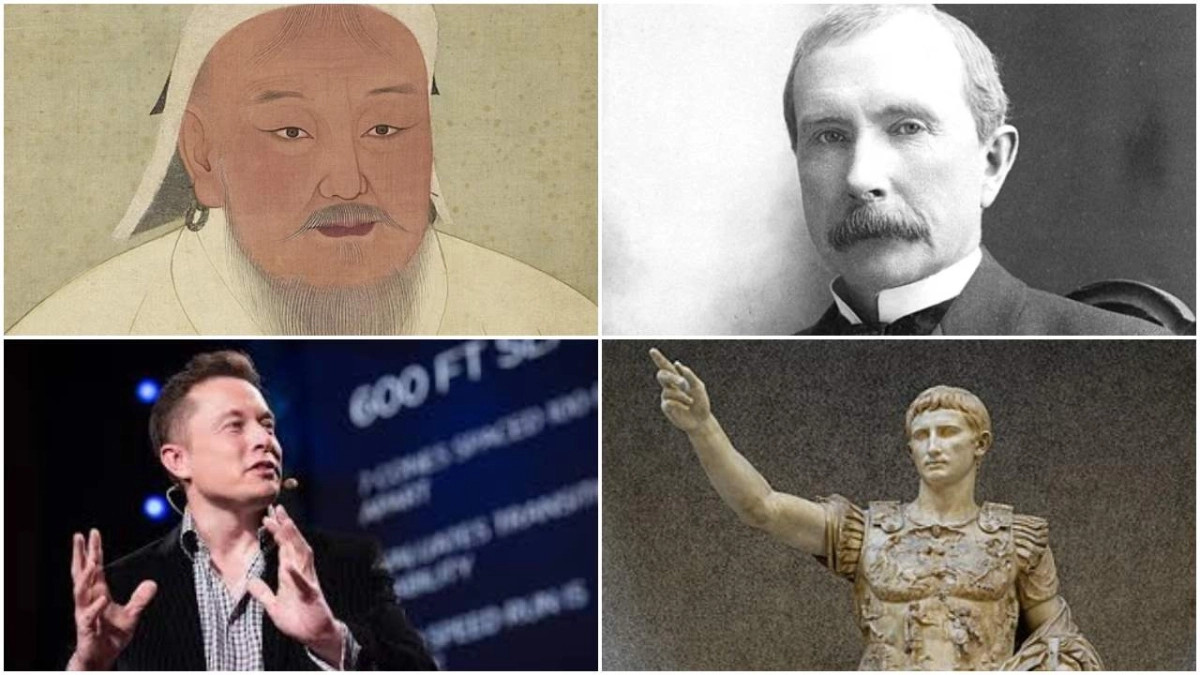

Why Empires and Civilizations Collapse: A Look at the Factors Leading to Societal Collapse

Throughout history, mighty empires have risen and fallen, leaving behind magnificent ruins and cautionary tales. Understanding the reasons behind these collapses can help us identify potential weaknesses in our own societies and strive for a more stable future. This article explores some of the key factors that have contributed to the downfall of past civilizations.

The Sack of Rome in 410 by the Barbarians by Joseph-Noël Sylvestre, 1890

External Threats:

War and Invasion: Empires engaged in constant warfare can become stretched thin, leaving themselves vulnerable to attack by stronger forces. The fall of the Western Roman Empire is a prime example, where barbarian invasions chipped away at the empire's borders until it could no longer defend itself .

Mass Migration: Large influxes of refugees fleeing war, famine, or persecution can strain a society's resources and lead to social unrest. The collapse of the Han Dynasty in China is partly attributed to mass migrations from nomadic groups on the northern borders.

Environmental Challenges:

Climate Change: Gradual shifts in climate patterns can disrupt agricultural production and lead to food shortages. The demise of the Mayan civilization is believed to be linked to a prolonged drought.

Resource Depletion: Societies heavily reliant on specific resources, like timber or fertile land, can face collapse if those resources become depleted. Easter Island's deforestation is a stark example of how environmental mismanagement can lead to societal decline.

Economic Troubles:

Inequality and Overspending: When wealth concentrates in the hands of a few, the majority of the population can suffer. This economic disparity can breed resentment and social unrest. The decline of the Roman Republic is partly attributed to the widening gap between rich and poor.

Unsustainable Practices: Empires that prioritize short-term gain over long-term sustainability can sow the seeds of their own destruction. Deforestation, soil depletion, and poor water management can all contribute to economic decline.

Internal Decay:

Corruption and Ineffective Leadership: Leaders who prioritize self-interest over the well-being of their citizens can erode public trust and weaken the fabric of society. The later Roman emperors are often cited as examples of corrupt leadership that contributed to the empire's downfall.

Social Cohesion: A strong sense of shared identity and purpose is essential for a society to thrive. If social divisions deepen and trust breaks down, a society can become vulnerable to internal conflict.

Disease:

Epidemics: The spread of infectious diseases can devastate a population, leading to labor shortages, famine, and social disorder. The Black Death, which swept through Europe in the 14th century, is a chilling example of how disease can contribute to societal collapse.

A Complex Interplay:

It's crucial to remember that these factors rarely act in isolation. More often than not, a combination of these events will push a society to the brink of collapse. For instance, an environmental disaster might weaken a society, making it more susceptible to invasion or internal rebellion.

Learning from the Past:

By studying the collapse of past civilizations, we can gain valuable insights into the potential weaknesses of our own societies. This knowledge can help us develop more sustainable practices, strengthen social cohesion, and prepare for potential threats.

