Once thriving centers of power and culture—rivals in prestige and influence to ancient Athens and Rome—these legendary cities mysteriously disappeared from the face of the Earth for centuries. Their stories, once lost to time, now echo with both wonder and tragedy.

Pompeii

Though the tragic fate of Pompeii has been told countless times, for centuries the world had forgotten about this once-splendid Greco-Roman city. Home to a bustling forum, a grand amphitheater, lavish villas, and residential buildings dating back to the 4th century BCE, Pompeii was a marvel of urban life.

A private bath recently discovered at the archaeological site of Pompeii.

Around midday on August 24, 79 CE, Mount Vesuvius erupted with apocalyptic force, burying the city under a thick layer of volcanic ash and pumice. For nearly 1,700 years, Pompeii remained entombed, untouched and unknown—until 18th-century excavations revealed a city eerily frozen in time.

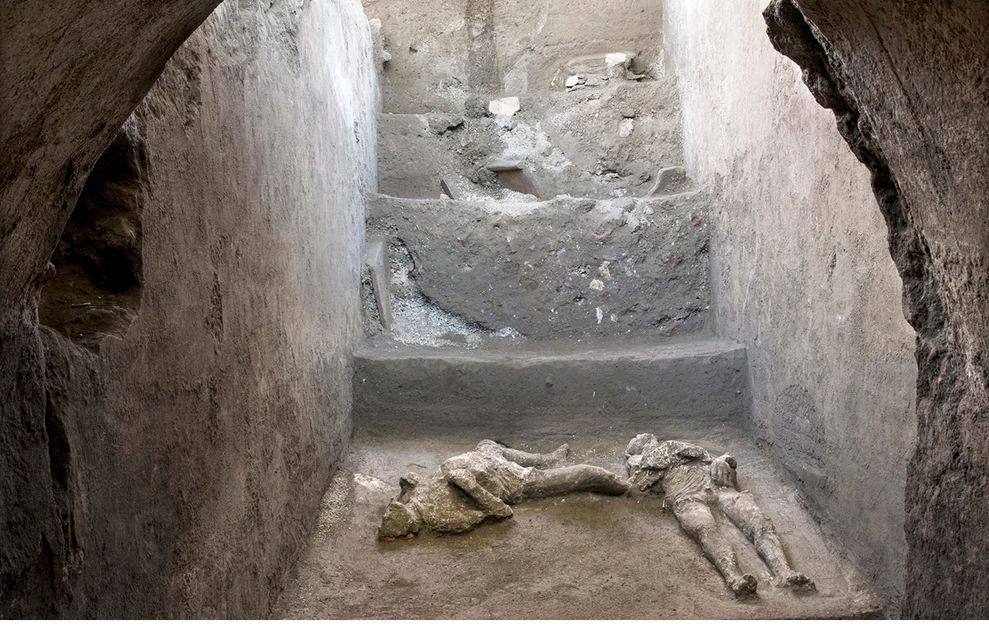

A wealthy man and his slave

Inside the buildings, archaeologists uncovered the well-preserved remains of people who had tried to flee the eruption, along with everyday items like loaves of bread still in ovens—offering a haunting snapshot of life as it was in that final moment.

The city’s earliest known historical reference dates back to 310 BCE, during the Second Samnite War, when a Roman fleet landed at Pompeii’s port on the Sarno River and launched an unsuccessful attack on nearby Nuceria. Over time, Pompeii was absorbed into the Roman Republic and played a significant role in several military campaigns.

According to the historian Tacitus, tensions ran high in Pompeii, including a notorious riot at the amphitheater in 59 CE between residents of Pompeii and Nuceria. Just three years later, a powerful earthquake struck, causing widespread destruction. The city was still recovering when, 17 years later, it met its final and devastating end.

Troy

A replica of the legendary Trojan Horse at the entrance of the archaeological site of Troy.

