No other artefact surviving from the Anglo-Saxon era embodies so many rich resonances as the Alfred Jewel. It is a matchless piece of goldsmith's work by a master-craftsman operating under the patronage of the West Saxon court. The Jewel represents the pinnacle of Anglo-Saxon technological achievement, while the name of the monarch which it proclaims places it among the most precious of royal relics.

The Jewel came to light in 1693, ploughed up in a field at North Petherton, Somerset. Even its find-spot contributes to its interest, since North Petherton is only a few miles from Athelney Abbey, the stronghold in the marshes from which Alfred launched his counter-attack on elements of the Great Army of the Danes. This attack ultimately led to his crucial victory at Edington in 878. The Ashmolean's registers record its presentation in 1718 to the Museum, where it has formed one of the principal treasures of the collection ever since.

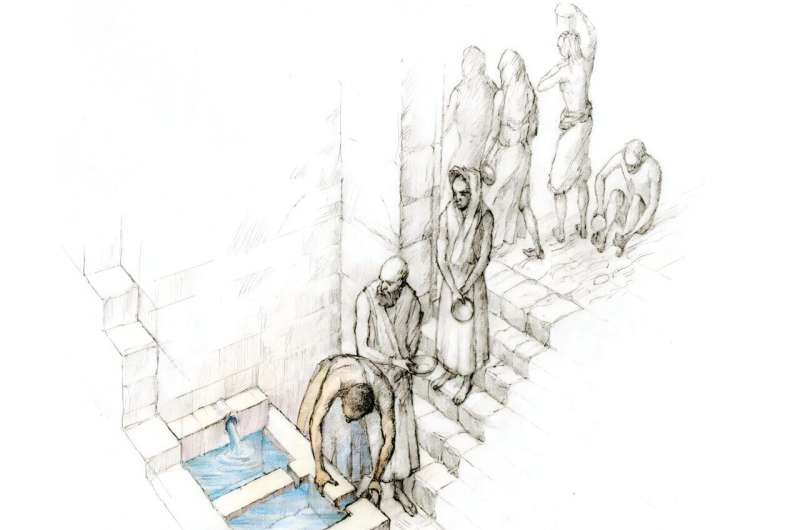

Over the years the Jewel has been the cause of as much speculation as admiration. Precisely what might have been its purpose was a source of much uncertainty: early theories suggested that it might have been the centrepiece of a royal headdress - literally a crown jewel - but the setting seemed inappropriate for that purpose. An alternative, that it was a pendant to be worn round the neck, seemed equally unhappy since it would have condemned the figure on the Jewel to have hung permanently upside-down. More recently opinion has moved towards its being an aestel or pointer, used to follow the text in a gospel book in much the same way that the Yad continues to be used in the Jewish synagogue for reading the Torah. The dragonesque head at the base of the Jewel holds in its mouth a cylindrical socket, within which the actual pointer - perhaps made of ivory - would have been held in place by a rivet (still in situ).

Similarly curious is the teardrop-shaped form of the piece. Current opinion suggests that the Jewel was formed around a pre-existing slab of rock-crystal, possibly a re-used Roman piece.

The figure represented in delicate colours in cloisonné enamel, on a plaque protected by the rock-crystal, is also enigmatic. Originally it was interpreted as St Cuthbert, the best-known English saint of the pre-Alfredian period, but it is now thought to represent the sense of sight: a contemporary silver brooch in the British Museum, engraved with figures representing all five senses, shows sight as a man holding two prominent plant-stems or flowers, exactly as on the Alfred Jewel. Such an allusion would be entirely appropriate for an instrument dedicated to the practice of reading.

And finally the inscription: AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN - 'Alfred ordered me to be made'. No one has ever doubted that the sponsor of the piece was King Alfred the Great. He died in 899 after turning the tide of battle against the Scandinavian warriors who threatened the continuing existence of Anglo-Saxon control over much of England. The West Saxon flavour of the prose is entirely in sympathy with such an interpretation. Alfred's achievements were as much cultural as military, and amongst his most effective measures was his commissioning of translations of religious texts into the vernacular. With each of the copies of one of these texts - the Pastoral Care of Pope Gregory the Great, written c.890 - which he dispatched to monasteries throughout England, he is said to have sent also a precious aestel so that it might be read with all due solemnity.

Although less impressive than the Alfred Jewel, the Minster Lovell Jewel, dating from the late ninth-century, shares many of its characteristics: the use of granulation as decoration appears on the surfaces of both pieces, while the fine enamelling technique (which is also a feature common to both) is extremely rare elsewhere at this time. The likelihood is that both pieces were made in the same workshop. The socket at the base of the Minster Lovell Jewel, which retains a rivet like that on the Alfred Jewel, also suggests that they performed the same function as a pointer.

Both jewels are on display in the ‘England 400-1600’ gallery on the second floor.

Replicas of the Alfred Jewel were made around 1901, in celebration of the millenary of King Alfred's death. Some were made by Payne's of Oxford and others by Elliot Stocks of London, but no records survive for either of these companies from this period. A few replicas were later made by the Ashmolean's conservation department.