Sources:

https://www.palladiummag.com/2024/03/08/why-civilizations-collapse/

https://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/green-science/civilizations-collapse.htm

Enigmatic Roman dodecahedron discovered in Lincolnshire to go on display in county for the first time

Discovering a piece of ancient history is always a thrilling adventure, and the unearthing of the Roman dodecahedron in Norton Disney, near Lincoln, adds a fascinating chapter to the annals of archaeological discovery. This remarkable find, crafted from copper alloy and believed to hail from the third or fourth century, has captured the attention of historians and enthusiasts alike. Found intact and astonishingly well-preserved during a summer excavation in 2023, this hollow, 12-sided object stands as one of the most significant archaeological discoveries in recent memory.

Measuring approximately 8cm in height and weighing 245g, the Norton Disney dodecahedron stands as one of the largest examples of its kind. Its discovery marks not only the first occurrence of such an artifact in the Midlands but also joins a select group of only 33 dodecahedrons found across Britain. Unlike many of its counterparts, which have been unearthed in fragmented or damaged states, the Norton Disney specimen remains complete, offering researchers a pristine glimpse into the past.

Despite its prominence, the true purpose of these enigmatic objects remains shrouded in mystery. Absent from Roman texts and depictions, the dodecahedron's significance is a subject of conjecture, with scholars speculating that it may have held ritualistic or religious importance. Its presence defies practical explanation, leaving ample room for imagination and speculation regarding its original function.

Now, after centuries of obscurity, the Norton Disney dodecahedron is set to make its debut in its home county. As part of the Lincoln Festival of History, beginning on May 4th and running until early September 2024, this extraordinary artifact will be on public display at the Lincoln Museum. Coinciding with the festival's inaugural celebration, visitors will have the opportunity to witness this ancient marvel firsthand, mere miles from where it was unearthed.

The Festival of History promises a journey through time, offering attendees a chance to engage with Lincoln's rich heritage. In addition to the dodecahedron exhibition, visitors can immerse themselves in the world of the ancient Romans, as the museum hosts a legion reenactment in its atrium. Moreover, the museum's archaeology gallery showcases a plethora of Roman treasures unearthed throughout the city and county, providing further insight into the region's past.

For those eager to delve deeper into Lincoln's history, guided tours of Posterngate offer a glimpse beneath the city streets, where remnants of a hidden Roman gateway await discovery. These tours, a highlight of the festival, offer a unique perspective on Lincoln's ancient roots and are sure to captivate history enthusiasts of all ages.

Andrea Martin, exhibitions and interpretations manager at Lincoln Museum, expresses delight at the prospect of showcasing the Norton Disney dodecahedron to the public for the first time in Lincolnshire. She emphasizes the significance of the artifact's debut, particularly amidst the backdrop of the Festival of History, which promises to be a delight for history enthusiasts and visitors alike.

Richard Parker, secretary of the Norton Disney History and Archaeology Group, reflects on the enduring mystery surrounding the dodecahedron and the global interest it has generated. Despite extensive research, the object's purpose remains elusive, sparking a flurry of speculation and inquiry. Parker hints at future excavations in the area, hopeful that further discoveries may shed light on the artifact's origins and significance.

The Norton Disney dodecahedron's journey to prominence extends beyond local acclaim, as it garnered international attention, including a feature on BBC's "Digging for Britain." Now, it invites visitors to embark on their own journey through time at Lincoln Museum, where admission is free, offering a glimpse into a bygone era rich with intrigue and mystery.

But the Festival of History offers more than just a glimpse into the past. From the Castle Zone at Lincoln Castle to the Victorian adventure awaiting at the Museum of Lincolnshire Life, the festival promises a diverse array of experiences sure to delight visitors of all interests. For a comprehensive guide to the festival's events, visitors are encouraged to explore the Visit Lincoln website and embark on a journey through the annals of history.

Illustration by Dimosthenis Vasiloudis

The Labrys: Exploring the Evolution of the Sacred Double Axe from Neolithic Anatolia to the Minoan Labyrinth

The Labrys as a Cultural Keystone from Çatal Höyük to Knossos

The odyssey of the labrys, a symbol par excellence of divine authority and ritual, commences long before its renowned association with the Minoan civilization. Originating within the prehistoric tapestry of Anatolia, specifically at the site of Çatalhöyük, the labrys' presence can be traced back to a society flourishing from 7500 to 5700 BCE. Already from that time, the double axe emerges not merely as a tool but as a ceremonial artifact, integral to the worship practices of early agrarian communities.

As the embodiment of power and religious life, the labrys traversed maritime routes from the Anatolian and Greek mainlands to Minoan Crete, where it became a central motif in the island's intricate palatial complexes and religious iconography, reflecting a narrative of cultural transmission and adaptation that spanned across centuries.

From Neolithic Anatolia to Minoan Crete: The Journey of the Labrys

The ancient Greeks referred to the double axe as "labrys," a term steeped in mystery and hailing from the depths of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods of Anatolia. This word had already found relevance during the Minoan era, hinting at a connection with the term "labyrinth." Plutarch notes that 'labrys' is the Lydian term for 'axe,' stating: "The Lydians call the double-edged axe 'labrys.'"

Originating in the East, the double axe's earliest representations are traced back to Çatalhöyük, an early Neolithic proto-city in Anatolia. Its depiction was not only artistic but symbolic, reflecting the complex, maze-like layout of the settlement. The oldest artifact of a double axe unearthed to date was at Gürcü Tepe, situated east of Çatalhöyük, within a similar cultural sphere. Gürcü Tepe's rural character suggests that the double axe served an apotropaic role, warding off evil.

