Researchers from Charles University in Prague and Vrije Universiteit in Brussels, along with members of a multidisciplinary team from various Austrian institutions, have discovered that it is possible to obtain detailed information about people who were cremated thousands of years ago. The team examined the bones of two Bronze Age persons found in an urn in their study, which was published on the open-access website PLOS ONE.

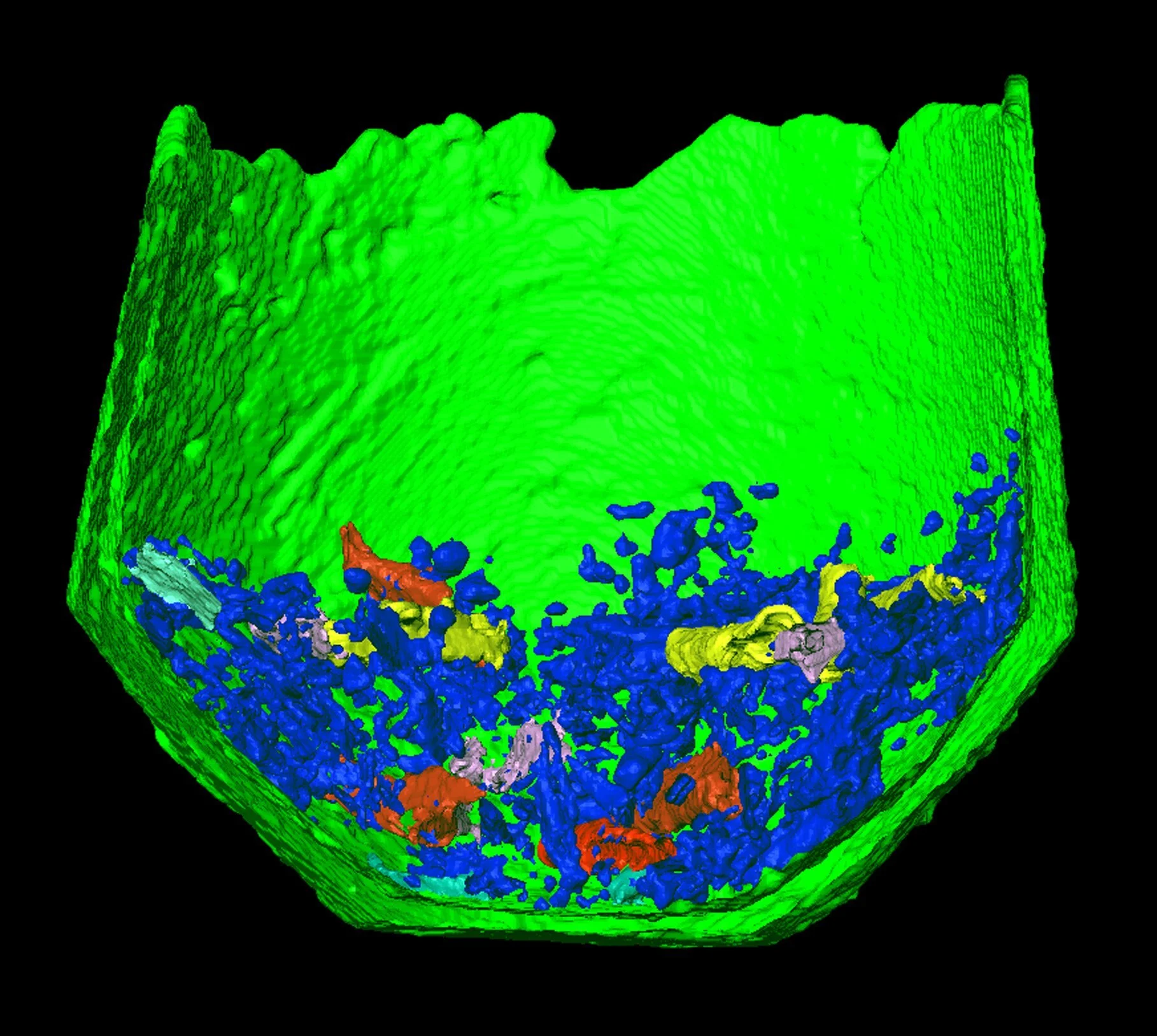

Cross section through Urn 2. Different colorations represent identified bone fragments based on the CT scans. Credit: Lukas Waltenberger, CC-BY 4.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Inhumation and cremation were the two main burial practices used during the Bronze Age, according to previous studies. In the former, a pit was typically dug for one or more people, whose remains were then deposited within, and the grave was then filled with earth, rock, or other material. In cremations, the bodies were burned, usually on a pyre. The bones were then typically placed in an urn and either stored or interred. It was extremely typical in both situations for additional stuff to be buried or burned beside the deceased person.

Due to the quantity of bone material, archaeologists have often found it to be a very simple undertaking to learn about inhumations. It has been more difficult to learn more about those who were cremated. The researchers used a fresh perspective in their latest endeavor and discovered that there is much more to be discovered from these remnants.

The group looked at two Bronze Age urns that were discovered in Austria in 2021. Both were thought to be the final resting place of a single person and neither had been disturbed. The researchers employed a number of methods and instruments to uncover more information about the people whose remains were kept in the urns.