The legendary city of Troy was long believed to be the stuff of myth, its precise location a mystery despite references in works by Homer, Herodotus, and Strabo. But between 1870 and 1890, German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann led extensive excavations at Hisarlik, a hill in modern-day Turkey, where he unearthed the remains of what appeared to be a fortified citadel known in antiquity as Ilium.

At the site, archaeologists discovered nine major settlement layers, each representing a different period of construction, habitation, and eventual destruction—starting around 3000 BCE.

By around 700 BCE, Greek settlers had moved in, renaming the area Ilium. In 85 BCE, the Romans sacked the city, but it was later partially restored by Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Under Emperor Augustus, Ilium flourished again, with grand public buildings and renewed prestige. However, according to Britannica, after the founding of Constantinople in 324 CE, the city began to decline and eventually faded from memory.

Carthage

According to legend, Carthage was founded by Phoenician settlers from Tyre in 814 BCE—on a triangular peninsula near what is now Tunis, Tunisia. Surrounded by low hills and a natural harbor, the city's strategic location made it a hub of commerce and power.

The wealth of Carthage became the stuff of legend. In the 5th century BCE, Herodotus described how the Carthaginians traded with the indigenous peoples of North Africa:

Depiction of the ancient city of Carthage.

“They unload their goods and arrange them on the shore. Then they return to their ships and light a fire. The natives approach, leave gold in exchange for the goods, and move away. The Carthaginians return, and if the gold seems a fair price, they take it and sail off. If not, they wait until more gold is offered.”

By the mid-3rd century BCE, Carthage clashed with Rome in the Punic Wars. In 146 BCE, the city was utterly destroyed, looted, and burned—fulfilling the infamous decree of Roman senator Cato the Elder: "Carthago delenda est"—Carthage must be destroyed.

Despite its ruin, Carthage rose again. Rebuilt by Julius Caesar and later made the administrative center of the Roman province of Africa by Emperor Augustus in 29 BCE, it regained some of its former grandeur.

Yet its decline was inevitable. In 439 CE, Genseric, king of the Vandals, sacked the city. Nearly a century later, in 533 CE, Byzantine general Belisarius entered Carthage without resistance, following his victory over the last Vandal king. The Arab conquest in 705 CE finally marked the end of Carthage’s relevance, as the nearby city of Tunis rose in its place.

Atlantis

From Hollywood films and video games to literature and fine art, the lost island of Atlantis remains one of the most enduring mysteries of antiquity.

According to ancient Greek and Egyptian sources, Atlantis was said to lie in the Atlantic Ocean, west of the Strait of Gibraltar. The story’s most famous origins come from Plato’s dialogues, Timaeus and Critias.

In Timaeus, Plato recounts a tale passed from Egyptian priests to the Athenian lawmaker Solon. They described a powerful island—larger than Asia Minor and Libya combined—that once dominated much of the Mediterranean world.

Ruins of the Antonine Roman baths in Carthage.

Roughly 9,000 years before Solon’s time, Atlantis was a wealthy empire ruled by mighty kings. After conquering many nations, the Atlanteans grew corrupt and defied the gods. As punishment, a series of earthquakes and floods sent their island plunging beneath the sea.

In Critias, Plato imagines Atlantis as an ideal state—perhaps more political allegory than historical account. Nevertheless, many medieval writers took the story literally, and theories about Atlantis’s reality continue to stir debate.

Britannica suggests that, if not a complete invention by Plato, the tale may echo Egyptian records of the volcanic eruption on the island of Thera (Santorini) around 1500 BCE, an event that devastated Minoan civilization and could have inspired the myth.

A Pattern in the Mediterranean

Depiction of Atlantis

What’s striking is how many of these lost powerhouses of civilization—Pompeii, Troy, Carthage, and possibly even Atlantis—are rooted in the Mediterranean basin, once the beating heart of the ancient world.

Countless other ancient cities, mentioned in texts and oral histories across the globe, still lie buried or undiscovered. Their ruins may one day surface—offering new glimpses into the rise, fall, and rediscovery of humanity’s most extraordinary civilizations.