At Çatalhöyük, one encounters the double axe intermingled with bull iconography within the community's intricate art. Bulls are rendered with detailed anatomical precision, symbolizing virility and fecundity within this early agrarian society. The double axe, appearing both in art and as tangible relics, likely bore a sacred import, potentially linked to male divinities or sacrificial rituals. These symbols reflect the spiritual practices and complex social structures of one of humanity's initial urban centers.

The emblematic significance of the double axe on Crete is believed to stem from the Neolithic settlers' religious beliefs, which were characterized by reverence for an Earth Mother Goddess, indicative of the island's enduring spiritual traditions. In Minoan Crete, the labrys fulfilled both ritual and votive roles. It was the primary instrument in the ceremonial sacrifice of sacred bulls and was also offered in burial rites, caves, and peak sanctuaries. Seals and the Archanes Script provide evidence of the double axe's significance, which was so ingrained in Minoan culture that it predates the Prepalatial Period. The Minoan religion was anchored in the veneration of the Mother Goddess, a primordial figure of fertility, reproduction, and the cyclical rebirth of nature.

The double axe holds a venerable place in the mythology of ancient Near Eastern cultures, symbolizing the might of deities like the Hurrian sky and storm god, Teshub. In Hittite and Luwian traditions, this god was known as Tarhun, often depicted wielding a double axe alongside a triple thunderbolt—a clear emblem of his dominion over storms. This formidable storm god is also depicted on a relief brandishing a double axe, a symbol of his power, as he stands over a bull. In parallel, the Greek god Zeus is traditionally depicted hurling thunderbolts, employing the labrys, or pelekys, as his instrument to command the storm. Intriguingly, the modern Greek term for lightning, "astropeleki" (ἀστροπελέκι), translates to "star-axe," perpetuating the ancient association of the axe with celestial power.

The worship of the double axe on the Greek island of Tenedos and other locations in southwestern Asia Minor is evidence that this reverence persisted into classical antiquity. The labrys also found its place in the worship practices associated with the Anatolian thunder god, further evidenced in the Hellenistic period with the cult of Zeus Labrayndeus, where the labrys continued to be a potent symbol of divine storm-making power. This continuity of the double axe's symbolism across different cultures and eras reflects its enduring significance in the religious and mythological landscape of the Mediterranean and Near East.

The depiction of bulls and double axes across various ancient cultures—from the bull frescoes of Çatalhöyük and Minoan bull-leaping iconography to the imagery of the Hittite and Luwian god Tarhun wielding a double axe over a bull—suggests a hypothetical cultural linkage. These symbols, recurring throughout ancient Anatolia and Crete, may signify a shared mythological language where the bull symbolizes strength and fertility, and the double axe represents divine authority, reflecting an enduring tradition of reverence and ritual that transcends regional and temporal boundaries.

A Roman bronze ensign of Jupiter Dolichenus. One can make out other deities including Hercules, Victoria, Luna and perhaps in the lower right hand corner is Mars. This amazing piece is on display in the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest, Hungary.

The Linguistic Enigma: Labrys, labraunda and the Greek Labyrinthos

The path of the labrys intertwines with the evolution of language, presenting a fascinating enigma that captivates linguists and historians alike. The term 'labrys' finds its echoes in the pre-Greek word 'labyrinthos,' an association derived from the interpretation of ancient texts, most notably a Linear B tablet that references the 'Mistress of the Labyrinth.' This coupling of the labrys with the intricate and complex structure of the labyrinth carries profound implications, suggesting a sacred dimension wherein the axe is not only a symbol of divine power but also an architectural metaphor. The linguistic fluidity of ancient Greek, where phonemes like 'd' and 'l' could interchange (Dabraundos, dabrys), adds layers of complexity to this enigma, inviting scholars to delve deeper into the maze of historical language development.

The word "labrys," which the Lydians or Carians used to refer to a double-edged axe, also serves as the basis for the name of the renowned labyrinth of Knossos, indicating an intriguing cultural connection between the civilizations of Western Anatolia and Minoan Crete. The labyrinth is often interpreted as the "place of the axe," a phrase that resonates with the central role of the labrys within both Minoan and Carian sacred spaces. The significance of the labrys is further highlighted by its enduring presence in Carian religious sites, such as Labraunda, where it was revered as a holy artifact.

The term "labrys," first noted in English in 1901 according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is intimately linked to the ancient Carian sanctuary of Labranda. This connection highlights the significance of the labrys as a sacred object. The sanctuary's name, Labranda, is directly derived from this term, suggesting that it was a place where the labrys held religious importance. This interpretation casts the sanctuary not just as a geographical location but as a spiritual center dedicated to the veneration of the labrys, reinforcing its status as a potent symbol of divine or royal power in ancient Anatolia.

It is amazing how symbols and gods from different cultures came together at Labraunda. In the mountainous terrains of Caria, five kilometers west of Ortaköy, Mugla Province of modern Turkey, the labrys finds a sacred echo at this site, which is steeped in divine resonance. Here, the double-headed axe stands beside Zeus Labrandeus, a syncretic deity embodying the storm's might, a testament to the symbol's enduring sacral status. Revered along with the Olympian gods, it shows that religious and artistic traditions from Anatolia and Greece were constantly exchanging ideas and images. The presence of the labrys in this sacred milieu underscores its dynamic role as a venerated object of worship, a focal point of divine communion, and an emblem of spiritual continuity in the ancient Mediterranean tapestry.