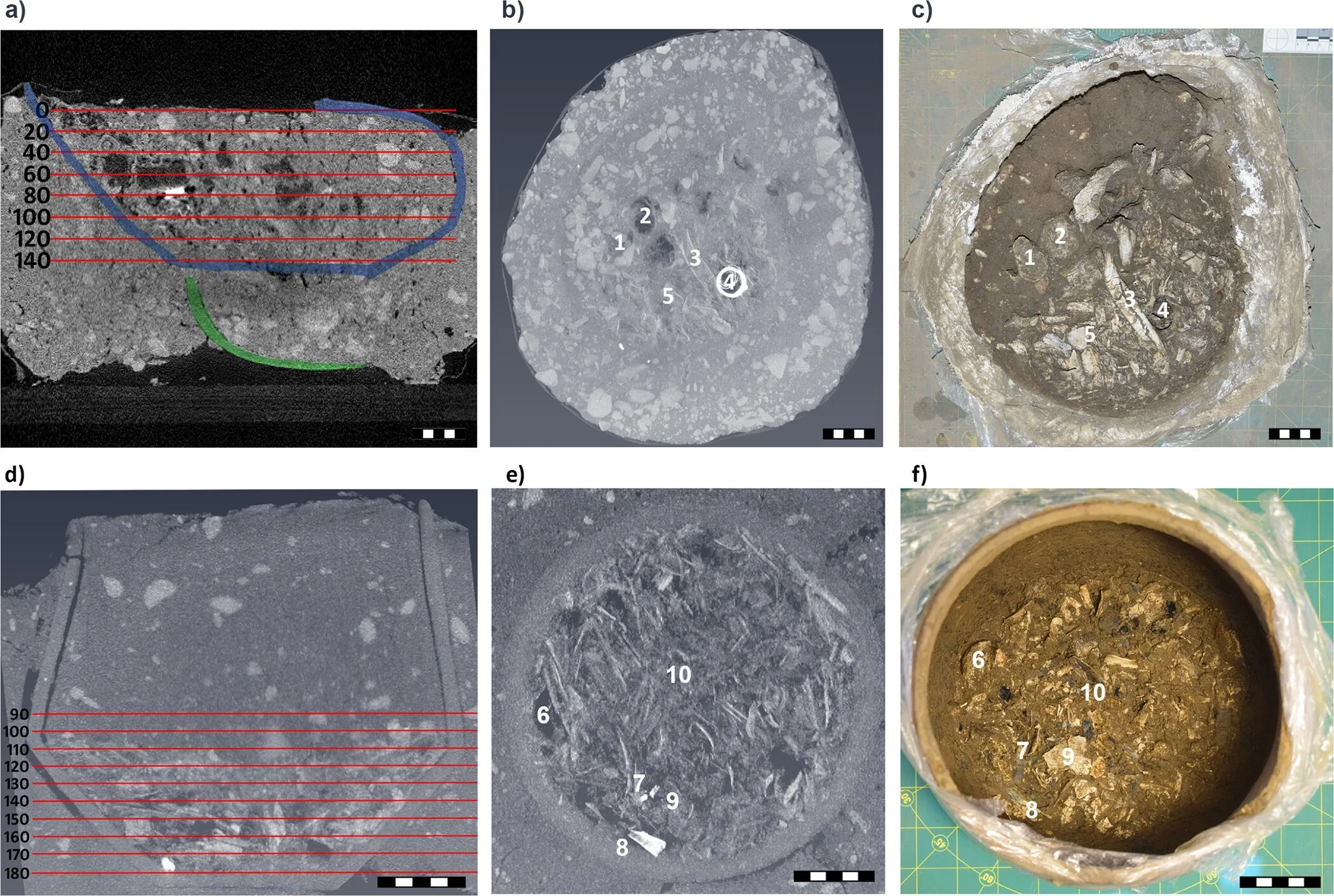

Using the first technique, CT scans were performed on the urns to determine their contents and their location without disturbing them. The researchers then used conventional isotopic, geochemical, zooarchaeology, anthropology, and archaeobotanical testing procedures.

a) mid-sagittal section of Urn 1 with arbitrary excavation layers, b) MIP-projection of layer 80, c) photo of layer 80 during excavation, d) mid-sagittal section of Urn 2 with arbitrary layers, e) MIP-projection of layer 150, f) photo of layer 150 during excavation. The numbers represent identifiable structures in b) and c) or e) and f): 1) lumbar vertebra, 2) femoral head, 3) humerus diaphysis, 4) bronze wire and pendant, 5) cranial fragment, 6) humerus head, 7) bronze spirals, 8) bronze sheet, 9) cranial fragment, 10) tibial fragment. Scale length is 5 cm. Credit: PLOS ONE (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289140

The discovery of bone fragments in both urns confirmed that, as predicted, each contained the remains of a single person. Both people were female, one between the ages of 9 and 15, the other in her early 20s. Both had resided in what is now St. Pölten for the majority, if not all, of their lives.

They were both wearing bronze jewelry and had been burned on a fire with meat from other animals. The younger daughter was also discovered to have a vitamin deficit, which suggests she was sick before she passed away. Additionally, both urns showed signs of plant matter that was probably utilized as a fire starter.

The method developed by the scientists might be applied to additional cremated human remains from the Bronze Age or from later eras to learn more about them.