An Interview with Prof. Paul Cartledge By Richard Marranca for The Archaeologist

The Humanities are being reduced in institutions, and yet there’s a burst, a renaissance, in Hollywood and in publishing: a movie in the works, The Return (based on The Iliad), starring Ralph Fiennes as Odysseus and Juliet Binoche as Penelope, and much else. And new translations of Homer. Can you share some thoughts on this?

All human life—and, too often, death—is there in the monumental poems that we know as the Iliad and Odyssey. The latter takes its name from its eponymous hero; it’s all about Odysseus and his trials, travels, travails and tribulations. But the former poem should really be known as the Achilleid, since its theme is the rage of Greek superhero-demigod Achilles and its ultimate assuagement and abatement. We call them ‘epics’ , meaning something grand and monumental, but epos in ancient Greek meant simply ‘word’. Some word! All 27,000 or so lines between the two of them were composed orally and then much later put down in writing in a formal, hexameter metre and in a unique dialect never actually spoken by any Greeks outside of the context of a recital.

The poems are often said to be the ‘Bible’ of the ancient Greeks, but actually the (pagan, polytheistic) Greeks didn’t have any officially recognised sacred books. And although both poems are full of gods and goddesses and their interactions, both negative and positive, with humans, they are not teaching religious dogmas. What the ancient Greeks saw in the Iliad and Odyssey were rather models of mostly individual human behavior, both to imitate and to avoid, like the plague. The muthoi (traditional stories) they told remain rattling good yarns, hence the everflowing cascade of translations or versions in various languages (Emily Wilson’s not to my personal taste; see further below) and cinematic adaptations, whether on tv or in the movies (the 2003 Troy ditto). The humanities are generally under attack, yes, so there’s all the more need to defend and champion ‘Homer’!

What is the inciting incident of The Iliad? And, in a nutshell, what is the epic about?

In nuance, the theft of Helen, Queen of Sparta, by Trojan Prince Paris, a gross breach of hospitality etiquette as well as of sexual immorality, and its attempted rectification. A theft elaborately prepared by the mythic ‘backstory’ of Paris’s ‘judgment’: between the three mighty Greek goddesses Athena, Hera and sex-goddess Aphrodite, whom, naturally, the youthful Paris decides is ‘the fairest’. So it’s really Paris, not Helen who ‘causes’ the Trojan War, though later Greeks focused far more on hers than on Paris’s guilt.

Later Greeks—but not Homer, the Homer of the Iliad. He (?) plunges into the thick of it, many years later, almost ten years to be precise, after the seduction/abduction of Helen, since the action of the Iliad is confined to a few weeks, a couple of months, in the tenth year of a (historically impossible) ten-year siege. And Homer’s narrated action is focused all around Achilles and his piqued rage, which is directed chiefly at supreme Greek commander Agamemnon, King of Mycenae and brother of Helen’s cuckolded husband Menelaus.

And The Odyssey?

Discuss! As a historian specializing in early-historical Greece, I favour the view that, apart from all the excitements and sheer picaresque narrative thrills involving ogres and monsters of many kinds, it’s mainly all about Greekness or, to be more accurate linguistically, Hellenicity. (A sidebar: in Homer, Greeks are not called Hellenes but ‘Danaans’, ‘Argives’ or ‘Achaeans’.) How to be a Hellene in a world that was rapidly changing both geographically and culturally.

It’s always been a bit of a puzzle that the epic should focus on the ruler of a petty island-kingdom on the far west of mainland Greece, but I think the reason for that choice was mainly twofold: Ithaca was as far away from Troy while still being old-Greek as it was possible to get without leaving the mainland, and an ultimate western setting reflected the fact that from about the middle of the 8th century Greek traders, adventurers and settlers were moving west, some of them permanently, to south Italy and Sicily, passing by Ithaca en route.

How old were you when you first read the Iliad and Odyssey, and who were your teachers?