A legendary account tells of a golden double-headed axe that held a place of honor in the Lydian capital of Sardes. King Gyges of Lydia gave the Carians this sacred labrys as a thank-you gift for their military assistance. The complexity of such an exchange underlines the ceremonial importance of the labrys, a symbol not easily relinquished or transferred between peoples. Once in the possession of the Carians, it was enshrined in the Temple of Zeus at Labranda, emphasizing its continued ritual significance.

In the city of Halicarnassus, the labrys became a numismatic emblem, frequently depicted on coinage, signaling its broader symbolic currency in Carian society. The museum in Bodrum houses coins that not only depict the familiar head of Apollo but also the esteemed figure of Zeus Labraundeus, distinguishable by the double-bladed Carian axe. This consistent iconography across various mediums and contexts, from coins to sanctuaries, denotes the profound link between the labrys and the divine, thereby weaving a thread of shared cultural and religious (and now also genetic) identity between the civilizations of the Greek mainland, Minoan Crete, and Western Anatolia.

Scholarly Discourse and Alternative Interpretations

Amidst the converging lines of historical evidence and myth, the origin and meaning of 'labyrinthos' spark ongoing scholarly debate. While the association with the labrys suggests a lineage tied to Minoan ritual spaces, other scholars cast a wider net, proposing alternatives such as a linguistic link to Greek 'laura' or even a borrowing from Carian terms. These discourses reflect the complexities and challenges inherent in unraveling the etymological threads of ancient words, with each interpretation offering a unique perspective on the intersections of language, archaeological evidence, culture, and religion. As the labrys continues to serve as a nexus for these discussions, its journey from a utilitarian axe to a profound cultural symbol encapsulates the rich spectrum of ancient Mediterranean spirituality and the scholarly pursuit to understand it.

When Was the Number 0 First Used?

Zero: A Journey from Emptiness to Infinity

The number zero, though seemingly simple, boasts a rich history intertwined with philosophical and mathematical advancements. Its journey from representing nothingness to becoming the foundation of our number system is a fascinating tale of human ingenuity.

Early Traces of Nothingness

The quest for zero began in the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia. Around 4,000 years ago, Sumerian scribes used empty spaces in their clay tablets to denote the absence of a value in their counting system. This wasn't a true zero, but it marked the first attempt to represent nothingness. Similarly, Egyptians and Romans lacked a symbol for zero, hindering the development of complex mathematical concepts.

The Birth of Shunya in India

The concept of zero truly blossomed in ancient India. By the 5th century B.C., Indian mathematicians were using the Sanskrit word "shunya," meaning void or emptiness, to represent zero. This philosophical concept likely stemmed from Buddhist ideas of emptiness or "shunyata." Around the 9th century A.D., the Gwalior inscription emerged, showcasing the first documented use of a zero symbol in the decimal system, a small circle.

From India to the World

The brilliance of zero transcended borders. Arab mathematicians, like Al-Khwarizmi in the 8th century A.D., embraced the Indian numeral system, including zero. Al-Khwarizmi's work on algebra, which literally translates to "the balancing" (referring to equations), heavily relied on the concept of zero. Through Arabic translations, zero journeyed westward, reaching Europe by the 12th century.

Zero's Impact: A Mathematical Revolution

The arrival of zero in Europe sparked a mathematical revolution. The cumbersome Roman numeral system struggled to represent large numbers efficiently. Zero, along with the positional number system (where a digit's value depends on its place), offered a superior method for calculations. This paved the way for advancements in science, engineering, and navigation during the Renaissance and beyond.

Beyond Mathematics: A Philosophical Symbol

Zero's influence extended beyond mathematics. In philosophy, it challenged the notion of absolute nothingness, representing instead a potential or starting point. In physics, it signified the absence of a specific quantity, allowing for the development of concepts like absolute temperature.

Zero: A Legacy of Innovation

Today, zero stands as a cornerstone of mathematics and a testament to human curiosity and innovation. Its journey from representing emptiness to enabling us to explore infinity highlights the power of intellectual exchange and the transformative potential of a simple concept.

Alexander The Great Cities: 13 Settlements Established by Alexander the Great

This article provides an in-depth look at the settlements founded or re-established under the directive of Alexander the Great himself. These settlements were established during his reign and before his death in 323 BC. Excluded from this list are any posthumous foundations or refoundations, as well as settlements that merely claimed a connection to the Macedonian king.

Settlements

Alexandria near Egypt

Alternative Name(s): Alexandria, Egypt

Year Founded: 331 BC

Location: Alexandria, Egypt

Description: This was one of the earliest major foundations of Alexander's reign. Situated in the western Nile Delta between Lake Mareotis and the Mediterranean Sea, its founding circumstances are subject to debate. The city's significance grew over time, becoming one of the world's most important cities by 1 AD.

Historical Authenticity: Accepted

Alexandria Ariana

Year Founded: 330 BC

Location: Near modern Herat, Afghanistan

Description: Although not mentioned by Greek historians like Arrian or Diodorus Siculus, the existence of Alexandria Ariana is supported by geographers and Islamic chroniclers. Its exact location near present-day Herat remains unknown, but evidence suggests its establishment in a fertile oasis on major trade routes.

Historical Authenticity: Accepted

Alexandria Arachosia

Year Founded: 330 BC

Location: Kandahar, Afghanistan

Description: References to a city named Alexandria in Arachosia exist in various sources. While its identification with Old Kandahar is disputed, epigraphic evidence and early Islamic references support its existence. The city likely played a significant role in the region's trade and culture.

Historical Authenticity: Accepted

Alexandria Eschate

Year Founded: 329 BC

Location: Likely near Khujand, Tajikistan

Description: Founded to defend against Scythian tribesmen, Alexandria Eschate was settled with Greek mercenaries, local tribesmen, and injured Macedonian veterans. Its location, likely near Khujand, held strategic importance controlling trade routes and access to the Ferghana Valley.

