The world’s fascination with ancient Egypt has a long history; Greek rulers often portrayed themselves as pharaohs and Romans dragged obelisks out of Egypt to adorn their cities, including Istanbul and Rome. Following Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, Egyptomania gripped Europe and amateur archaeologists began flocking to the country, unearthing massive temples and statues and excavating untold numbers of tombs, including the famous tomb of Tutankhamun, discovered by Howard Carter in 1915. But of all the impressive sites and artifacts found, the pyramids of ancient Egypt are unmatched in grandeur.

Pyramids were built as funerary tombs for pharaohs and high-ranking officials from 2600 BCE to 1550 BCE. These massive monuments displayed a person’s power and wealth and served as a place of ascension into the afterlife. Over 100 pyramids have been found in Egypt, mostly in clusters along the west bank of the Nile. The pyramids come in all shapes in sizes, from the early stepped pyramid of Djoser to the uniquely shaped Bent Pyramid, where the pyramid angle was changed mid-way through construction, to the three iconic Pyramids of Giza, which have been dominating Cairo’s horizon since 2550 BCE.

Research on the pyramids have been taking place since the early 19th century, with early archaeologists clearing sand from the complexes and exploring the interior chambers (sometimes, unfortunately, for the pyramid’s preservation, with the help of dynamite) and later archaeologists scanning and restoring the monuments. However, for all the centuries of excavation and research many pyramid mysteries remain.

Pyramid mystery #1: How were the pyramids of Egypt built?

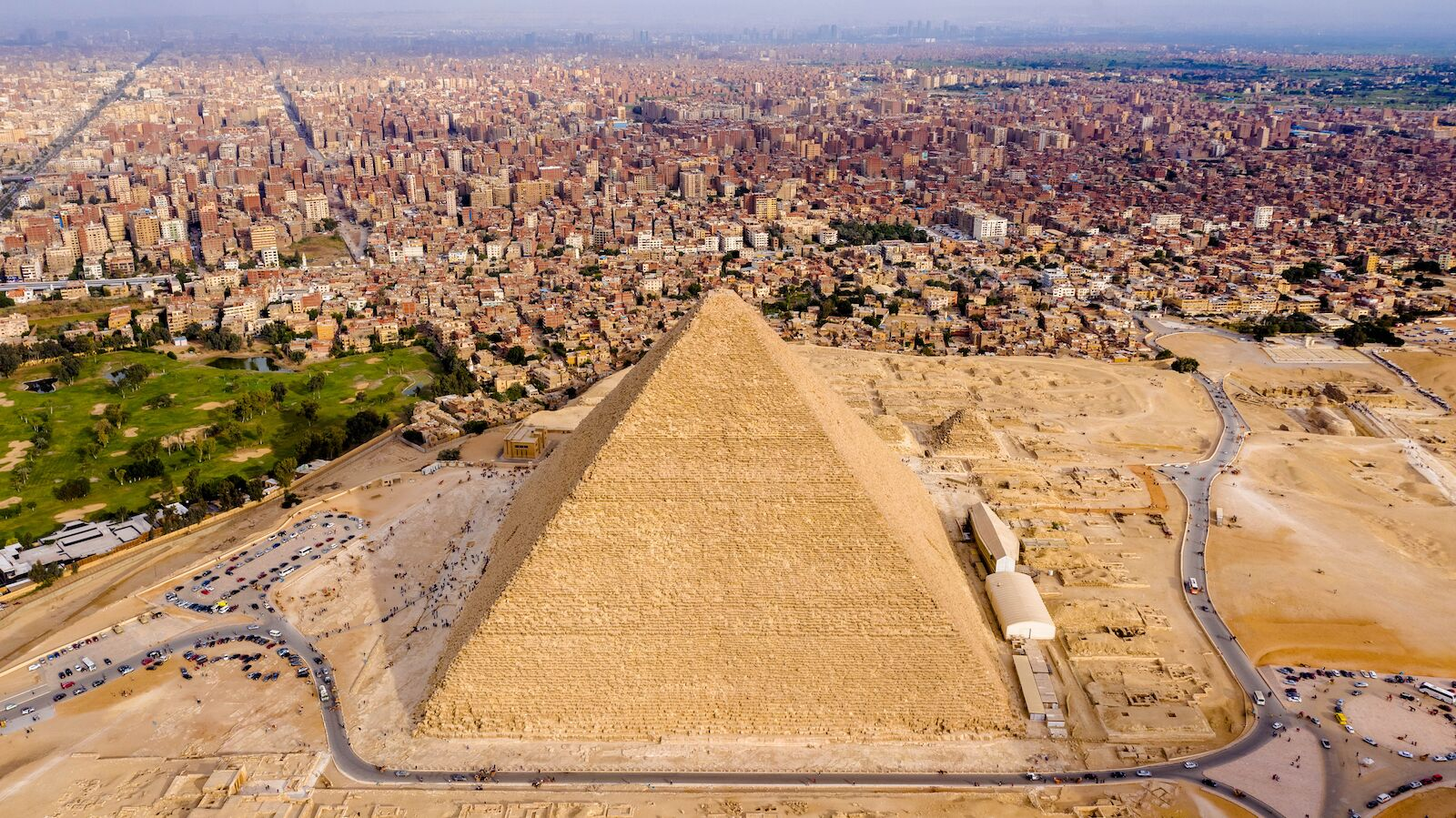

The Pyramid of Khufu. Photo: ImAAm/Shutterstock

The Pyramid of Khufu (sometimes called Cheops), the largest Egyptian pyramid, is made of 2.3 million stone blocks, each weighing anywhere from 2.5 to 16 tons. Some of the blocks, particularly the ones used in the inner chambers, came as far as Aswan, 500 miles from Giza where the pyramid stands. But how did ancient Egyptians build such massive pyramids without using simple machines such as the wheel, which, while used by Egyptians for pottery making, was not used for carts or chariots until 1500 BCE, likely because wheels weren’t much use in the thick sand that covered the country? It’s an age-old mystery and one that continues to be an enigma for ancient monumental complexes across the world. While there are numerous theories, there is a lack of hard, archaeological evidence to fully support any one of them.