A. Believe it or not, I was 8 (1955). With some pocket money or birthday money, I bought and read both epics in a ‘told to the children’ format as rendered (in prose) by Jeannie Lang (daughter of Scottish poet, novelist, and literary critic Andrew) and illustrated by W. Heath Robinson (more famous as an inventor of fantastic imaginary machines). I still have the two books. Reading about the death of Argos the dog in the Odyssey reduced me to helpless tears for half an hour. 1955 was the same year I started learning Latin. I didn’t start to learn any form of ancient Greek until I was 11, and Homeric Greek not until many years later. I had no formal teachers of Homer that I can remember until I went to university, and even then I was mostly self-taught, using ‘Autenrieth’ (Georg Autenrieth, A Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges, trans. 1891) pretty much as one would try to learn ancient Greek on one’s own by using a ‘Teach Yourself Ancient Greek’ guide.

How does one teach the Iliad or Odyssey? How might one do this for students who are new to the classics?

I myself cut my homeric teeth as an Oxford undergraduate in the late 1960s, choosing to take a special option course taught by the great H. F. ‘Dolly’ Gray. At the same time as I was learning via Homer much about Greek and Near Eastern archaeology of the late Bronze and early Iron Ages, I was also’mugging up’ translations of the entirety—all 24 books—of both the Iliad and Odyssey. I cranked my reading and translating speed up to 300 lines per hour, if I remember correctly, over 50 years later. I found the latter kind of (translation) exercise less pleasurable and rewarding than the former (archeohistorical). So, pedagogically, for adult anglophone consumers, I’d recommend reading first a good, poetic translation (Prof Wilson’s will serve, even if not ideal), then immersing oneself in the ‘world’ of Homer archaeologically, then and only then, having of course first learned the letters of the ancient Greek alphabet(s), sampling a passage or two from each poem in Greek.

What do you think of Prof. Emily Wilson’s recent translation of The Iliad?

I applaud her idea of making a poetic version in principle. But if her aim is to make Homer ‘accessible’ in an equivalent version in contemporary English, albeit in metre, that aim is somewhat misplaced, even misguided. As already noted, Homer’s language is a peculiar (that is, peculiar to the epic genre) idiolect, never spoken by ‘ordinary’ Greeks in ‘ordinary’, everyday discourse. So her version of the Iliad couldn’t possibly be in any sense close to the original. In choosing ‘blank’, unrhymed iambic pentameter, she seeks not unreasonably to allude to or appeal to the example of (some of) Shakespeare, who is often related analogically to Homer in virtue of their respective cultural authority. And just as Shakespeare’s verse was that of the late 16th and early 17th century, so Wilson’s is that of the early 21st.

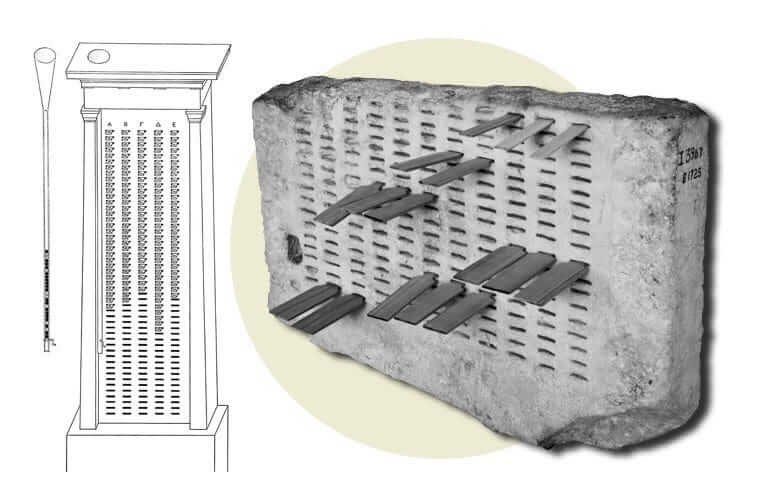

But to my ear, too much of ''Wilson's'verse'—unlike that of, say, Robert Fagles, not to mention Shakespeare—is not so much genuine poetry as prose divided up to look on the page like lines of verse. A prime quality of the Homeric original is that it is essentially oral—that is, it was thought, composed and transmitted orally over hundreds of years, in an age of universal Greek illiteracy, before being written down in the brand-new alphabetic script invented in the 8th century BCE. Orality dictated the key feature of formulae used for repeated types of actions (e.g. arming scenes) or repeated personal epithets; these are not so hard to reproduce. Much harder is to capture the urgent immediacy of orality for a totally different modern audience—or rather, readership.