Historical Authenticity: Accepted

Alexandria in the Caucasus / Alexandria in Parapamisdai

Year Founded: 329 BC

Location: Near the Hindu Kush

Description: This settlement, although not identified by its modern name, is accepted by major historians. Established south of the Hindu Kush, it served as a key outpost, resettling native populations and retired soldiers.

Historical Authenticity: Accepted

Boukephala and Nikaia

Year Founded: 326 BC

Location: Opposite sides of the Hydaspes river, Pakistan

Description: Founded after Alexander's victory over Porus, these cities faced each other across the Hydaspes River. While their exact locations remain uncertain, they symbolized Alexander's conquests and honored his favorite stallion, Bucephalus.

Historical Authenticity: Accepted

Charax Spasinu / Alexandria in Susiana

Year Founded: 324 BC

Location: Likely Naysan, Iraq

Description: Initially known as Charax Spasinu, this settlement was likely established as a trading hub at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Its later renaming and rebuilding indicate its historical significance in the region.

Historical Authenticity: Accepted

Alexandria Troas

Year Founded: 334 BC

Location: Troad, modern Çanakkale, Turkey

Description: While most attribute its foundation to Antigonus I, some theories suggest Alexander's involvement. The city's historical attribution remains disputed among historians.

Historical Authenticity: Disputed

Samareia

Year Founded: 332–331 BC

Location: Modern Sebastia, State of Palestine

Description: Allegedly settled after a rebellion, Samareia's origins are uncertain. Speculation ranges from Alexander's era to post-Alexander settlements.

Historical Authenticity: Disputed

Gerasa / Antioch on the Chrysorhoas

Year Founded: 331 BC

Location: Jerash, Jordan

Description: While a late tradition connects it to Alexander, evidence suggests a possible establishment by his generals. The exact connection remains speculative.

Historical Authenticity: Disputed

Alexandria in Margiana

Year Founded: 328 BC

Location: Gyaur-Kala, Turkmenistan

Description: Despite early attestations, debates continue over whether Alexander or the Seleucids founded this settlement. Its origins remain contested.

Historical Authenticity: Disputed

Alexandria Rhambakia

Year Founded: 325 BC

Location: Near the mouth of the Indus River in Balochistan, Pakistan

Description: Its founding under Alexander's orders is speculated but not conclusively proven due to geographical changes over time.

Historical Authenticity: Uncertain

Alexandria near Babylon

Year Founded: Unknown

Location: Unknown

Description: Identification of this settlement faces challenges, with theories suggesting its existence under different names or under subsequent rulers.

Historical Authenticity: Uncertain

This comprehensive overview sheds light on the diverse array of settlements established or attributed to Alexander the Great, each contributing to the rich tapestry of ancient history.

Sources

Cohen, Getzel (1995). The Hellenistic settlements in Europe, the islands, and Asia Minor. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cohen, Getzel (2013). The Hellenistic Settlements in the East from Armenia and Mesopotamia to Bactria and India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fraser, Peter M. (1996). Cities of Alexander the Great. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

100 Ancient Japanese Names (Males and Females)

Embark on a journey through time and tradition with 'Echoes of Eternity,' a captivating exploration of 100 ancient Japanese names. Each name carries with it a rich tapestry of history, culture, and significance, resonating with the echoes of generations past. From legendary samurai to revered deities, these names offer a window into the soul of Japan's storied past. Delve into the meanings behind each name, uncovering tales of valor, wisdom, and timeless beauty. Whether you seek inspiration for a character, story, or simply wish to immerse yourself in the heritage of Japan, 'Echoes of Eternity' promises an enchanting odyssey through the ancient realms of Japanese nomenclature.

Male Names:

Hachiman - Hachiman, the "God of War" in Japanese mythology, is revered for his strength, protection, and martial prowess. Often depicted as a fierce warrior, Hachiman is also associated with divine justice and guidance in battle.

Yoshitsune - Yoshitsune, a name synonymous with heroism and adventure, belongs to Minamoto no Yoshitsune, one of Japan's most celebrated samurai warriors. The name itself means "Good Fortune" and "Sound," reflecting his enduring legacy.

Takeshi - Takeshi, a name imbued with strength and valor, is often associated with warriors and heroes. Derived from the Japanese word for "Fierce" or "Valiant," Takeshi evokes images of courage in the face of adversity.

Hideyoshi - Hideyoshi, a name steeped in the history of feudal Japan, belongs to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a legendary daimyo and unifier of Japan in the late 16th century. The name Hideyoshi itself means "Excellence" and "Good Luck," reflecting his remarkable achievements.

Nobunaga - Nobunaga, a name synonymous with ambition and power, belongs to Oda Nobunaga, one of Japan's most iconic feudal lords. The name Nobunaga means "Trust" and "Eternal," reflecting his enduring influence on Japanese history.

Masamune - Masamune, a name steeped in tradition and honor, is synonymous with legendary swordsmiths and warriors. The name itself means "Righteous" and "True," reflecting the noble ideals upheld by those who wielded Masamune swords.

Kiyomizu - The name Kiyomizu holds a poetic charm, evoking images of purity and clarity. It is derived from the famous Kiyomizu-dera temple in Kyoto, known for its stunning architecture and breathtaking views. The word "Kiyomizu" translates to "Pure Water," symbolizing both physical and spiritual cleansing.

Akio - Akio, a name signifying "Bright Man," carries connotations of intelligence and wisdom. It symbolizes a person who illuminates the path with their knowledge and insight, guiding others toward understanding and enlightenment.

