A recent archaeological discovery in France may represent the world’s oldest known three-dimensional map. This remarkable find, identified in the sandstone rock shelter known as Ségognole 3, lies south of Paris and is estimated to be around 13,000 years old.

A Unique Discovery in Prehistoric Rock Shelter

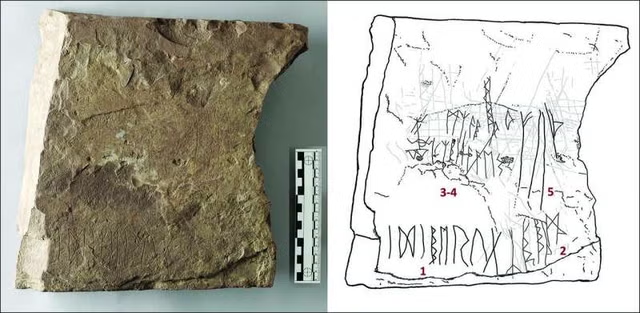

Ségognole 3 has been known since the 1980s for its prehistoric engravings, including depictions of two horses flanking what researchers describe as a “sexual figuration,” possibly symbolizing fertility. However, a recent study published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology has revealed another significant feature at the site—a meticulously engraved floor that appears to be a miniature representation of the surrounding landscape.

This discovery suggests that early humans may have created a three-dimensional model of their environment, making it one of the earliest known attempts at cartography.

A Paleolithic Model of the Landscape

The Paleolithic era, or Old Stone Age, spans from approximately 3.3/2.5 million years ago to around 12,000 years ago. During this period, early humans developed tools and artistic expressions that provide insight into their cognitive abilities.

According to the study, the engraved floor at Ségognole 3 appears to depict the natural water flows and land formations of the region. Rather than a map in the modern sense—with precise distances, directions, and travel times—the engraving seems to illustrate the way water moves through valleys, converges into rivers, and forms lakes and wetlands.

Study author Anthony Milnes, from the University of Adelaide’s School of Physics, Chemistry, and Earth Sciences, emphasized the importance of this representation for Paleolithic peoples. “For early humans, understanding water flow and recognizing landscape features would have been far more crucial than measuring distances and travel times as we do today,” Milnes explained.

He further noted that their research demonstrates how humans modified the hydraulic behavior in and around the shelter, modeling natural water flows in a way that showcases the engineering knowledge and imagination of prehistoric societies.

Human Influence on Natural Water Flow

Lead researcher Médard Thiry, from the Mines Paris – PSL Center of Geosciences, made the discovery after noticing fine-scale morphological features that appeared to be deliberately shaped rather than naturally formed. This suggests that prehistoric humans intentionally sculpted the sandstone to direct rainwater and control water flow patterns.

“Our findings indicate that Paleolithic people engineered the rock surface to guide water infiltration and runoff, a concept that had not been previously recognized by archaeologists,” Thiry stated.

A Possible Mythological Significance

Beyond its practical function, researchers believe the engraved floor and its connection to water may hold a deeper, symbolic meaning. The hydraulic installations—both the sexual figuration and the miniature landscape—are located just two to three meters apart, suggesting a potential link in their significance.

“The meaning behind these features is likely tied to early conceptions of life and nature,” Thiry added. “However, their full symbolic significance remains beyond our reach.”

A Groundbreaking Insight into Early Human Cognition

This discovery sheds new light on the cognitive abilities of early humans, highlighting their understanding of the environment and their ability to represent it in three dimensions. If confirmed as a map, this engraving could challenge existing theories about the origins of cartography and early human interaction with the landscape.