One theory about how the blocks were moved involves sleds and wet sand. A painting in the tomb of Djehutihotep shows men dragging a colossal statue on a sled. In front of them, a person pours water onto the sand. While initially thought to be a ceremonial gesture, physicist Daniel Bonn recently discovered that the right amount of water, about two to five percent of the volume of sand, increased the stiffness of the sand and reduced the friction between the object being dragged and the ground, making the object much easier to move. The same technique may have been used to drag stone blocks to pyramid construction sites.

Once the blocks were at the pyramid’s construction site, however, how were they lifted into place without the use of mechanical advantage? A ramp found in a quarry dating to the construction of the Pyramid of Khufu indicates that ancient Egyptians were able to pull stone blocks out of the quarry on a steep upward slope. It’s possible that similar ramps were used to haul stones up the pyramid’s sides to be placed. However, the exact system is unknown. The ramps could have been on the outside of the pyramid, spiraling up like a mountain road, or straight and long, or built within the pyramid. How a 16-ton block could have been moved up a ramp is also unknown, with theories ranging from sleds to wooden rollers to wooden posts tied to each side of a block, changing the shape from square to polygon and allowing them to be rolled like a keg of beer.

Pyramid mystery #2: What’s inside the mysterious cavities inside the Pyramid of Khufu?

In 2017, ScanPyramids made a massive discovery inside the Pyramid of Khufu. With the aid of muon-tomography, a non-invasive scanning technique that uses cosmic rays to produce 3D images of spaces and can penetrate much more deeply than X Rays, researchers discovered two previously unknown voids inside the pyramid, the first new spaces found inside the pyramid since the 19th century.

A small void was detected on the pyramid’s north face, approximately 15 feet long. Horizontal and sloping upwards, this could be a passageway. More significantly, a 100-foot-long void was found above the Grand Gallery, itself a magnificent passageway that provides access to the burial chambers towards the center of the pyramid.

Not much is known about this larger chamber. It could be either horizontal or at a slope and may actually be made up of several smaller rooms. While it is unlikely to be a burial chamber, it could be a second Grand Gallery, or, more intriguingly, hold some of the secrets to the engineering and construction behind the pyramid. The Bent Pyramid, built by Snefru, Khufu’s father, has a similar chamber above the main burial chamber. The space is believed to help reduce the weight of masonry pressing down from above.

ScanPyramids has plans to scan more pyramids, including the Pyramid of Khafre, Egypt’s second largest. What other secrets could muon-tomography reveal about ancient Egypt’s monuments? Time will tell.

Pyramid mystery #3: Why did the Egyptians stop building pyramids?

Photo: Gurgen Bakhshetyan/Shutterstock

The last royal pyramid was built around 1500 BCE. Afterward, while wealthy individuals were occasionally buried in or near pyramids, pharaohs were buried in the Valley of Kings, near Thebes (modern-day Luxor), the new capital of ancient Egypt. What exactly caused the rulers of Egypt to abandon the practice of pyramid burials is unknown, though many theories exist.

One theory is that religious changes around 1500 BCE began emphasizing building tombs underground, in the bedrock, rather than interring bodies in pyramids. Thebes, unlike the previous Egyptian capital, Memphis, had far less open space and what little there was was rocky and rugged, hardly the ideal landscape to build massive monuments.

Tomb robbing was also an issue, and there was far less chance that burials would be looted if they weren’t placed in such conspicuous settings as horizon-dominating pyramids. The Valley of the Kings is a cliffy, complex landscape that was easy to hide royal burials and rock-cut tombs in. Tuthmosis, the first pharaoh to be buried in the Valley of Kings, hired a man named Ineni to inspect the excavation of his tomb. In his autobiography, Tuthmosis wrote, “I inspected the excavation of the cliff tomb of his Majesty alone, no one seeing, no one hearing.” Entrances were kept secret and necropolis guards patrolled the area for looters.

A more recent theory about why pyramid construction stopped comes from Peter James, an engineer tasked with examining the outer casing of the Bent Pyramid, built in 2600 BCE. While better preserved than other pyramids, which all have lost their outer casings of limestone and marble, the Bent Pyramid’s casing has also been breaking apart. Peter James discovered that the extreme temperature fluctuations of the Egyptian desert were causing the limestone to expand and contract, moving the stone blocks to the edges of the pyramid and forcing them to detach or break, taking the outer casing with them. Oddly enough, the Bent Pyramid’s unusual construction made it the best preserved pyramid; the gaps between the stone blocks have allowed them to shift with thermal expansion without breaking the casing. On the other hand, the more perfectly aligned and placed blocks of the Pyramids of Giza had no gaps between them. Any shifting of the blocks caused them to push against each other, causing the casing to disintegrate rapidly. This disintegration likely happened while pyramid building was still occurring. After spending so much time, money, and energy creating perfect monuments, this visible and rapid destruction of their perfection could have been one reason pharaohs abandoned them as burial monuments.