Ryota - Ryota, a name that translates to "Clear" or "Refreshing," reflects purity and transparency. It suggests a person with a straightforward and honest nature, unclouded by deception or ambiguity.

Jiro - Jiro, a name with a long history in Japan, carries connotations of strength and reliability. Derived from the characters for "Second" and "Son," Jiro signifies a familial connection and responsibility. Throughout Japanese literature and folklore, individuals named Jiro are often portrayed as loyal and dependable companions.

Daichi - Daichi, a name synonymous with strength and stability, holds deep roots in Japanese tradition. Combining the characters for "Great" and "Earth," Daichi represents the boundless power and resilience of the natural world. It is a name often chosen to inspire courage and fortitude in the face of life's challenges.

Haruki - Haruki, a name with deep literary roots, is associated with renowned Japanese authors like Haruki Murakami. The name itself means "Shining Brightly," reflecting a radiant and luminous presence. Haruki embodies creativity, enlightenment, and the pursuit of artistic expression.

Kenji - Kenji, meaning "Intelligent Second Son," represents a person of great intellect and potential. It signifies the wisdom and capability of a second-born child, often associated with resourcefulness and adaptability.

Taro - Taro, derived from the Japanese word for "First Son," carries a sense of primacy and leadership within the family. It symbolizes responsibility and authority, often associated with the eldest son in Japanese households.

Rokuro - Rokuro, a name that translates to "Sixth Son," signifies familial lineage and order. It reflects the hierarchical structure of traditional Japanese families, where birth order plays a significant role in social dynamics.

Akira - Akira, meaning "Bright" or "Clear," symbolizes clarity, enlightenment, and intellectual brilliance. It represents a person of keen intellect and insight, who illuminates the path with their wisdom and understanding.

Isamu - Isamu, a name that means "Courage" and "Bravery," signifies strength, valor, and resilience in the face of adversity. It represents the indomitable spirit and unwavering determination that empowers individuals to overcome challenges and obstacles.

Kaito - Kaito, a name that translates to "Ocean Flying," evokes a sense of freedom, adventure, and exploration. It represents a person who yearns to spread their wings and soar to new heights, embracing life's journey with boundless enthusiasm.

Katsuro - Katsuro, meaning "Victorious Son," symbolizes triumph, success, and achievement. It represents a person who overcomes obstacles and emerges victorious in the face of adversity, embodying the spirit of resilience and determination.

Noboru - Noboru, meaning "Ascend" or "Rise," signifies upward movement, progress, and growth. It represents the journey of self-improvement and personal development, as well as the pursuit of higher aspirations and goals.

Ren - Ren, a name that signifies "Lotus" or "Love," embodies purity, enlightenment, and spiritual awakening. It represents the journey of growth and transformation, rising above adversity to achieve inner peace and harmony.

Koichi - Koichi, a name that translates to "Bright One," symbolizes illumination, enlightenment, and intellectual brilliance. It represents a person who shines with inner wisdom and clarity of thought.

Yua - Yua, meaning "Binding Love," symbolizes the unbreakable bond of affection and connection between individuals. It represents the deep-seated emotions and shared experiences that unite people in love and friendship.

Daisuke - Daisuke, a name that means "Great Help" or "Great Opportunity," signifies support, assistance, and benevolence. It represents a person who extends a helping hand to others in times of need, offering guidance and encouragement along life's journey.

Mitsuru - Mitsuru, a name that signifies "Fulfillment" or "Satisfactory," embodies completeness, contentment, and fulfillment. It represents the sense of satisfaction and fulfillment that comes from achieving one's goals and aspirations.

Tadao - Tadao, meaning "Fulfillment" or "Satisfying," signifies completeness, contentment, and fulfillment. It represents the sense of satisfaction and fulfillment that comes from living a meaningful and purposeful life.

Satoshi - Satoshi, a name that signifies "Clear Thinking" or "Quick Witted," embodies intelligence, wisdom, and sharp intellect. It represents the ability to think critically and solve problems with clarity and precision.

Kazumi - Kazumi, meaning "Harmonious Beauty," signifies balance, harmony, and elegance. It represents the aesthetic beauty and tranquility found in the harmonious interplay of elements.

Naoki - Naoki, a name that translates to "Honest Tree," embodies strength, stability, and reliability. It represents the steadfastness and resilience of individuals who remain true to their values and principles.

Toshiko - Toshiko, a name that signifies "Clever" or "Smart," embodies intelligence, wit, and sharp intellect. It represents the ability to think critically and solve problems with ingenuity and resourcefulness.

Mitsuko - Mitsuko, meaning "Child of Light," embodies brightness, illumination, and enlightenment. It represents the radiant energy and positive outlook that brighten the lives of those around them.

Kenzo - Kenzo, meaning "Strong and Healthy," symbolizes robustness, vitality, and well-being. It represents the resilience and endurance that enable individuals to thrive and flourish in all aspects of life.

Ryoko - Ryoko, a name that means "Refreshing Child," evokes feelings of vitality, energy, and rejuvenation. It represents the vibrant spirit and zest for life that define youthfulness and vigor.

Yukio - Yukio, meaning "Snow Boy," evokes images of purity, innocence, and tranquility. It represents the serenity and beauty of a snowy landscape, as well as the quiet strength that lies within.

Yukari - Yukari, a name that signifies "Beautiful Pearls," embodies elegance, refinement, and sophistication. It represents the exquisite beauty and timeless allure of pearls, as well as the grace and poise of individuals who possess inner beauty.

