From the foothills of Pindus to the coasts of Asia Minor, ancient Greeks often encountered peculiar findings in the ground: enormous bones, dentitions, and skulls. These remnants, which we now recognize as fossils of prehistoric animals, inspired some of the most enduring myths of the Greco-Roman world. But how did the ancients interpret these findings? What role did they play in their political, religious, and cultural life?

Researcher Adrienne Mayor, in her seminal work The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times, explores this very question, connecting ancient texts, mythological traditions, and geological evidence to argue that the ancients were, in essence, the first paleontologists.

Pausanias and the Bones of Heroes

One of the primary chroniclers of such findings is Pausanias, a 2nd-century AD traveler whose work Description of Greece offers invaluable insights into the religious and mythical landscapes of antiquity. In numerous accounts, Pausanias mentions discoveries of "gigantic bones," attributed to heroes like Orestes and Theseus or even mythical creatures like giants and cyclopes.

For instance, when describing Tegea, Pausanias notes that the Spartans exhumed massive bones they identified as Orestes', following an oracle from Delphi. Upon returning to their homeland, they used these remains as religious and political symbols of victory over the Arcadians.

The Transportation and Politicization of "Relics"

The act of transporting heroic bones wasn't merely an honor to ancestors; it carried political intent and ideological weight. The relocation of Theseus' bones from Skyros to Athens by Cimon in 475 BC bolstered Athens' political unity and democratic resurgence under Pericles.

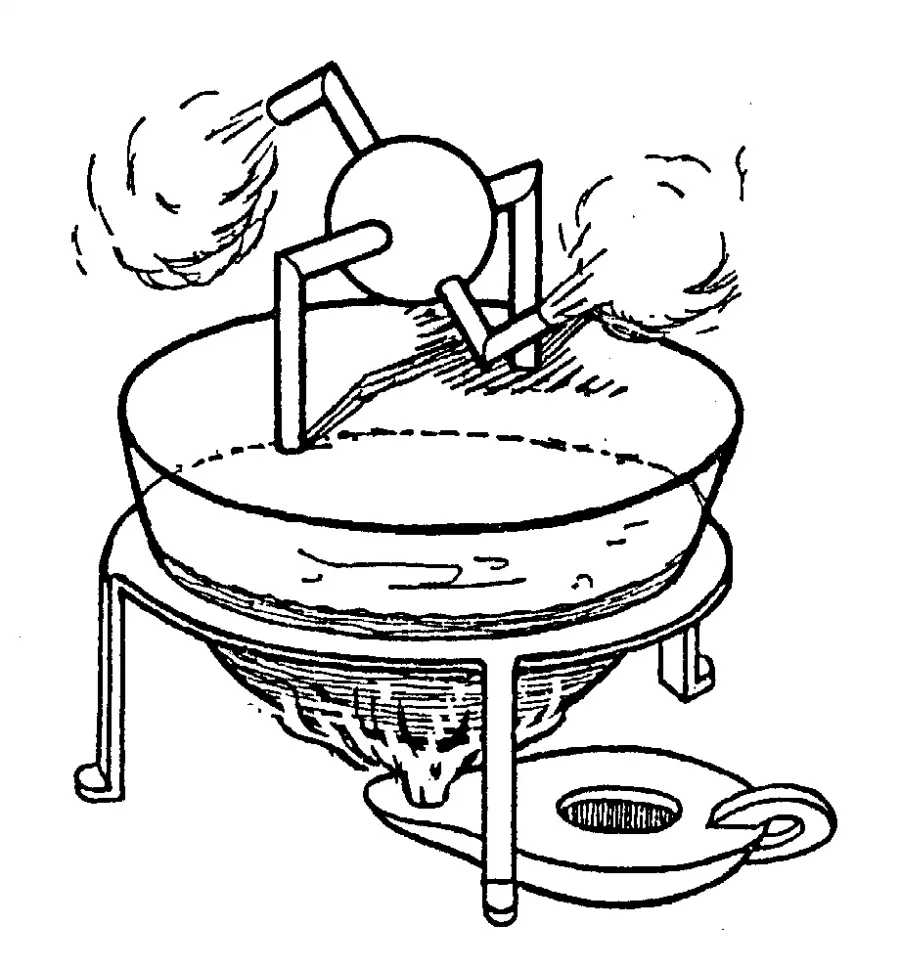

map by Michele Mayor Angel, Mayor 2000: 114, Mar 3.1

Adrienne Mayor highlights the use of these findings to "legitimize" a city's dominance or to fortify collective identity. They served as evidence of genealogical ties to the heroic age, justifying political ambitions or military interventions.

Herodotus and the Tradition of "Tribal" Memory

While Herodotus doesn't frequently mention specific bones, his Histories incorporate numerous local narratives that seem to stem from natural discoveries. Descriptions of "monstrous" beings, such as the griffins in Scythia, might have originated from fossils of prehistoric mammals unearthed by gold miners in those regions.

How Did the Ancients Explain Fossils? Explaining the Bones: Myth as Natural History

For ancient Greeks, there was no clear distinction between science, mythology, and theology. Observing a massive femur could reasonably lead to the belief that it belonged to a Giant or Titan. Legends of the Gigantomachy or Titanomachy might be mythological "memories" of a prehistoric world dominated by colossal beings.

The Trojan Monster as it is depicted on an ancient Greek vase, housed at the Mu seum of Boston

In areas like Lesbos and Samos, locals believed fossils were remnants of wars between gods and heroes. On Chios, a fossil was attributed to Ajax the Telamonian, while in the Aegean islands, "the shoulders of giants" were often depicted in public rituals or housed in temples.

Adrienne Mayor and the Modern Reinterpretation of Myths

Mayor's significant contribution lies in crediting the ancients with observational skills and rationality. In her book, she presents numerous examples where Greeks not only interpreted these bones but also integrated them into a natural history of the world. She attributes to them an early form of scientific thinking: recognizing that the world was once inhabited by different species.

Mayor compares ancient findings with modern paleontological analyses, noting that many regions mentioned in texts, like Tegea and Skyros, indeed contain fossils of large mammals from the Pleistocene. The bones considered to be Orestes' might have been remnants of mammoths or other megafauna.

The Trojan monster could correspond to the skull of Samotherium. The picture of the vase is taken from Mayor (2000) and the drawing of Samotherium from Lydekker(1883).

From Myth to Natural Interpretation: The End of "Fantasy"?

Modern archaeology and paleontology, aided by geology, validate the ancients' intuition to some extent. Rather than being naive or pre-scientific, ancient Greeks emerge as observers of the natural world with creative thinking. The connection between natural findings and mythological tradition was their way of understanding and interpreting the inaccessible past.

Fossils in ancient Greece weren't merely "lifeless remnants"—they were carriers of stories, foundations of myths, evidence of divine presence, and tools of political dominance. Adrienne Mayor's work is invaluable, allowing us to view the ancients not only as myth-makers but also as proto-scientists striving to decipher the Earth's signs, much like we endeavor to interpret their writings.

This dialogue between the natural world and cultural memory is perhaps the most authentic form of "paleontology": not just about what happened, but about how people interpreted it.