The impressive wooden model representing the Palace of Knossos during the Neopalatial period (1750 BC–1450 BC) at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum is the work of Zacharias S. Kanakis, conservator of the Archaeological Society of Athens, 1968.

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Crete, Greece, is home to one of the world's most impressive representations of the ancient Minoan civilization. Among its wide array of historical artifacts and exhibits, one item stands out remarkably for its exquisite craftsmanship and historical significance: the wooden model of the Palace of Knossos. Depicting the edifice during the Neopalatial period (1750 BC–1450 BC), this model provides us with an incredible visual journey into the world of our distant past.

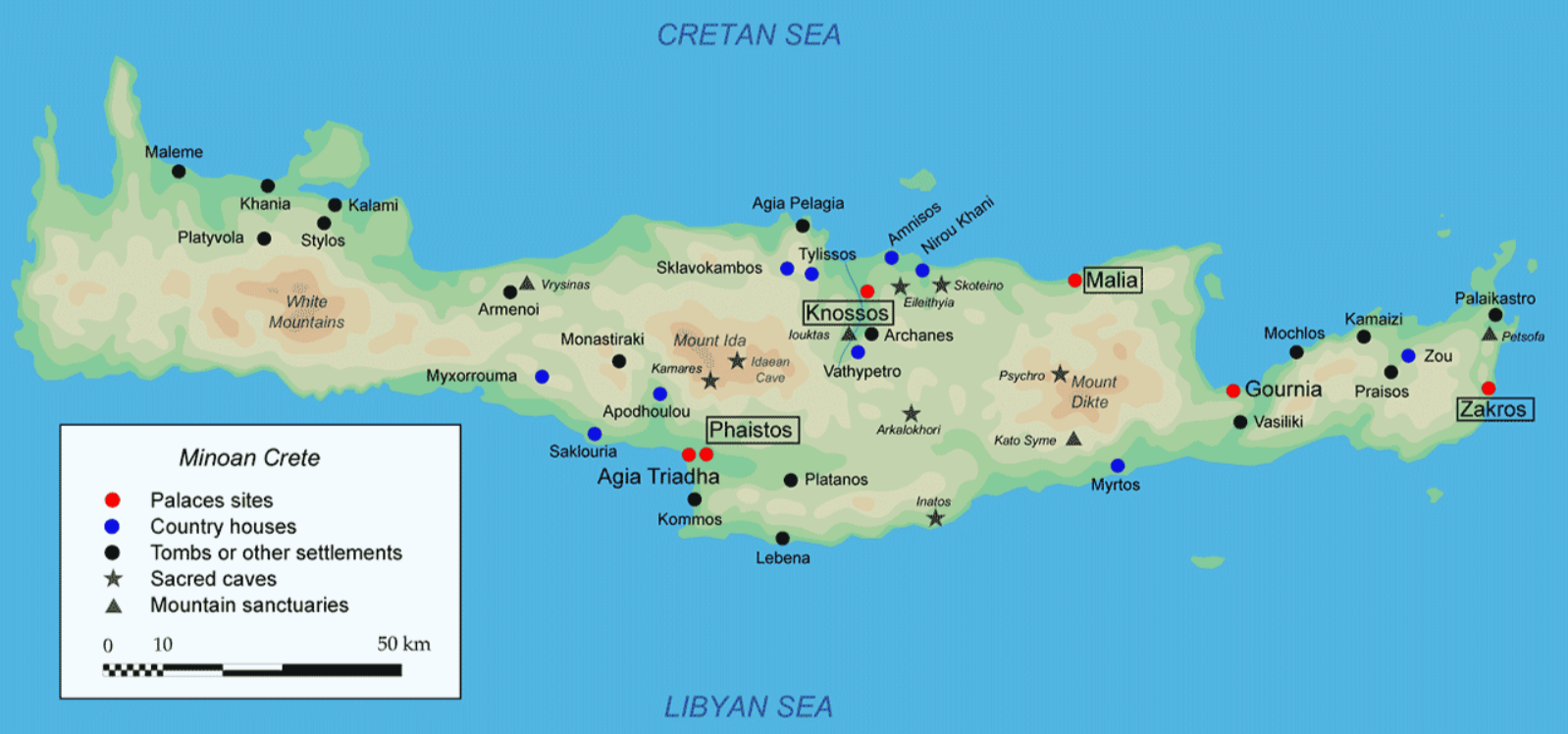

Knossos, the center of Minoan civilization, was an intricate complex believed to be the mythical labyrinth of King Minos, housing the terrifying Minotaur in Greek mythology. The palace, a vibrant manifestation of the high point of Minoan architecture, culture, and power, sprawled across an area of approximately 22,000 square meters. It was characterized by its complex labyrinthine layout, extensive storerooms, grand courtyards, and vibrant frescoes.

The wooden model in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum vividly brings this architectural marvel back to life. It painstakingly replicates every minute detail of the palace, from its meandering passageways and grand courtyards to its royal apartments and sanctuaries. This representation does not merely rest on aesthetic considerations; it represents an archaeological accomplishment. The model has been designed based on extensive archaeological findings and studies of the site, making it an accurate depiction of the Palace of Knossos as it would have stood in its heyday.

What makes the model so striking is its intricate attention to detail, which captures the complexity and grandeur of the palace. It shows the innovative architectural characteristics of the Minoans, such as light wells, multiple levels, and open-air courtyards. The miniature version of the grand staircase, which leads to the royal apartments, draws particular attention. Furthermore, it depicts the various chambers, including workshops, storerooms filled with massive pithoi (storage jars), and the Throne Room, highlighting the palace's multifaceted functionality.

The model also does an excellent job of showcasing the Minoan's affinity for nature and their ingenuity in integrating it into their structures. The palace was designed around a central courtyard, as shown in the model, and had many open areas and porticoes that allowed sunlight to pour in, a characteristic feature of Minoan architecture.

The representation is mainly based on the ruins of the second phase of the new palace, which date to the 16th century BC. The palace of Knossos is divided into several sections, each of which has a separate use. It was multi-story, built with hewn buildings, and decorated with magnificent frescoes that probably depicted religious ceremonies. Access was through three entrances located on its north, west, and south sides. Four wings develop around the central courtyard. Thus, on the west side of the palace, there are concentrated the ceremonial rooms on the upper floors, the public storerooms (18 long, narrow rooms) with the large jars, the sanctuaries, and the treasuries, as well as the throne room consisting of the vestibule and the main throne area. In the south-west part of the palace are the Western Court and the Western Entrance leading to the Corridor of Pompeii, which was decorated with frescoes ("Prince with the Lilies"). On the left side of the corridor are the Propylaia and the famous Double Horns (Dedication Horns), one of the sacred symbols of the Minoan religion. The first excavations in the area of Knossos were carried out in 1878 by the merchant Minoas Kalokairinos.

Visitors to the museum are invariably drawn to this mesmerizing display. They marvel at the sheer scale and intricacy of the Palace of Knossos, brought to life through the meticulous work of the creators of this model. This wooden marvel serves as a tangible link to our shared past, providing insight into a civilization that continues to captivate us centuries after its decline.

The wooden model of the Palace of Knossos at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum is not just a detailed replica; it's an architectural narrative that takes us back in time. It is a testament to the extraordinary civilization that the Minoans were, their advancements in architecture, their deep-seated respect for nature, and their artistic expressions, all rendered in exquisite detail. This immersive experience serves as a reminder of the fascinating journey of human civilization and the wonders that our ancestors were capable of creating.