Female Names:

Tomoe - Tomoe, a name associated with bravery and skill in archery, belongs to Tomoe Gozen, a legendary female samurai warrior. The name itself means "Wisdom" and "Blessing," reflecting her courage and martial prowess.

Sachiko - Sachiko, a name that means "Child of Bliss," embodies joy, happiness, and contentment. It represents the boundless joy and delight that comes from experiencing life's blessings.

Hanako - Hanako, a name often associated with grace and beauty, signifies elegance, refinement, and inner strength. It represents the timeless allure and charm of individuals who possess both physical beauty and inner grace.

Emiko - Emiko, a name brimming with warmth and positivity, is a popular choice for girls in Japan. Combining the characters for "Smile" and "Child," Emiko signifies a cheerful and optimistic disposition. With its melodic sound and uplifting meaning, Emiko brings joy to those who bear it and those around them.

Ayame - Ayame, a name as beautiful as the flower it represents, is derived from the Japanese word for "Iris." In Japanese culture, the iris (ayame) holds symbolic significance, representing courage, protection, and inner strength. Ayame is a popular choice for girls, embodying qualities of resilience and grace.

Yuriko - Yuriko, meaning "Lily Child," exudes purity, innocence, and grace. It symbolizes the delicate beauty of the lily flower and the untarnished purity of youth.

Yoko - Yoko, meaning "Sunlight Child," radiates warmth, positivity, and optimism. It symbolizes the light that shines from within, illuminating the lives of those around them with its gentle glow.

Miki - Miki, a name that signifies "Beautiful Princess," embodies grace, elegance, and regal charm. It evokes the image of a noble and dignified individual who commands respect and admiration.

Asuka - Asuka, a name meaning "Tomorrow's Fragrance," suggests anticipation and promise for the future. It embodies optimism and the hope for better days ahead, akin to the sweet aroma that lingers in the air with the dawn of a new day.

Natsumi - Natsumi, a name meaning "Summer Beauty," embodies the allure and vitality of the summer season. It evokes images of sun-kissed days, lush landscapes, and carefree moments of joy.

Ayaka - Ayaka, meaning "Colorful" or "Flower Petal," embodies vibrancy, beauty, and elegance. It represents a person who brings joy and brightness to the lives of those around them, like a colorful flower in full bloom.

Yuna - Yuna, meaning "Gentle" or "Tender," evokes feelings of kindness, compassion, and empathy. It represents the nurturing and caring nature of individuals who extend warmth and understanding to others.

Mariko - Mariko, a name that translates to "Child of True Beauty," embodies grace, elegance, and inner beauty. It represents the timeless allure and charm of individuals who radiate beauty from within.

Mina - Mina, a name that signifies "South" or "Vegetables," embodies growth, fertility, and nourishment. It represents the abundance of nature and the cycle of life, as well as the nurturing care and sustenance provided by the earth.

Misaki - Misaki, meaning "Beautiful Blossom," embodies the delicate beauty and ephemeral nature of flowers. It represents the fleeting moments of beauty and joy that enrich one's life, as well as the cycle of growth and renewal.

Reina - Reina, meaning "Queen" or "Elegant," embodies grace, dignity, and sophistication. It represents the regal bearing and noble character of individuals who carry themselves with poise and refinement.

Suzu - Suzu, a name that translates to "Bell," evokes the gentle tinkling sound of a bell, bringing a sense of peace, tranquility, and mindfulness. It represents the awakening of inner awareness and the call to mindfulness in daily life.

Hana - Hana, meaning "Flower," symbolizes beauty, grace, and the ephemeral nature of life. It represents the delicate yet resilient spirit of individuals who bloom with vitality and grace, even in the face of adversity.

Haruka - Haruka, a name that means "Distant" or "Far Away," embodies a sense of longing, exploration, and discovery. It represents the journey of self-discovery and the pursuit of one's dreams and aspirations, no matter how distant they may seem.

Aya - Aya, a name that signifies "Color" or "Design," represents creativity, expression, and individuality. It embodies the unique essence of each person's identity and the beauty that arises from embracing one's true self.

Haruko - Haruko, meaning "Spring Child," evokes feelings of renewal, rejuvenation, and vitality. It represents the fresh start and new beginnings that come with the arrival of spring.

Airi - Airi, a name that translates to "Love Jasmine," symbolizes purity, sweetness, and innocence. It represents the delicate fragrance and graceful beauty of jasmine flowers, as well as the gentle and nurturing nature of love.

Rina - Rina, meaning "Jasmine," embodies purity, sweetness, and innocence. It represents the delicate fragrance and graceful beauty of jasmine flowers, as well as the gentle and nurturing nature of love.

Kyoko - Kyoko, a name that signifies "Mirror," symbolizes reflection, introspection, and self-awareness. It represents the ability to see oneself clearly and understand one's thoughts, feelings, and motivations.

Kumiko - Kumiko, meaning "Beautiful Child," embodies grace, elegance, and inner beauty. It represents the timeless allure and charm of individuals who radiate beauty from within.

Miyuki - Miyuki, a name that translates to "Beautiful Happiness," signifies joy, contentment, and fulfillment. It represents the happiness and satisfaction that comes from living a meaningful and purposeful life.

Michiko - Michiko, meaning "Beautiful Wise Child," embodies intelligence, wisdom, and inner beauty. It represents the timeless allure and charm of individuals who possess both intellectual depth and inner grace.

Natsuko - Natsuko, meaning "Child of Summer," embodies warmth, vitality, and energy. It represents the vibrant spirit and zest for life that define the summer season.

