In the East Riding of Yorkshire, an archaeological endeavor linked to a modern infrastructure project unearthed astonishing elements from the past, shedding new light on Roman Britain and even earlier periods of human occupation. Among the finds were parts of a previously unknown Roman road, a small circular burial monument with human remains, and a 'burnt mound”—each offering a unique glimpse into ancient life and practices.

The finds came to light during preparatory works for a new Yorkshire Water sewer project near the new Full Sutton prison and Stamford Bridge, extending over three-and-a-quarter miles. It's a testament to the practice of conducting archaeological assessments in areas of historical interest before the commencement of construction projects. This proactive approach led to the revelation of these significant archaeological features, with the earliest potentially dating back 4,500 years.

The Roman road discovered near Stamford Bridge, notable for its drainage ditches, is believed to have stretched northwards towards the ancient settlement of ‘Derventio Brigantium,’ near modern-day Malton. This road, hitherto unknown, marks an important addition to our understanding of Roman Britain's infrastructure, suggesting a more extensive network of Roman roads in Yorkshire than previously documented.

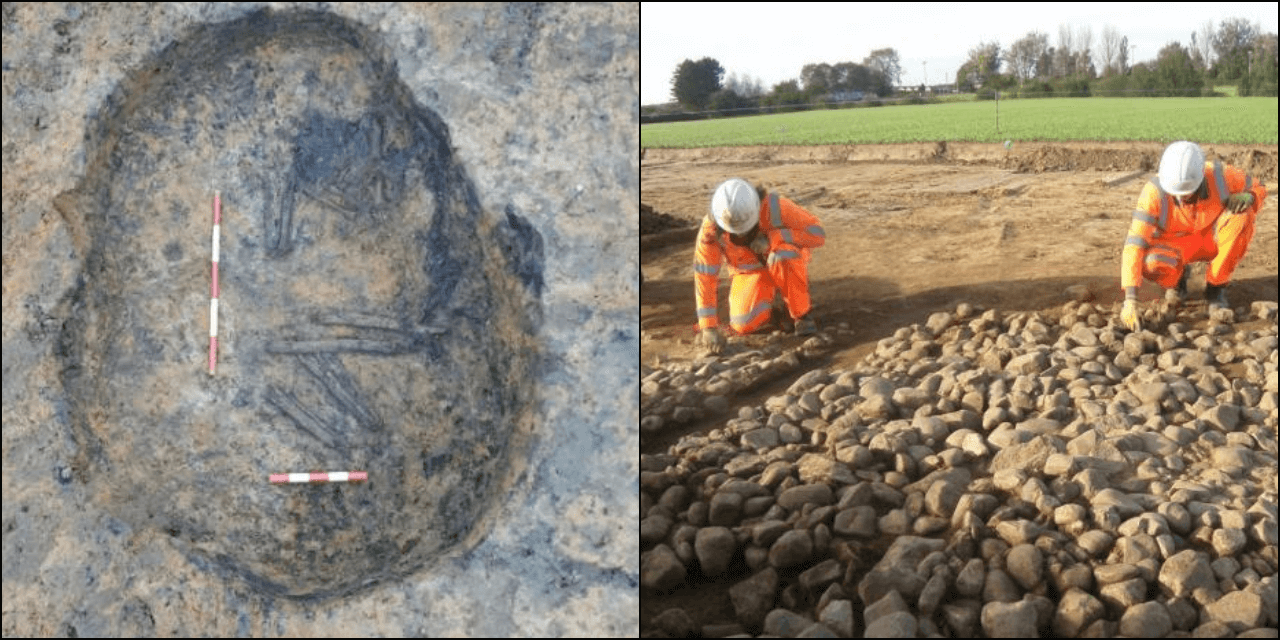

The foundations of the previously unknown Roman road (Image: Yorkshire Water)

Close to this road, a small circular burial monument was unearthed, harboring human remains that, despite historical disturbances from ploughing, were remarkably well-preserved. The preservation of these remains, surprising given the local sandy geology's acidic nature, was attributed to the grave's backfill—a mixture of burnt stone and charcoal from an adjacent 'burnt mound.' This method seemingly counteracted the acidic conditions, allowing the bones to survive through the millennia. Interestingly, no artifacts were found within the grave, suggesting that the burial practices at this site might have eschewed the inclusion of grave goods, or perhaps the grave was subjected to ancient looting.

The third find, referred to as a 'burnt mound,' is particularly intriguing. These mounds, composed of burnt stone and charcoal, are not commonly found in lower-lying lands, and their purpose remains a subject of speculation among archaeologists. The proximity of this mound to the burial site might indicate a ritualistic or functional relationship between the two, offering fascinating insights into the cultural practices of the era.

The ancient human remains found at Full Sutton (Image: Yorkshire Water)

These discoveries, beyond their immediate historical and archaeological significance, underscore the importance of integrating archaeological investigations with modern development projects. Each find contributes valuable data to our understanding of ancient life in Britain, opening new avenues for research and study. The project, as highlighted by Yorkshire Water project manager Adam Ellis, reflects the enriching collaboration between development and preservation, allowing for the advancement of modern infrastructure while honoring and exploring our ancient heritage.

This trio of discoveries in Full Sutton not only enriches our knowledge of Roman and prehistoric Britain but also serves as a poignant reminder of the layers of history that lie just beneath our feet, awaiting discovery. As the sewer project proceeds, one can only hope that it, and others like it, will continue to reveal the hidden chapters of human history embedded in the landscape.