I recall that Professor Wilson said that one way she began translating The Odyssey was to begin playing around with the Cyclopes’ chapter, to get a feel for that through the vivid character, action, violence, etc.

Before Prof Wilson became the first woman to translate the Iliad into English, she had ‘done’ an excellent Odyssey, not the first by a woman, but it rightly received many plaudits. The subject-matter of that poem, so it seems to me, lends itself more to non-poetic exposition than does that of the Iliad. The Cyclopes episode, a sort of challenge match between the semi-divine monster Polyphemus and the all-too-human Odysseus, was an excellent choice of starting-point for Prof. Wilson for all those reasons (vivid character action, violence—often spine-tingling, even horrific). The episode has had multiple, often clashingly incongruous resonances in subsequent western literature and visual arts, as was brilliantly demonstrated by Mercedes Aguirre and Richard Buxton in their recent Cyclops: The Myth and its Cultural History (Oxford U.P., 2020).

I recall that in The Odyssey, she didn’t use the term “whores” for the women who had sex with the Suitors; she used the term “slaves.” That’s a big difference, isn’t it?

A. Yes, and no! In the ancient Greek (and Roman) world, many sex-workers were enslaved persons, so for females, the two terms ‘whores’ and ‘slaves’ would regularly have been semantically congruent. The poet or poets of the Odyssey made it abundantly clear that the female royal-household servants of Penelope and her son Telemachus were unfree and belonged to them, that is, were slaves. That they could also be regarded as ‘whores’ derived from the fact that they slept with—or were required to sleep with—some or all of the 108 suitors competing for the hand (and more) of the supposed widow of Odysseus, young men whose general lack of social finesse encompassed that particular mode of abusive sexual behaviour.

Professor Wilson’s Iliad begins thus: “Goddess, sing of the cataclysmic wrath of great Achilles, son of Peleus…”And The Odyssey: “Tell me about a complicated man.”

A. To my ear, ‘complicated’ is both somewhat bathetic, for the opening line of an epic, and somewhat anachronistic. The Homeric Greek epithet polutropos means literally ‘much-turning’ or ‘of many turns’, which can be interpreted rather flatly, as is done by Prof Wilson, or be given a knowing spin as in ‘of many wiles’, for Odysseus is above all—or much—else wily. ‘Cataclysmic’ is a great epithet, also knowing since Achilles’s rage or wrath will cause cataclysmic, though not always fatal, damage both to personal relationships among Greeks and to the Greeks’ supposed cause. But it’s not actually there in Homer’s Greek, so it’s translator’s license.

In the Translator’s Note to The Iliad, Professor Wilson writes: “Human mortality is at the center of it all.” The Iliad is about many things, such as families, the hero, war, fate, the gods, Achilles’ anger and so on, but is mortality the umbrella or DNA of the epic?

This is surely correct: the humanities are by definition concerned with humankind’s life-chances and life-fates, and mortality captures humanness from one essential viewpoint: we humans all inevitably die. For the ancient Greeks, the gods and goddesses were precisely the not-mortals, a-thanatoi. Mortality is there in both poems: hundreds of Greeks and Trojans die in the Iliad, and all Odysseus’ men are gone before the hero regains Ithaca. But it is not the umbrella concept of either poem, though it is far more so in the Iliad than in the Odyssey. Odysseus, after all, lives literally to tell his tale—or (often tall) tales. As for Achilles, he is still very much alive and kicking at the end of the Iliad; his death will not be related until later, in a poem of the so-called Epic Cycle.