Miyako - Miyako, a name that signifies "Beautiful Night," evokes images of serene evenings and tranquil landscapes. It captures the essence of quiet beauty and the peacefulness found in the stillness of the night.

Kazuko - Kazuko, meaning "Harmonious Child," embodies balance, harmony, and unity. It represents the interconnectedness of all things and the beauty that arises from the harmonious interplay of elements.

35 ancient Japanese neutral names along with their meanings:

Akira - Meaning "Bright" or "Clear," Akira symbolizes clarity and enlightenment.

Eiji - Eiji means "Eternal Ruler" or "Prosperous Second Son," signifying enduring leadership and strength.

Haruka - Haruka, translating to "Far-off" or "Distant," evokes a sense of exploration and adventure.

Kai - Kai means "Ocean" or "Sea," representing vastness and depth.

Kazumi - Kazumi signifies "Harmonious Beauty," embodying balance and elegance.

Kiyoshi - Kiyoshi means "Pure" or "Clear," symbolizing integrity and virtue.

Makoto - Makoto translates to "Truth" or "Sincerity," reflecting authenticity and honesty.

Michi - Michi signifies "Path" or "Road," representing the journey of life.

Nao - Nao means "Honest" or "Straightforward," embodying sincerity and integrity.

Ren - Ren signifies "Lotus" or "Love," symbolizing purity and enlightenment.

Sakura - Sakura, the Japanese word for "Cherry Blossom," represents beauty and transience.

Takumi - Takumi means "Artisan" or "Skillful," embodying craftsmanship and expertise.

Tomo - Tomo signifies "Friend" or "Companion," representing camaraderie and support.

Yori - Yori means "Trust" or "Reliability," symbolizing dependability and loyalty.

Yoshino - Yoshino translates to "Good" or "Excellent Field," symbolizing fertility and abundance.

Asuka - Asuka signifies "Tomorrow's Fragrance," representing hope and anticipation.

Haru - Haru means "Spring" or "Sunlight," embodying renewal and vitality.

Kazuki - Kazuki combines "Harmonious" and "Hope," symbolizing optimism and balance.

Kei - Kei translates to "Blessed" or "Happy," representing joy and contentment.

Noboru - Noboru means "Ascend" or "Rise," symbolizing progress and growth.

Ran - Ran signifies "Orchid" or "Storm," representing beauty and strength.

Ryo - Ryo means "Cool" or "Refreshing," symbolizing calmness and tranquility.

Sora - Sora translates to "Sky," representing freedom and boundlessness.

Tsubasa - Tsubasa means "Wings," symbolizing freedom and aspiration.

Yukio - Yukio signifies "Snow Boy," representing purity and innocence.

Arisa - Arisa means "Peaceful" or "Calm," embodying serenity and tranquility.

Hikaru - Hikaru translates to "Light" or "Radiance," symbolizing illumination and clarity.

Kaito - Kaito means "Ocean Flying," representing adventure and exploration.

Mio - Mio signifies "Beautiful Cherry Blossom" or "Sea," representing beauty and depth.

Noboru - Noboru means "Climb" or "Ascend," symbolizing progress and achievement.

Satoshi - Satoshi signifies "Clear Thinking" or "Quick Witted," symbolizing intelligence and wit.

Shin - Shin means "True" or "New," symbolizing authenticity and renewal.

Takara - Takara translates to "Treasure," representing value and significance.

Yasu - Yasu means "Peace" or "Tranquility," embodying calmness and harmony.

Yuri - Yuri signifies "Lily" or "Clever," representing purity and intelligence.

12 Most Incredible Ancient Artifacts Finds

Throughout history, astonishing artifacts have been discovered in the most unexpected of places, enriching our understanding of the past and the societies that preceded us. These remarkable finds often emerge from the mundane fabric of everyday life, reminding us that history is not confined to textbooks but surrounds us, waiting to be unearthed.

Consider the possibility that an extraordinary artifact lies dormant beneath the soil of your own garden, or perhaps tucked away in the shadows of your attic, silently holding secrets of bygone eras. It's conceivable that as you go about your daily routine, you unknowingly pass by relics of antiquity, oblivious to their significance. Indeed, the relics of civilizations past may be closer than we realize, awaiting the curious eye or chance encounter to reveal their hidden stories.

Exploring the annals of history, we uncover tales of accidental discoveries that have reshaped our understanding of the past. These serendipitous encounters, often borne out of curiosity or happenstance, have brought to light treasures long forgotten, sparking intrigue and wonder.

In this video, we delve into the captivating narratives of remarkable artifact finds, shedding light on the incredible journeys that have led to their discovery. From ancient coins nestled in the earth to forgotten manuscripts stowed away in dusty attics, each artifact tells a tale of human ingenuity, perseverance, and the enduring quest to unravel the mysteries of the past.

Archaeologists have found an extraordinary ancient monument that has the potential to reshape our understanding of history

The archaeological discovery in Marliens, France, near Dijon, has unveiled a captivating narrative of human occupation spanning multiple epochs, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the region's rich history. The site, described by the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (Inrap) as "unprecedented," features a complex arrangement of enclosures dating from the Neolithic period to the First Iron Age, each layer revealing unique insights into ancient societies and their customs.

At the heart of this discovery lies a remarkable monument consisting of three interconnected enclosures, showcasing a blend of architectural sophistication and symbolic significance. The central enclosure, boasting a diameter of 36 feet, serves as the focal point, surrounded by two smaller enclosures to the north and south. The horseshoe-shaped enclosure to the north and the partially open circular design to the south are intricately linked to the central structure, forming a cohesive ensemble whose purpose and significance intrigue researchers.